Editor’s Note: This article was published in partnership with Artsy, the global platform for discovering and collecting art. The original article can be seen here.

From the 15th century to our current day, the Renaissance maxim holds true: “Every painter paints himself.” Beyond straightforward self-portraits, artists through the ages have left special signatures on their canvases, covertly inserting their own visages into their works in unusual and inventive ways.

This sense of self-importance for the artist arose in the Renaissance with humanist values that prized individualism and creativity. During that era, two trends for hidden self-portraits emerged in Europe. In Italy, artists tended to include their portraits on the right side of paintings or altarpieces, with their eyes looking knowingly out at the viewer. Northern Renaissance artists, however, liked to toy with dense and precise symbolism that showed off their technical skills. The self-portraits they worked into their oil paintings are usually found distorted in reflective surfaces, like mirrors.

The traditions begun in this artistic golden age remained cogent through the modern era and have persisted to this day. Here, we spot eight self-portraits artists concealed in some of their most famous works.

The Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck (1434)

One of the most enigmatic paintings in Western art history is also one of the most fun to look at. Jan van Eyck’s sumptuous wedding portrait revels in painstakingly rendered tokens of wealth and other symbolic details.

Much has been made of the small convex mirror on the wall behind the newlyweds, which shows two additional figures entering the room. The bridegroom raises his arm in an apparent greeting, a gesture that is returned by one of the men in the mirror. Immediately above it is Van Eyck’s flowery signature: “Jan van Eyck was here.” Does the writing suggest that the mirror men are the artist and his assistant visiting his subjects? It’s one of art history’s greatest unsolved mysteries.

