The “Clapper”, literal snail mail, anti-gravity underwear – there are reasons why all of these objects are extinct. But now, a new book is exhuming them from the trash heap of history.

In “Extinct: A Compendium of Obsolete Objects,” a team of professors, historians, artists and curators seeks to understand why various objects became “obsolete,” and what this tells us about the worlds they existed in.

Modern technology now moves at a lightning pace, with endless updates to phones, cameras and other gadgets. But the book’s authors hope to challenge the assumption that things disappear due to “inadequacy” or “unsuitedness to their conditions.” From the defunct to the superseded, from the failed to the visionary, there can be many reasons why an invention no longer serves a purpose.

“Extinct” features a collection of 75 practical, bizarre and often hilarious inventions, many of which shine a light on how our hopes for human progress have evolved.

“When we say that extinction is not inevitable, we shift the ground a little and open up different kinds of histories. These histories are less heroic,” said one of the book’s authors Barbara Penner, a professor of architectural humanities at University College London’s Bartlett School of Architecture.

“A functionalist or overly literal idea of extinction just doesn’t capture the way objects can live on, tucked away in drawers and cupboards and enduring in habit, memory and imagination,” she wrote in an e-mail.

Reframing extinction

The book argues that material extinction happens for many reasons. Some objects simply outlive their purpose when new innovations come along, as was the case with flashcube camera devices (replaced by electronic flashes) and water bags (superseded by more convenient bottles).

However, the reason for an object’s disappearance isn’t always because it was replaced by something shinier and newer. Some are consigned to the past because governments or societies simply deem it time to move on.

Take the incandescent light bulb, which has been actively phased out by American, British and several European governments in recent years due to concerns around energy efficiency. Meanwhile, some nations have started introducing measures to curb the use of plastic bags for environmental reasons, with countries such as Kenya banning them outright and other governments introducing bans or additional charges at supermarkets.

“This category of objects (enforced) is interesting for showing how the fate of a design is often completely intertwined with politics and, again, countering this idea of design failure as ‘natural,’” Penner said.

There are also wildly inventive creations that were, ultimately, architects of their own demise. This was the case with the Chaparral 2J. Nicknamed the “sucker car” or the “vacuum cleaner,” the racing vehicle, unveiled in 1970, became a daring contender on the American motorsport scene. Known for the deafening noise of its engine fans, the car was plagued by mechanical problems. It was banned by the Sports Car Club of America in 1973, condemning it to obsoletion.

Other inventions never really get off the ground to begin with, like the widely mocked “snail telegraph” of the 1850s – a wireless messaging system that gave pairs of letter-assigned snails electric shocks in the misguided belief that the animals became telepathically linked after mating.

Unlike extinction in the natural world, material extinction is typically viewed as a sign of human progress. Objects being superseded into extinction can be a sign of technological innovation, while the phasing out of inventions like arsenic-laced wallpaper (the chemical was used to create vibrant hues) and the leucotome (a rudimentary surgical instrument once used to perform lobotomies) helped save lives after their now-obvious flaws were discovered.

However, the book challenges us to think more carefully about what forces shape progress – like Chinese traditional “dougong” roofs, which were made from interlocking wooden brackets without nails or screws but, the book states, “became defunct in an era of British imperialism.”

“Today, with the climate crisis to take just one example, we are confronting the fact that the newest, shiniest invention is not always the most fit one,” said Penner.

Paving the way for future design

As “Extinct” demonstrates, progress is rarely ever linear. Several of the extinct objects included have been revived in recent years. The Polaroid, for instance, has made a comeback as a new generation falls in love with analog photography as other innovations like the Manchester Pail System, a waste disposal truck, now sit in museums as monuments to their time.

“We weren’t surprised by any single object (nominated by our authors) so much as by the overall pattern that emerged. Many of the nominated objects weren’t truly extinct,” Penner explained, adding that some were still used in different parts of the world, collected or displayed in museums.

And despite disappearing from view, the spirit of certain items pave way for newer designs. Take the Nikini, absorbent underwear designed for menstruation that was created in the late 1950s but, after falling out of use, has re-emerged via brands such as Thinx and Modibodi, which create modern versions for today’s women. Penner also added that shortly after the authors included the Zeppelin, an airship made at the turn of the 20th century, a conceptually similar version was “crowd-funded back to life” on CrowdCube – one that uses helium instead of the highly flammable hydrogen that powered its predecessor.

