Editor’s Note: Sara Stewart is a film and culture writer who lives in western Pennsylvania. The views expressed here are solely the author’s own. View more opinion articles on CNN.

Has true crime jumped the shark? The heated debate over Netflix’s new “Dahmer - Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story” suggests an evolution is in order for the gruesome genre if it’s going to survive.

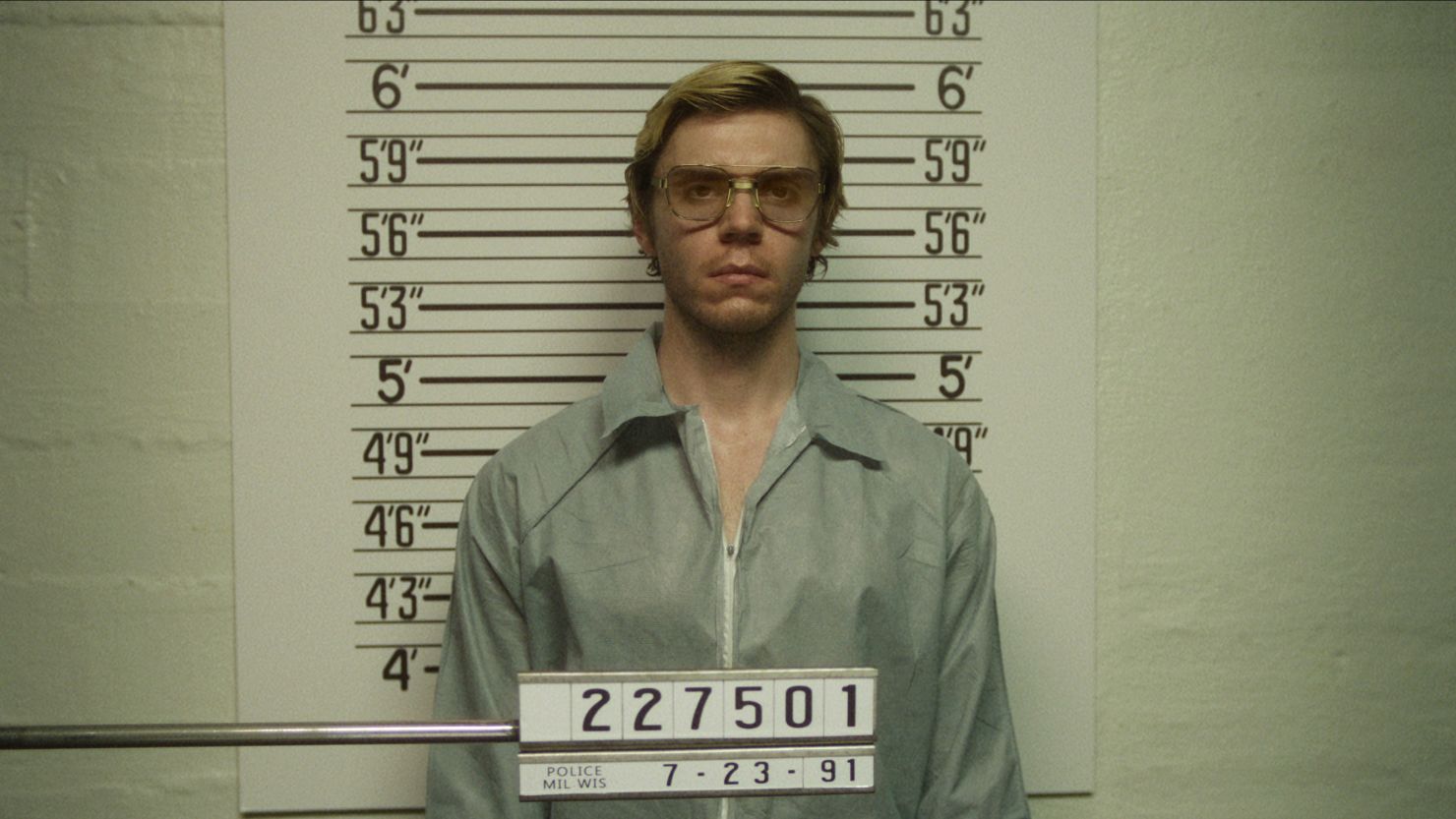

Ryan Murphy’s cumbersomely-titled series, which stars Evan Peters as Dahmer, was the streaming platform’s most-watched new show ever in its first week. But a loud backlash has cropped up around the series’ failure to consult victims’ families, even as the show touts a mission to put their stories at the center of the drama.

Rita Isbell, whose brother was one of Dahmer’s victims, has written movingly about the traumatic experience of seeing her court appearance recreated in Murphy’s series. “I could even understand it if they gave some of the money to the victims’ children…If the show benefited them in some way, it wouldn’t feel so harsh and careless,” she said.

Members of the Black queer community in Milwaukee, where Dahmer lived and preyed, have also gone on the record opposing “Dahmer,” saying its stated intention to center the victims rings hollow. And a Black crew member who worked on the show has tweeted about abysmal, and allegedly racist, treatment on set and about being “re-traumatized” by seeing the show’s trailer.