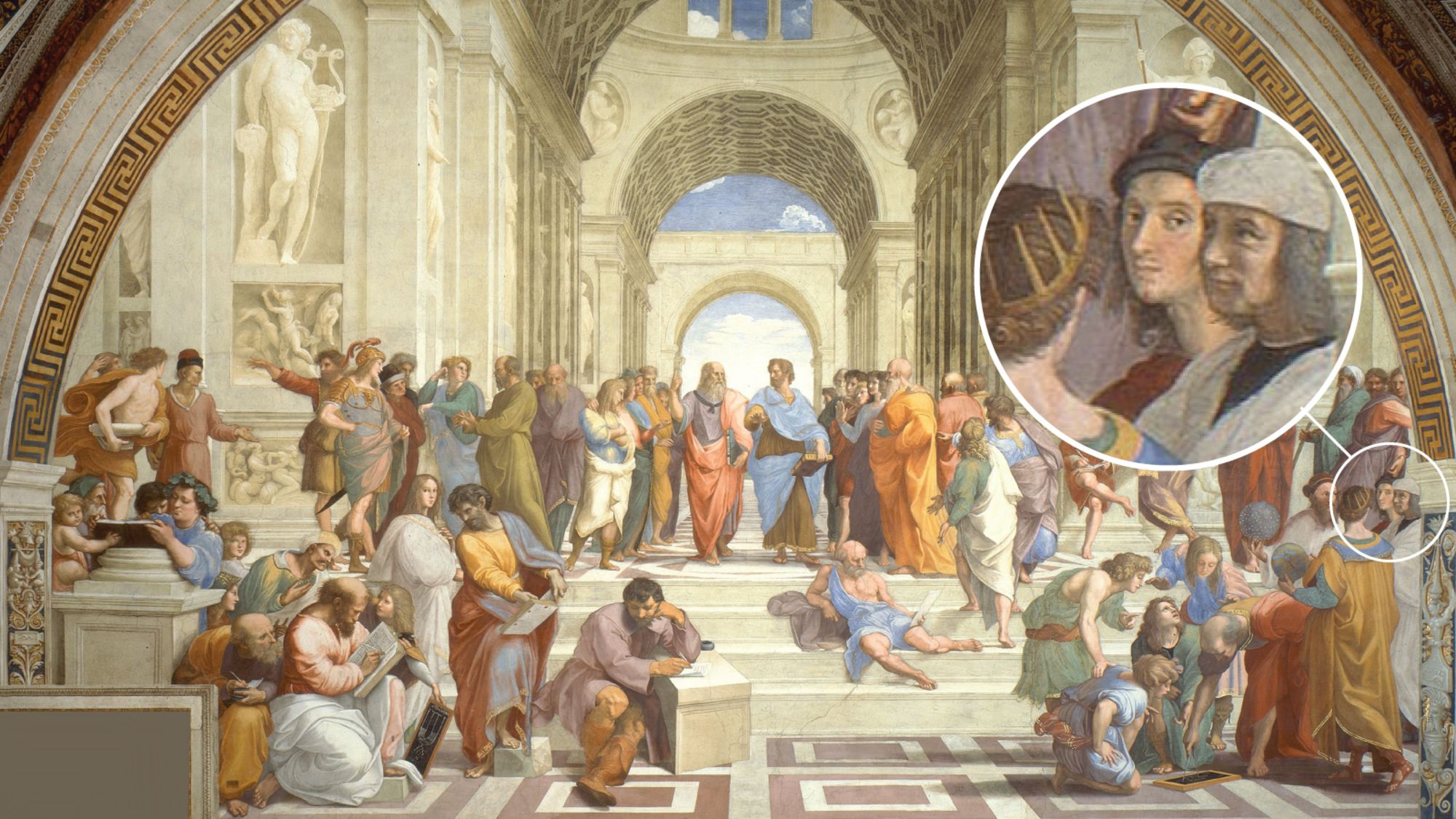

“The School of Athens” by Raphael (1509-11)

Raphael’s famous fresco, painted on the wall of the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace, is considered a masterpiece of Classicism. The scene is a highly ordered paean to philosophy. Scores of revered ancient thinkers – from Pythagoras to Ptolemy – populate a vaulted marble hall with columns and coffered ceilings.

The fresco is a veritable who’s who of Renaissance intellectualism, and Raphael conflated his own era with the vaunted past. According to fellow Italian painter Giorgio Vasari, Raphael depicted his contemporaries in the scene as the philosophers. Bramante, bent over a chalkboard, is Euclid or Archimedes; Leonardo da Vinci is thought to be the model for Plato; and Michelangelo may be the face of Heraclitus. The artist couldn’t resist including his own face in the mix: Raphael’s curious face peeks out from behind the arch on the far right of the fresco, beside Ptolemy and Zoroaster.

