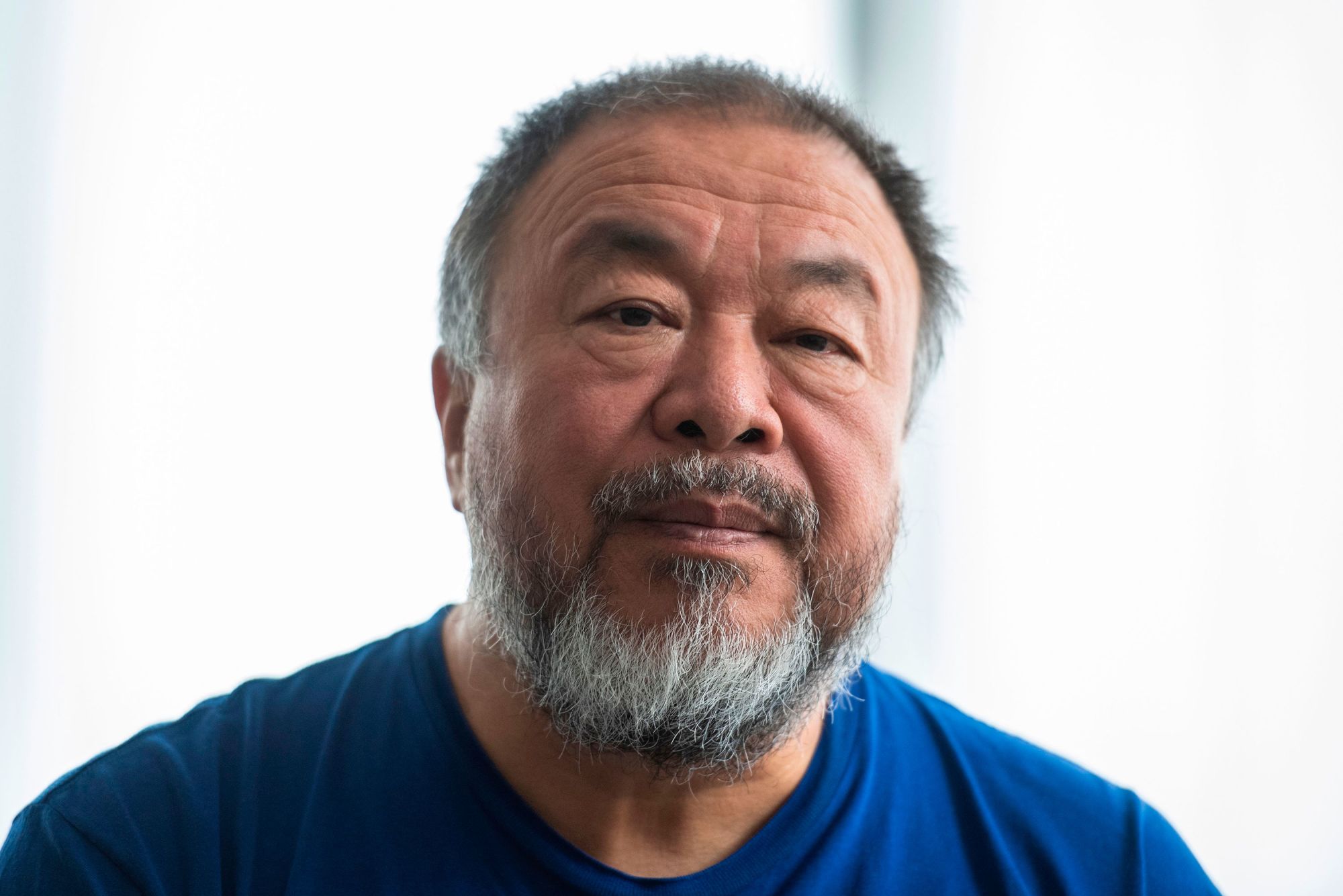

As the world grapples with unprecedented lockdown measures, Ai Weiwei finds himself in familiar territory. The outspoken artist spent nearly three months in a tiny room while detained by authorities in China in 2011.

He was later accused of tax evasion, a charge widely interpreted as punishment for his political activism. Following his release, Ai’s passport was confiscated, and he was placed under close surveillance in Beijing.

In Cambridge, England, where the 62-year-old dissident now resides, self-isolation has stirred similar feelings of solitude. “You (feel) disassociated, you’re dysfunctioning and you’re uncertain about your own future … you’re trying to imagine behaving in relation to others,” he said, over the phone, of restrictions implemented to contain the coronavirus.

