Editor’s Note: Peter Bergen is CNN’s national security analyst, a vice president at New America, a professor of practice at Arizona State University, and the host of the Audible podcast “In the Room with Peter Bergen,” also on Apple and Spotify. Laura Tillman is a producer of the podcast. The opinions expressed in this commentary are their own. View more opinion at CNN.

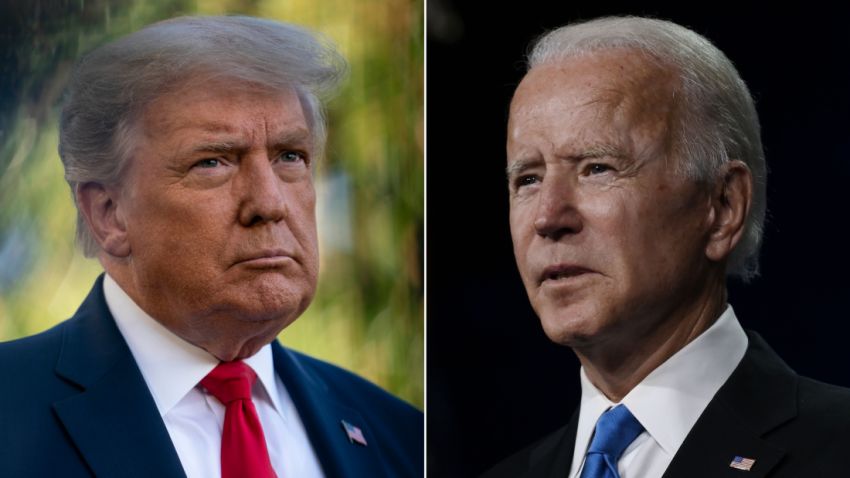

In May 2018, then-President Donald Trump canceled the agreement with Iran to restrain its nuclear weapons program, saying “the Iran deal was one of the worst and most one-sided transactions the United States has ever entered into.”

In fact, the Iran deal was substantially reining in the Iranian nuclear program, according to US intelligence agencies and the International Atomic Energy Agency.

And oddly enough, Trump soon entered into negotiations for what would become, in reality, one of America’s most one-sided and self-defeating deals: the agreement with the Taliban to withdraw all US troops from Afghanistan.

Retired US Gen. David Petraeus, who formerly commanded US troops in Afghanistan, told us in an interview for the Audible podcast, “In the Room with Peter Bergen,” that the deal with the Taliban “ranks with the worst diplomatic agreements in our history. We gave the Taliban what they wanted: We’re leaving. The only thing we got in return was a promise they wouldn’t attack us on the way out.”

President Joe Biden became the second successive president to botch Afghanistan policy when he went ahead and carried out the deal Trump’s team negotiated, leading to the disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan two years ago.

On August 15, 2021, the Taliban marched into Afghanistan’s capital, Kabul. Since then, they have banned women from jobs and have not allowed girls over the age of 12 to return to school. Afghanistan is the only country in the world that has suspended girls from school and women from universities.

The Taliban have also provided safe haven to around 20 terrorist groups, including al-Qaeda, according to a UN report that was released two months ago. As the US military rushed for the exits in the summer of 2021, 70,000 armored vehicles and more than 100 helicopters were left behind, an arsenal worth an estimated $8.5 billion, according to the UN.

Why did Trump and Biden make those mistakes?

Two years ago, the Trump team negotiated the complete US withdrawal from Afghanistan that gave the Taliban the total victory they could never win on the battlefield, while the Biden team went through with this deeply flawed plan.

That withdrawal ended in the hasty retreat of US forces and the chaotic scenes of thousands of desperate Afghans trying to get on flights out of Kabul Airport in August 2021. Televised scenes of the chaos at the airport make the fall of Saigon at the end of the Vietnam War look like a dignified exit.

Lisa Curtis was the top official working at the White House on Afghanistan during the Trump administration. In an interview for the Audible podcast, Curtis told us that the US officials who negotiated with the Taliban, beginning in early 2019, gave the Taliban pretty much everything they wanted and got very little in return. The Taliban committed to breaking with al-Qaeda and entering into genuine power-sharing talks with the elected Afghan government, but neither happened.

Curtis explained that Trump never really was concerned about the details of the negotiations with the Taliban, saying, “I don’t think he cared about a peace deal. He cared about getting US troops out.” The Taliban were no doubt also aware that Trump had long criticized US involvement in Afghanistan; for instance, Trump tweeted in 2013, “Let’s get out of Afghanistan. Our troops are being killed by the Afghanis we train and we waste billions there. Nonsense! Rebuild the USA.”

Trump always prided himself on his purported “Art of the Deal,” but his administration’s negotiations with the Taliban were more like a clueless customer shopping for a car who tells the salesman, “I’ll pay the full sticker price,” as a way of beginning the negotiation.