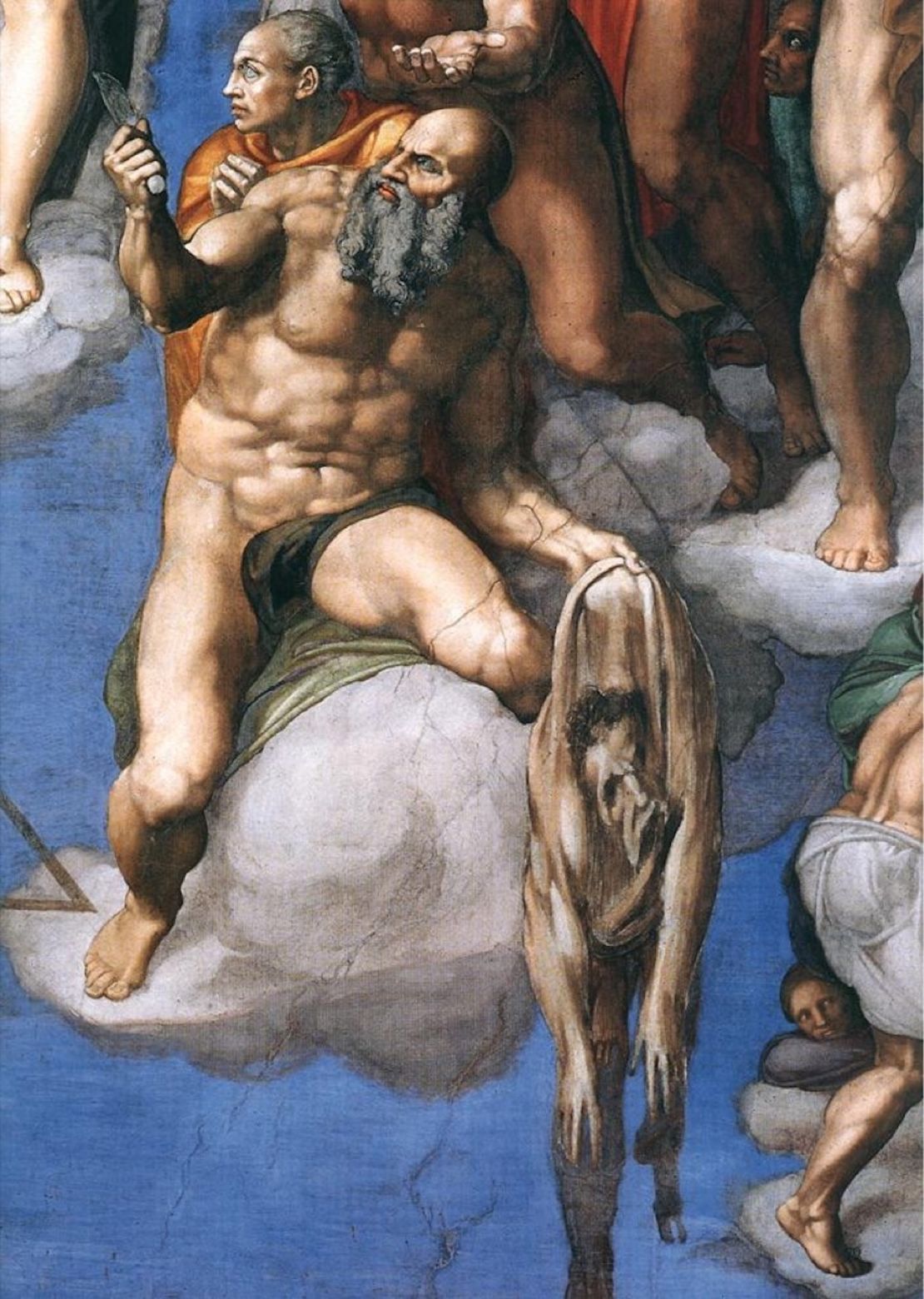

“The Last Judgment” by Michelangelo (ca. 1536-41)

It’s common knowledge that Michelangelo loathed the commission to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling in the Vatican. In a poem written for a friend in 1509, the tempestuous artist griped about the long hours laying on his back: “My brush, above me all the time, dribbles paint so my face makes a fine floor for droppings!”

In the end, the Renaissance master was able to cleverly express his frustration – and have some fun at the pope’s expense – when he took on the “Last Judgment” fresco for the altar wall of the chapel. In the center of the expansive painting, Michelangelo’s horridly eyeless face sags, an empty suit of flagellated skin, from Saint Bartholomew’s hand. The Renaissance master imposed himself on the martyred saint, who is waiting to discover if he is off to heaven or hell after a grueling trial of faith.

“David with the Head of Goliath” by Caravaggio (1609-10)

Before his untimely death at age 38, Caravaggio painted himself in many guises, most frequently as the Greek god of wine, Bacchus. In the last year of his life, he decided to include a self-portrait in a depiction of the victorious David proffering Goliath’s severed head – one of several versions Caravaggio made of the biblical story. This iteration offers an unexpected level of emotional nuance to a usually gory, black-and-white tale of “might vs. right.”

Here, Caravaggio is not the youthful, good-looking David, but the defeated Goliath, his slack-jaw mouth confirming his slaughter. Instead of a look of satisfied victory on his face, David appears pensive and a bit mournful, perhaps even regretful, as he gazes at his prize. Scholars have surmised that the model for the young hero was Cecco, Caravaggio’s studio assistant and purported lover. The painting, then, has an unexpected psychosexual intimacy to it, one that is reiterated by David’s sword, standing suggestively erect between his legs.

“Still Life with Cheeses, Almonds and Pretzels” by Clara Peeters (ca. 1615)

Dutch still lifes seem straightforward, but often suggest complex meditations on mortality. While the technical difficulty of the genre and its intellectual conceits might have presented a barrier to access for female artists, women in the 17th century thrived in the genre. Clara Peeters was among the most talented still-life artists of her day.

Many Dutch artists of the era painted lavish arrangements with oysters, mince pies and imported fruits and peppercorns on silver and gold plates, but Peeters favored humble displays of native dairy products like cheese and butter with peasant bread. Yet she couldn’t resist showing off her painting chops in one still life featuring an array of cheeses, almonds and elegantly twisted pretzels. In the reflection of the ceramic goblet’s pewter lid, Peeters carefully rendered her self-portrait, accurately distorted by the curve of the object. In lieu of a signature, the artist “carved” her name into the silver butter knife.