Ai has been critical of China’s handling of the outbreak, which was first identified in the city of Wuhan and has since spread to more than 210 countries and territories, infecting over 2.5 million people. In a recent opinion piece for The Art Newspaper, he argued that the ruling Communist Party’s containment tactics have proven the “effectiveness of authoritarian rules,” while other countries’ inability to control the pandemic has exposed the “disadvantages and malpractices of free and democratic societies.”

Such comments are consistent with his wider assessment of the Chinese state’s far-reaching powers. Many issues raised by the pandemic, from censorship to surveillance, are subjects Ai has spent years exploring.

Controlling the narrative

In recent weeks, much has been made of China’s alleged efforts to conceal the initial outbreak of the virus – an allegation Beijing strongly denies.

According to Ai, China’s selective handing of information early on provided a “chance for the virus to spread.” However, understanding China’s motivations is as important to Ai as the alleged cover-up, or the suggestion that the country’s infection numbers and fatalities have been under-reported.

“The West’s blame is very superficial,” said Ai. “They (in the West) only talk about China practically – (that it) doesn’t release information. But they never ask, ‘Why?’”

As Ai sees it, China would not function as a state without the “control and manipulation” of information.

“For China, everything is for political use. And they have a clear reason to give the numbers they want to, or to limit or to change or distort the so-called truth,” said Ai.

“A number means nothing to them,” he said, adding that there’s little recognition of the individuals and “deep souls” making up the death toll. “In many cases in China, you don’t even get the real names or how many people. They are completely lost because the state wants (to preserve) its own image.”

Questioning official accounts is hardly new ground for Ai. Following the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, which is believed to have killed almost 90,000 people in western China, Ai set up a team to identify its youngest victims by meeting with their parents and recording their names, birth dates and the schools they attended – information the government had attempted to censor.

At least 5,000 children were killed, many of them crushed under the weight of shoddy school buildings. In his 2009 artwork “Remembering,” Ai arranged 9,000 student’s backpacks to read, “All I want is to let the world remember she had been living happily for seven years,” a line from a letter written to him by a victim’s mother.

According to Ai, history is destined to repeat itself in China if the government won’t admit to past mistakes.

“China will never learn. It doesn’t matter what kind of disaster they’re facing. The only thing they learn is how well they use this authoritarian power to manipulate the story. That kind of arrogance and success will lead them to another crisis.

“It’s a pity. It’s obvious they have to change their behavior and to learn to be more scientific and trust their own people, but simply, there is no trust in China between the leaders and their own people, between people themselves, and between individuals’ understanding of the current situation and (their) own future.”

Maintaining state control may have just been made far easier. During the pandemic, China’s authorities developed a color-based “health code” system designed to track people’s movements and curb the spread of the virus. Using mobile technology and big data, unique digital QR codes were assigned to hundreds of millions of citizens, indicating their health status and giving them access to (or barring them from) public transportation, restaurants and shopping malls.

As a result, Ai believes the virus has only strengthened what he calls the “police state,” allowing the government to continue to harvest data and build a deeper understanding of its citizens. “China has 1.4 billion people and one single power. They have to actually maintain this kind of power by knowing everybody – what’s on their mind, and their behavior.”

Creating art

Ai began monitoring the virus’ initial outbreak in Wuhan – where a number of his relatives and friends live – back in January, working remotely with local crews to film what was happening on the ground and in hospitals.

Those were his nights. His days were spent directing dress rehearsals of Puccini’s “Turandot” for Rome’s opera house, the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma. Ai’s interpretation of the early-20th-century libretto already drew on contemporary topics close to his heart: the global refugee crisis and Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests. The Covid-19 crisis was a late addition – a full stage of actors were set to appear in the last scene dressed in medical garments.

He initially questioned the idea, wondering whether references to the virus “would make sense.”

Turns out, it was prescient. The production’s opening night was postponed just a few weeks out, as the number of cases exploded in Italy in early March. “I was shocked,” he said. “Not because we had to stop the opera, but because my artwork, which I had been preparing for over a year, had clashed with reality.”

That reality has since become increasingly bleak, with the virus’ global death toll rising to over 177,000. Many of those deaths are experienced alone, in hospital isolation wards away from family members or friends.

The idea that so many people are absent for the “last glimpse or last sentence of their loved ones before they leave this planet,” deeply saddens the artist.

“I am just like another person, totally lost,” he said. He’s measured about art’s role during this time.

“Even in terms of good writing, philosophical thinking, or a good image cannot really compare or cope with the deep sorrow, the sadness and the disappointment of our current situation, or even our understanding about the future.”

So, for now, he’s keeping busy by planning documentaries, writing out arguments and conducting interviews. And, on occasion, “the form will come out” – like on a recent walk in Cambridge, when he found a log laying on a patch of grass.

He carried it home and, together with his son, carved out a wooden roll of toilet paper.