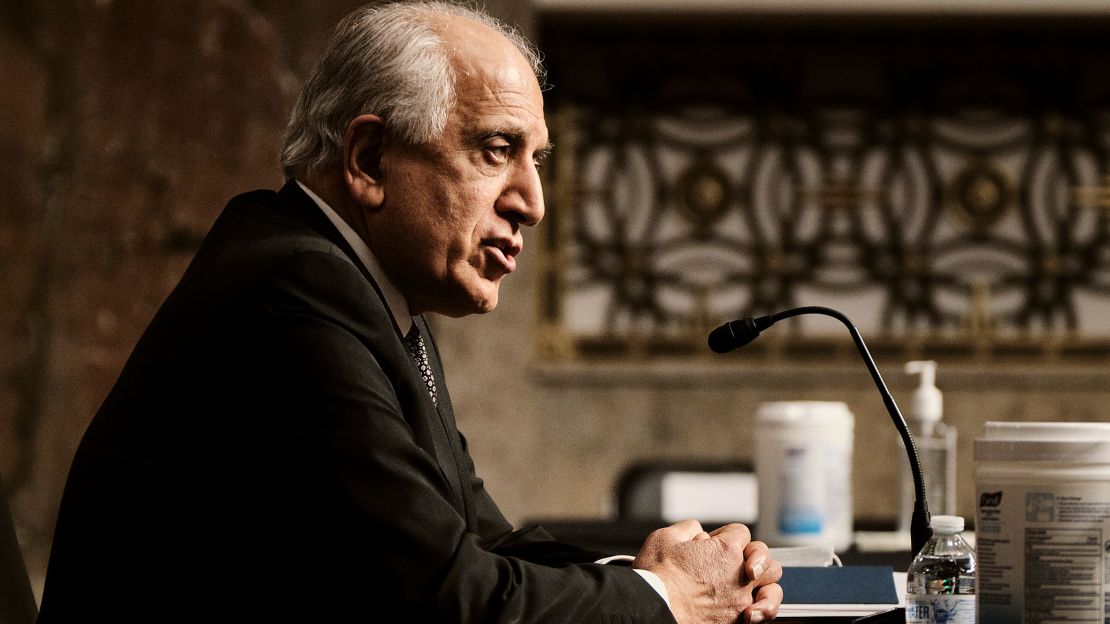

Curtis says that at one point during the negotiations that she was part of in Doha, Qatar, Taliban officials didn’t seem to believe that the US was really leaving Afghanistan, so the top US negotiator, former Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad, brought in American military officers to brief the Taliban about what a US withdrawal would look like.

The US officers used a whiteboard to show the Taliban the unclassified locations of American troop positions in Afghanistan. Curtis recalled that one of the Taliban officials joked, “Oh look, they’re bringing out the crown jewels before we’ve even gotten started.” Curtis said this approach told the Taliban that “the US was really desperate to withdraw.”

In response, Khalilzad emailed us to say, “The technical military channel was set up AFTER there was already an agreement in principle on the withdrawal … These technical meetings had the purpose of dealing with the logistics of both our soldiers and our materiel being withdrawn safely and related issues. Note: this was very successful, and we did not lose a single military member after the signing of the agreement at the hands of the Taliban.”

Curtis says the negotiations with the Taliban were also flawed because the US acceded to the Taliban’s demand that the elected Afghan government be excluded from all their negotiations with the US. Curtis says this gave the impression that the US was “shifting our support to the Taliban, and I think it demoralized the Afghan government, which also contributed to the quick fall of the Afghan government.”

Khalilzad says the decision to negotiate with the Taliban directly was made because “the military situation on the ground was continuing to deteriorate with no roadmap to a plausible near-term victory…The plan was that our success in negotiating with the Taliban would open the door to negotiations between the [Afghan] government and the Taliban.” Khalilzad added, “This indeed did happen, though it did not succeed.”

Why did Biden bring “joy” to the Taliban?

Biden’s top military adviser, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Gen. Mark Milley, told Biden that unless the US kept a small military force in Afghanistan — at the time, around 2,500 troops — the Afghan military would collapse, which would pave the way for a Taliban victory.

Biden, who had long been a skeptic of the war in Afghanistan, ignored this sound advice and, on April 14, 2021, announced the withdrawal of all US forces from Afghanistan.

The Taliban couldn’t believe their luck. When we spoke with the top Taliban spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid, he told us, “When President Biden won the election, we suspected that he might insist on continuing the war. But when he announced that he was withdrawing his forces from Afghanistan, it was a source of joy.”