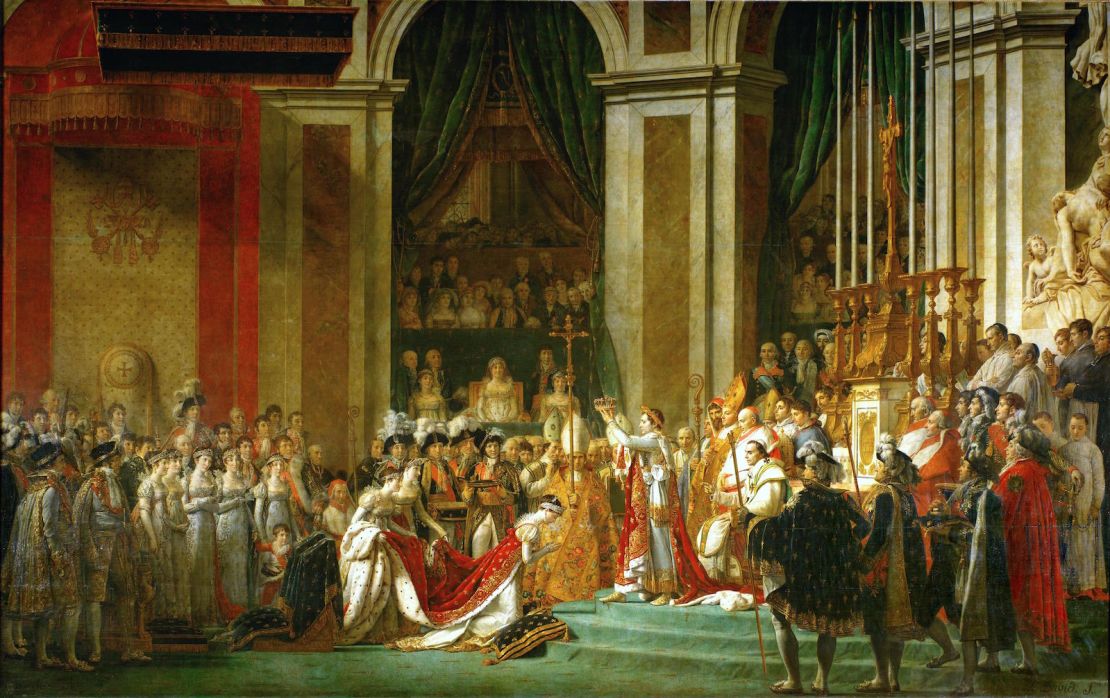

“The Coronation of the Emperor Napoleon I and the Crowning of the Empress Joséphine in Notre-Dame Cathedral on December 2, 1804” by Jacques-Louis David (1806-07)

The French Neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David is an interesting figure in the history of revolutionary France. Despite his role in overthrowing the monarchy, after the war, David cannily pledged allegiance to Napoleon, becoming the emperor’s royal painter and master propagandist.

Napoleon himself commissioned David to record his opulent 1804 coronation in a monumental history painting that conveys a strong political message of power. Today, the artwork dominates the Louvre’s Great Hall. It’s so massive that its subjects appear life-size; viewers might feel as if they were among the colorfully painted crowd, observing Napoleon crowning Josephine

David himself sits in the elevated theater box in the center of the composition, sketching the scene amid the velvet-, fur- and satin-clad members of the imperial family and other aristocrats. In reality, the artist was present at the actual coronation ceremony at Notre-Dame. His inclusion in the painted version of events shows the artist’s allegiance to the crown, and nods to his undeniable tour-de-force artistic achievement.