“We found ourselves confronting the fact that, to enter the world of extinct objects is to enter the world of the undead. Very little expires completely. And, even if functionally extinct, objects very often leave residues: in subsequent designs, language, behavior and habits.”

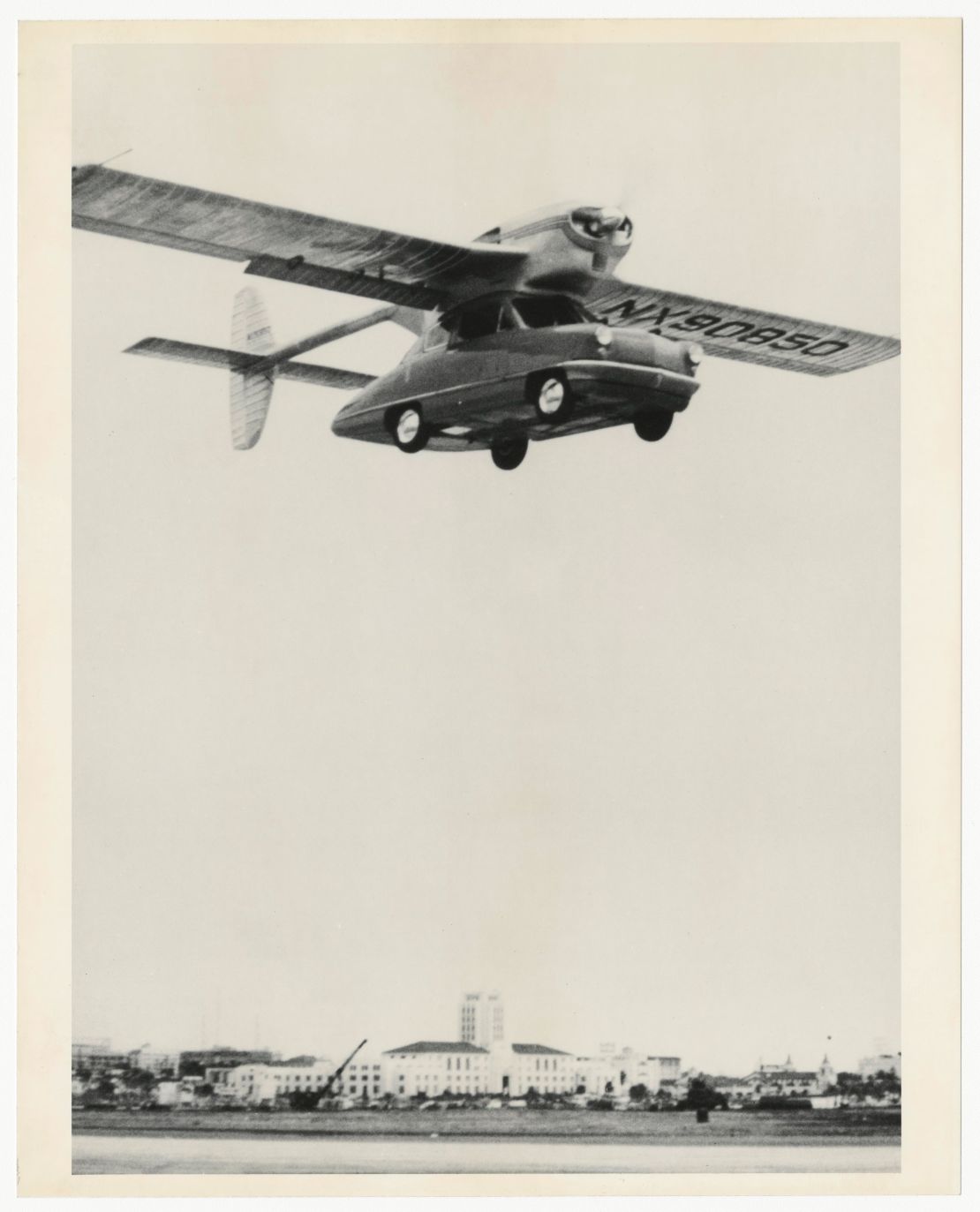

These designs can also remain windows into a specific moment in human innovation. So too do ideas like the ConvAirCar (a flying automobile designed for personal use) or Thomas Edison’s anti-gravitation underwear (underwear which allowed you to fly), which didn’t make it to production but still provide valuable insight into what inventors thought might one day be possible.

“Many of our extinct objects embody other ways of thinking, making, and interacting with the world. They effectively are stores of memories, potential and provocation.”

Top image credit: The Clapper, a popular 2000s light switch that would activate with a loud clap.