Compounding the problems of the withdrawal deal with the Taliban, there was acute tension between two key players: the lead American negotiator with the Taliban, Khalilzad, who is Afghan American, and Afghanistan’s then President Ashraf Ghani. The two men had known each other for decades; both had won scholarships to study in the US. Khalilzad received his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, while Ghani’s doctorate was from Columbia University. But now that Khalilzad was leading the US-Taliban negotiations, from which Ghani and his government were excluded, their relationship hardened: They loathed each other.

Khalilzad wrote in his email to us that “discussions with President Ghani became difficult once he realized that a political settlement would require a new Afghan government and the end of his presidency. He had a very strong wish to remain in power. But both Trump and Biden were clear that this wish on his part, was not sufficient reason to put the lives of U.S. soldiers or the policy decision on withdrawal at risk. I had to convey this to him — but that was not personal.”

Matin Bek, who was Ghani’s chief of staff and is now a fellow at New America, and who was often in the room with Ghani and Khalilzad, told us that their tense relationship was “like a wrestling match.”

Bek says both Ghani and Khalilzad share in the blame for the Taliban victory: “They are responsible equally.” As the Taliban closed in on Kabul in mid-August 2021, Ghani, and his key advisers, including Bek, were in Ghani’s presidential palace. A backchannel between Afghan government officials and the Taliban had opened up. Bek was hopeful that a peaceful transfer of power would ensure some normal contact with the outside world, such as the continued presence of Western embassies in Kabul.

But then Bek discovered President Ghani had gotten on a helicopter and fled to neighboring Uzbekistan. Bek felt utterly betrayed, telling us, “He was the president of a country in war. In war, these things happen. You have to show leadership.”

Ghani doubtless recalled that the last time the Taliban had taken Kabul in 1996, they had executed a previous Afghan president. Still, many Afghans felt Ghani should not have abandoned his post.

Biden then shifted any blame from himself in a White House briefing. He had gone along with the flawed withdrawal plan that the Trump administration had negotiated, but instead he blamed the Afghans, claiming, “American troops cannot and should not be fighting and dying in a war that Afghan forces are not willing to fight for themselves.”

This observation irked General Petraeus, who said, “I was particularly hurt by statements ‘Well, the Afghans wouldn’t fight for their own county.’ Sixteen times as many Afghans died for their country as did US and coalition forces.”

Indeed, according to Brown University’s Costs of War project, more than 66,000 Afghan national military and police died fighting the Taliban, while around 4,000 American and allied forces were killed in the Afghanistan war.

What was lost?

In the two decades before the Taliban takeover, Afghanistan had made striking progress in reducing child mortality, providing jobs for women and schools for girls, nurturing scores of independent media outlets and holding regular, if flawed, presidential elections.

That is all long gone.

Why Biden went through with the withdrawal deal is still something of a puzzle, since there was no large constituency in the Democratic Party clamoring for an exit from Afghanistan. Meanwhile, a small contingent of US forces — 2,500 troops — was keeping the elected government of Afghanistan from a Taliban takeover.

When those US troops were stationed in Afghanistan at the beginning of 2021, none of Afghanistan’s 34 provincial capitals were in the hands of the Taliban, but by the time these troops were all withdrawn in the summer of 2021, the Taliban had seized all of those provincial capitals. It’s worth noting also that today, seven decades after the end of the Korean War, the US still stations around 10 times more troops in South Korea than the 2,500 it had kept in Afghanistan, which has helped keep the peace on the Korean peninsula.

Today, the Taliban are international pariahs that no country recognizes as the legitimate government of Afghanistan. Adding to their estrangement from the rest of the world, 58 Taliban officials have been sanctioned by the UN. Of these, 35 hold cabinet-level positions in the de facto Afghan government.

The one relationship that is doing quite well in Afghanistan is the Taliban’s alliance with al-Qaeda. According to the report by the UN released in June, an estimated 400 al-Qaeda fighters live in Afghanistan. Some members of the terrorist group have even received appointments in the Taliban administration as well as monthly “welfare payments” from the Taliban, according to the UN. Afghan Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani, holds one of the most powerful posts in the Taliban’s de facto government and is a member of al Qaeda’s leadership council, according to the UN. Haqqani is also on the FBI’s most-wanted list and has a $5 million reward on his head.

Meanwhile, all you need to know about the Taliban’s mindset, more than two decades after the 9/11 attacks, can be learned by listening to their top spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid, who told us in December that Osama bin Laden wasn’t responsible for the 9/11 attacks. Mujahid asserted, “We do not have evidence that he was directly involved in the attack.” Of course, this is utter nonsense.

Mujahid also claimed to us that the Taliban’s Ministry of Education is making plans to admit teenage girls to school. Two years after the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, there is no sign that the Taliban will allow girls over 12 to be educated.

Instead, the Taliban are running a profoundly incompetent theocratic state that is a magnet for many jihadist groups. And we all know how that can end.