Wealthy business entities and conservative advocates have been building toward this Supreme Court moment for decades. And now with three appointees of former President Donald Trump on the bench, their goal appears within reach, and the regulatory world could be turned on its head.

Justices who’ve been gradually constraining federal regulators sounded ready during arguments on Wednesday to make their most substantial move yet and gut a 1984 ruling that has given US agencies wide latitude over policy, from environmental protection to workplace safety.

Reversal of the so-called Chevron deference approach was a priority for the judicial selection team that served Trump – on par with some right-wing activists’ quest for reversal of constitutional abortion rights. The reconstituted Supreme Court delivered on that agenda item in 2022 when it overturned Roe v. Wade.

Former White House counsel Don McGahn, who controlled Trump’s judicial selections, regularly touted the administration’s anti-regulation agenda. He was especially drawn to the first two Trump appointees, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, for their records in that regard.

“There’s a coherent plan here, where actually the judicial selection and the deregulatory effort are really the flip side of the same coin,” McGahn said at a 2018 appearance.

McGahn also remarked publicly of Gorsuch’s personal history. The Chevron case traces to the early 1980s tenure of Anne Gorsuch, then the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, who cut back on air and water quality initiatives in the Reagan era of deregulation.

“Unlike Justice Gorsuch, my mother was not the head of the EPA,” he told a law school audience in 2020, but added, “I’ve always had an aversion to concentrated power.”

The Trump administration’s disdain for the so-called administrative state was shared by two other key players in its judicial project: Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell, who sped candidates through the Senate during Trump’s four years, and Leonard Leo, a Federalist Society leader who has raised and channeled millions of dollars to conservative social causes and big business initiatives.

Business groups have argued that the Chevron principle requiring judges generally to defer to agency interpretations of their statutory mandates has led to an uncontrolled bureaucracy that inevitably, and unfairly, gets the upper hand in litigation. The Biden administration, backed by public health, labor and environmental advocates in the current cases, has stressed agency expertise and the value of uniform, nationwide rules overseen by executive-branch agencies.

