If you don’t realize how powerful White Christian evangelicals have become, consider this:

A White Christian evangelical, who has been described as “the embodiment of White Christian nationalism in a tailored suit,” is now second in line to the presidency.

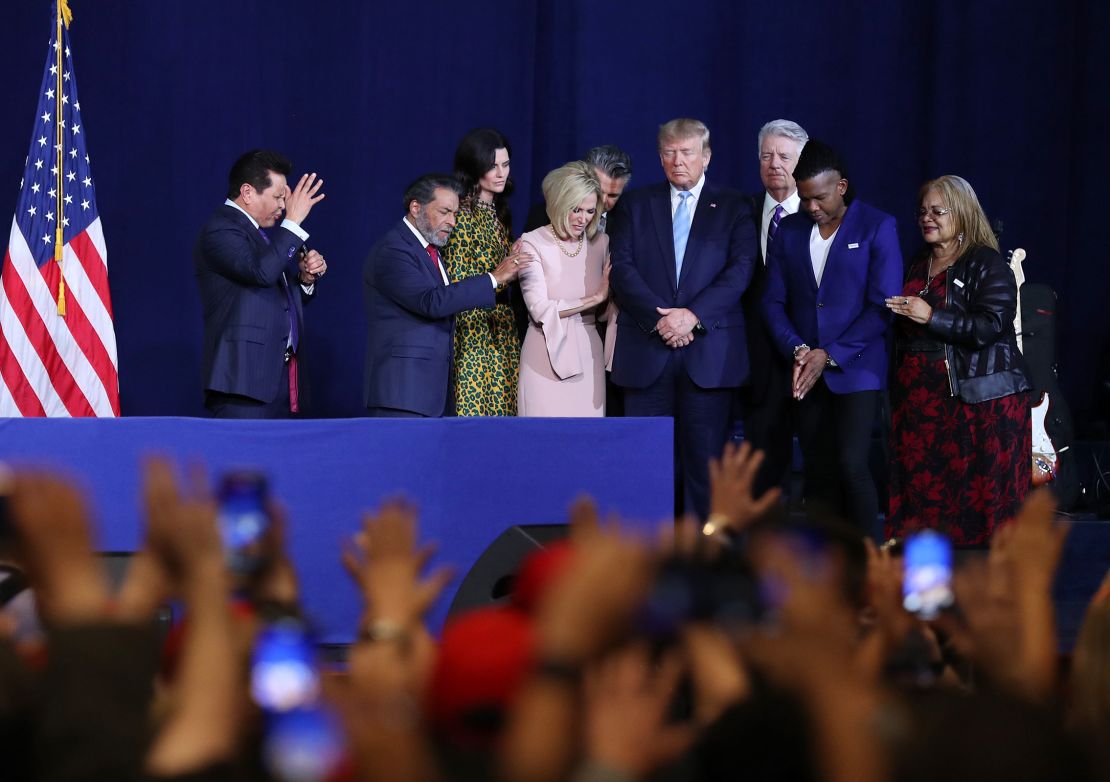

Rep. Mike Johnson, the new Speaker of the House, is a White evangelical. His ascension represents one of the greatest political ironies of our time. White evangelical Protestants make up only about 14% of Americans, and that number has been steadily shrinking. But White evangelicals have amassed more political power than ever. They helped inspire the US Supreme Court to overturn Roe v. Wade last year, and their steadfast support of former President Trump could return him to the White House.

Yet there is still widespread misunderstanding of White evangelical subculture. The media tends to depict White evangelicals as foaming-at-the-mouth Christian insurrectionists like some of those who stormed the US Capitol on January 6, 2021.

One former evangelical, though, has done something rare: He’s written a new memoir that illustrates how White evangelicals were led astray by their thirst for political power but also depicts many of them as earnest spiritual strivers who still retain “immense power for good.”

The book is titled “Testimony: Inside the Evangelical Movement That Failed a Generation,” and it’s by Jon Ward, the chief national correspondent at Yahoo! News. Ward describes being raised in a Christian bubble where watching secular television shows like “Sesame Street” was forbidden. He attended churches where people were “slain in the spirit” while singing songs with choruses such as, “all of us deserve to die.”

The son of a pastor, Ward would go on to become a White House reporter, traveling the world on Air Force One with former Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama. Ward recounts in his brutally honest memoir how his family, like others, were torn apart by the rise of Donald Trump.

“I felt abandoned by my own father,” he writes about his dad, who led an influential evangelical church and who he declines to name in the book. He and his father had argued about Trump describing the media as “the enemy of the people,” Ward said.

“But it helped me understand how good people could stand by and make excuses for bad people in power,” he wrote. “They couldn’t not see past their own resentments and bias, even when people they loved were hurting or scared.”

CNN talked to Ward about why he thinks White evangelicals remain misunderstood, why he’ s leery of using the term “Christian nationalist,” and what it would take for White evangelicals to abandon Trump. Ward’s remarks were edited for brevity and clarity.

The new speaker of the house is a White Christian evangelical and is second in the line for the presidency. Does this inspire or concern you? Or maybe a bit of both?