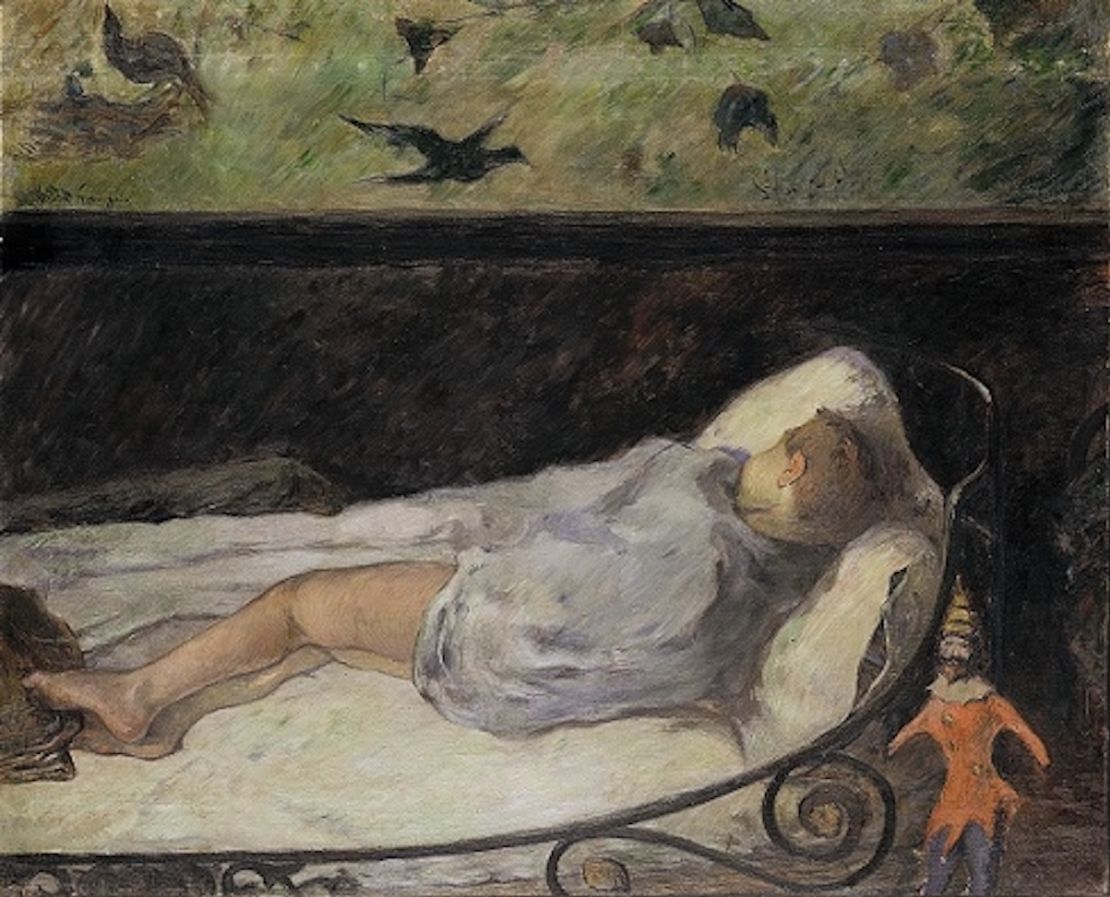

“The Little One Is Dreaming, Étude,” by Paul Gauguin (1881)

It wasn’t unusual for modern and Impressionist artists to include themselves in their paintings; they often inhabited their own scenes of Parisian cafes, bars and parks. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, to name one example, depicted himself in the background of “Au Moulin Rouge” (1892-95), one of his favorite haunts.

But Paul Gauguin took a stranger approach to self-portraiture in “The Little One Is Dreaming, Étude.” As a child lays sleeping, a creepy jester doll stands, a little too animated, beside the crib. Look closely at its face and notice the fool is Gauguin. The artist may have intended the toy to be a figment of the child’s dream. If that’s the case, he’s more nightmare than fantasy.

“Swimmers in the Lap Lane,” by Nicole Eisenman (1995)

In crowded paintings of beer gardens and house parties that remix art-historical styles, Nicole Eisenman resurrects the sociable leisure scenes favored by modern artists of the 19th and 20th centuries for the contemporary age.

Eisenman herself rarely makes an appearance in her work, though her friends and lovers often populate scenes. An early painting by the artist, however, provides a typically humorous yet vulnerable self-portrait. The frenetic composition features a mélange of nude swimmers lashing about the lap lanes, frantically groping at one another in an unusually sexual take on a swimming pool scene. On the bottom right side of the work, Eisenman, mid-backstroke and wearing nothing but goggles and a swim cap, gasps for air. It’s funny and frightening and hot, all at once – characteristics that seem essential to her work to come.