Gorsuch and Roberts leave no doubt

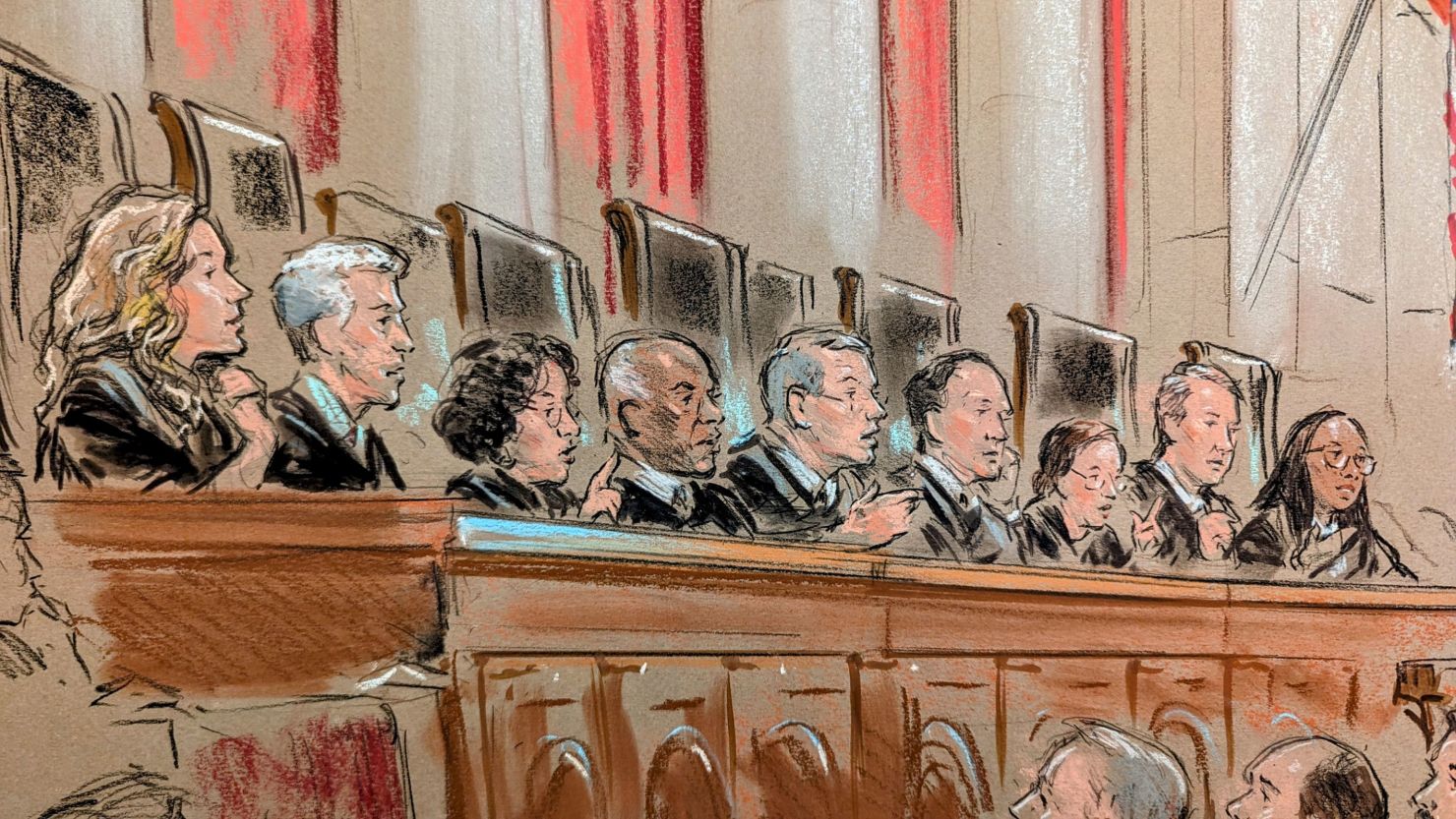

During more than three hours of fast-paced arguments Wednesday, the conservative majority was largely in lockstep against the 1984 ruling of Chevron USA, Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council.

“The government always wins,” Justice Gorsuch remarked. “Chevron is exploited against the individual and in favor of the government.”

Chief Justice John Roberts suggested by his questions that he believed the high court’s recent pattern had already signaled to litigants the demise of Chevron.

“How much of an actual question on the ground is this?” Roberts asked lawyer Roman Martinez, representing one of the two Atlantic herring fisheries that challenged National Marine Fisheries Service rules at the center of the case. Roberts noted that the justices have regularly rejected the Chevron framework, which dictates that when disputes arise over an ambiguous law, judges should defer to agency interpretations, as long as the interpretations are reasonable.

Martinez said US lower courts across the country still follow the 1984 precedent, and that is why judges had declared – wrongly in his view – that a federal law, the Magnuson-Stevens Conservation and Management Act, gave the National Marine Fisheries Service the authority to require vessels to carry at-sea monitors and to bear the costs.

US Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, urging the justices to uphold the lower courts and retain the 1984 milestone, told the justices, “The Chevron framework is a bedrock principle of administrative law with deep roots in this court’s jurisprudence.”

“Overruling a precedent is never a small matter, but overruling a precedent as foundational as Chevron should require a truly extraordinary justification, and (the challengers) don’t have one,” Prelogar added. “Thousands of judicial decisions sustaining an agency’s rulemaking or adjudication as reasonable would be open to challenge.”

Will courts be left as the ultimate decider of health care and AI?

With the momentum against the Chevron principle palpable in the courtroom, liberal justices highlighted the potential consequences of disregarding agency expertise.

“Is a new product designed to promote healthy cholesterol levels a dietary supplement or a drug?” Justice Elena Kagan asked Martinez, observing that the query would come down to the interpretation of statutory terms. “You think a court should determine whether this new product is a dietary supplement or a drug without giving deference to the agency? … You want the courts to decide that?”

Kagan offered several hypothetical scenarios that reflected the many ways the Chevron case, among the most cited Supreme Court precedent on the books, affects government mandates and benefits.

Congress routinely writes open-ended, ambiguous laws that leave policy details to agency officials. If Chevron is reversed, judges would have greater influence over the policy implications.

“So let’s imagine Congress enacts an artificial-intelligence bill and it has all kinds of delegations,” Kagan continued. “And then, just by the nature of things and especially the nature of the subject, there are going to be all kinds of places where, although there’s not an explicit delegation, Congress has in effect left a gap. It has created an ambiguity. And what Congress is thinking is, do we want courts to fill that gap, or do we want an agency to fill that gap?”

Martinez said authority should go to the judiciary: “Congress wants the court to do its ordinary function, which is interpret the law and … apply the best understanding of the law.”

A key argument of his and that of lawyer Paul Clement, a former US solicitor general who separately argued for overturning Chevron on Wednesday, is that the case allows agencies to usurp the role of judges. In his written brief and during arguments, Martinez invoked an adage of Chief Justice Roberts from his 2005 confirmation hearings, that judges serve as umpires, just calling balls and strikes.

When liberal Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson suggested that eliminating Chevron deference would turn judges into policymakers, Martinez said, “Judges are not there to exercise force or will. They’re there to exercise judgment. They’re serving as neutral umpires. They’re not players on the field.”

Kavanaugh similarly seized on the judicial role: “Concern for any judge is abdication to the executive branch running roughshod over limits established in the Constitution or, in this case, by Congress.”

Kavanaugh, once an administration lawyer himself (during the George W. Bush tenure), took issue with Prelogar’s contention that reversal of Chevron would be “an unwarranted shock to the legal system.”

Said Kavanaugh, “The reality of how this works is Chevron itself ushers in shocks to the system every four or eight years when a new administration comes in.”