I think that with his (Johnson’s) sort of surprise ascent into such a position of power so close to the presidency, there’s a lot more attention now on the kind of conservative Christian beliefs that have been common among millions of evangelicals for decades. What’s unusual about Johnson is that while his views are fairly common, it’s uncommon to have somebody get so high in a position of power with his views because usually they have to go through much more vetting. His views about America being a Christian nation are a pretty telling marker of what a lot of experts call “Christian nationalism.”

That’s a term that gets thrown around a lot. I’m wary of using it because I think it’s used as a caricature. There are people who are trying to weaponize Christian nationalism. And I don’t think that that’s most evangelicals. I think it’s people who are associated with the former president’s attempt to overturn the last election. These beliefs have been common for a long time. But this at this moment, they’re merging with a strain of anti-democratic apocalyptic forms of Christianity that have already shown a willingness to throw out respect for the Constitution and democracy.

I think most evangelicals probably have a mix of views. And one of them is that America is a Christian nation, and they don’t have a lot of implications that flow out from that. When you categorize everybody as an extremist just because they hold these views, I think it pushes more evangelicals towards the bad actors who are trying to bring people into an anti-democratic movement.

You seem leery of using the term ‘White Christian nationalism.’ Am I correct?

Yeah, because first of all, most people don’t call themselves Christian nationalists. When you call somebody something that they say, ‘Hey, I’m not one of those,’ I think that’s not great. In many cases, it’s just going to make people more defensive and turn them off and push them away from you. And secondly, there are fully built-out forms of Christian nationalism. But in many cases, it’s just a very amorphous thing. I think many of them are just normal patriotic Americans.

And again, there are a small group of extremists who want to use these ideas to drag people into an anti-democratic movement. And I think the more you sort of say to people, “You’re one of them,” I think the more you leave them little room, and you’re pushing them towards those extremists.

Christian nationalism is not actually faithful to Christianity. In churches, pastors, they’re the ones who are going to be crucial to pushing back against the forces of extremism because they’re the ones who need to speak to their neighbors, friends and church members about the idea that America is a Christian nation is actually not faithful to historic Christianity.

You tell a story about a former colleague in the fall of 2016 who emailed you saying he was alarmed to see Christian evangelical leaders endorsing Trump. And then he became one of Trump’s most ferocious defenders. Why did he and others make a similar shift?

I don’t know what was in their motivation or their hearts. I think a lot of people in those early days of the Trump presidency were known as anti-anti-Trump. They might have been anti-Trump at first, but then they got fed up with the criticism of Trump and the backlash against Trump. And they’re like, I’m now done being anti-Trump. I’m anti-anti Trump. And so that was part of it. I think that was in large part a rationalization for getting to where their audiences were. When your audience wants more pro-Trump stuff, that often ends up leading people around by the nose.

You’ve said, ‘I still believe in evangelicals, but I don’t believe in evangelism.’ What does that mean?

It means that there’s a lot of really great people in these evangelical churches, all over the country and in the world. Just fantastic individuals and families. But there’s a whole culture of political beliefs and cultural practices that have been added on to the faith that I was indoctrinated in. It’s taken me decades to unpack all the assumptions that were layered on to my worldview by these teachings.

You say you were taught what to feel, what to believe, but not how to think. Can you elaborate?

When you’re in that kind of place where all the answers to life’s questions start with a very firm set of beliefs that are based on a text that is interpreted and read in a way that is actually not even the way that the Bible has been read for most of Christianity’s history, then you’re backed into a corner when it comes to asking questions. You can ask them up to a certain point. But once you bump up against any of the answers that are set in stone, the answers start to become labeled as dangerous, sinful, or evil.

What shifted your beliefs from the way you were raised?

If I had to put it on one thing, it would be given the permission to ask questions and follow the truth wherever the facts lead.

Who or what gave you that permission?

Becoming a journalist.

Are you still an evangelical, or do you call yourself something else?

I don’t think I would use that label. I think I would just call myself a Christian.

Is there anything that could cause former President Trump to lose the allegiance of the White evangelicals who support him?

I think it would have to be something more pragmatic and political than theological or moral. If it got down to him versus Nikki Haley (the former South Carolina governor and 2023 Republican presidential contender), and it was clear in the polling that Trump would lose to a Democrat and Haley would beat the Democrat, many evangelicals would switch their support to Haley because they would want a Republican to win the presidency. People are often looking for some revelation that’s going to get people to stop supporting him (Trump) but I think we’re beyond that in most cases.

If Trump wins a second term, what will the impact be on the White evangelical world?

You would see adulation from a lot of evangelicals. You would see a minority of evangelicals peeling away not just from Trump, and not just from Republican politics, but away from evangelicalism. But that’s probably the minority. The word “evangelical” has become more and more wobbly over the last decade because the Trump movement has been able to bring in a lot of people to this style of fusing religion and politics. That attracts a lot of people who are not even really churchgoers.

How has your father reacted to your book?

We spent several hours one day talking about it. He expressed some positive feelings about parts of the book, but his overwhelming response was negative. It may have been a surprise, the level of disagreement that I have with him. It has to be really hard for your son to write anything that’s not praising you.

I went back to him later and I walked him through every moment in the book that he’s mentioned and pointed out that 75% of those mentions are very positive. I was grateful for his love and for his place in my life and for the person he is. Through our conversations, we’ve come to a better place.

Time will tell whether that holds, I guess. It was good for us to talk it out rather than let a lot of stuff fester.

John Blake is the author of “More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew.”