Murphy apparently hasn’t responded to the show’s critics yet, though Peters has said in an earlier interview that the production “had one rule going into this from Ryan – that it would never be told from Dahmer’s point of view. As an audience, you’re not really sympathizing with him.” But that hasn’t stopped a disturbing trend of viewers lusting after the actor playing serial killer on TikTok and other social media (and in some cases, sharing feelings for the killer himself). The disconnect between Murphy’s professed intentions and the way his series has landed with viewers points to a bigger set of ethical questions about the genre as a whole.

Could the fever of our true crime obsession be at the breaking point? Netflix’s soaring numbers don’t lie, but there’s been a palpable shift toward criticism in the conversation on social media. Friday’s release of “Conversations with a Killer: The Jeffrey Dahmer Tapes,” might just push some viewers into full-blown serial-killer fatigue after a decade-long boom in content in this already-popular genre.

This ghoulish subgenre has been a cash cow for Netflix (and other platforms and networks) for years, but its power over viewers may be receding. 2019’s Ted Bundy drama, “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile,” insisted, via star Zac Efron, that it was pointing out how White privilege allowed Bundy to get away with murder for so long.

But both “Dahmer” and “Extremely Wicked” star handsome young actors, a thinly-veiled invitation to view the famed murderers as, on some level, sympathetic (or at the very least, attractively glamorized). And Murphy’s failure to reach out to those actually affected by the killer has highlighted a related problem: True crime often veers into exploitation even as it maintains that it’s serving up justice, or education or explanation.

Another new series is coming under fire for similar reasons: Lifetime’s “The Gabby Petito Story,” which revisits a crime that’s barely a year old. In August of last year, the 22-year-old Petito was killed by her boyfriend, Brian Laundrie, with whom she’d been traveling around the country in a camper van. A police video shot before Petito’s disappearance, showing cops interviewing the feuding couple and missing all the signs of Laundrie having been abusive, went viral, setting off a firestorm of social media sleuthing and a backlash about the media and law enforcement’s fixation on imperiled White women, while ignoring countless victims of color.

Actor Thora Birch, who made her directorial debut with the Petito movie, told The List in an interview released Sept. 27 that she saw the film as potentially educational for other young women. “Exploring [the story] in as realistic a manner as possible – given the facts we knew – was something that I thought was very intriguing, but also, I saw it as an opportunity for it to maybe be helpful as a cautionary tale.”

Petito’s mother released a statement on the Lifetime dramatization, indicating the family had not been contacted. “We thought our followers should know that the Lifetime movie on Gabby Petito has no connection to the Petito family nor did they give their approval,” she wrote. “Lifetime took it upon themselves to make the movie.”

And earlier this year, Renee Zellweger produced and starred in an NBC miniseries, “The Thing About Pam,” based on a Dateline podcast of the same name about the 2011 murder of Betsy Faria. Faria’s mother and daughter stated they weren’t told about the production, and have said the series got countless facts wrong and took a weirdly comic tone in its depiction of the most upsetting event in their lives. Showrunner Jenny Klein spoke to Entertainment Weekly of the importance of honoring “Betsy’s story, her family’s story, and to honor the truth as we know it,” though she didn’t mention having reached out to them.

Even if both of those series had contacted victims’ family members for consultation and permission, they’re emblematic of another central problem with the true crime genre: Its almost exclusive focus on White people. Says journalist Veronica Wells-Puoane, “For people like me – Black women and other people of color – the true crime phenomenon is a reminder that while we’re being watched, questioned, and regarded with contempt for getting dinner, white folks are literally and figuratively getting away with murder. Instead of calling it for what it is – a travesty – we call this content ‘binge-worthy.’” What’s more, she says, “I fear that these shows, whether documentaries or fictionalized takes, issue a type of sick notice to white audiences…. Commit a crime, and go down in infamy with a Netflix documentary.”

The debate around “Dahmer” also makes for an interesting juxtaposition with the latest “Serial” development, in which accused murderer Adnan Syed was freed after more than 20 years behind bars due to a number of faults in the way his case was handled. “Serial,” the seminal 2014 podcast, was widely credited with putting a spotlight on Syed’s case, though some have also noted that his lawyer Rabia Chaudry did most of the heavy lifting that led to the court’s reversal. Regardless, “Serial” and a handful of other prestige series spawned countless imitators and armchair sleuths, with listeners and viewers of true-crime series hoping to actually help solve cold cases.

But let’s not kid ourselves: the human fascination with terrifying news stories is largely voyeuristic. True crime is addictive because it’s usually riveting. Many true crime series have been meticulously researched and well-told; others simply provide a dark escapism. The statistical scarcity of serial killers makes their stories a safer scare than banal – but more probable – everyday terrors.

Just as there are ways to be a more ethical consumer of true crime, there are more ethical ways to tell true crime stories. Include the victims’ families in the storytelling process. Center the stories of the victims themselves. Don’t include gratuitous or graphic depiction of violence. Avoid the easy play to sensationalism in marketing.

I’m a longtime true crime fan, and I’m sure I won’t give it up anytime soon. But the more we talk about the inherent problems of the genre, the likelier we are to think about what we’re absorbing and what it means for the people who were touched by those events. If we’re going to continue to consume trauma as entertainment, we owe them at least that much.