Brazilians head to the polls Sunday to select their next president in what has been one of the country’s most contested and polarizing elections in recent history.

Although there are nearly a dozen candidates on the ballot – and several other seats up for grabs – the October 2 race is dominated by two frontrunners: right wing incumbent President Jair Bolsonaro and leftist former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, leader of the Workers’ Party.

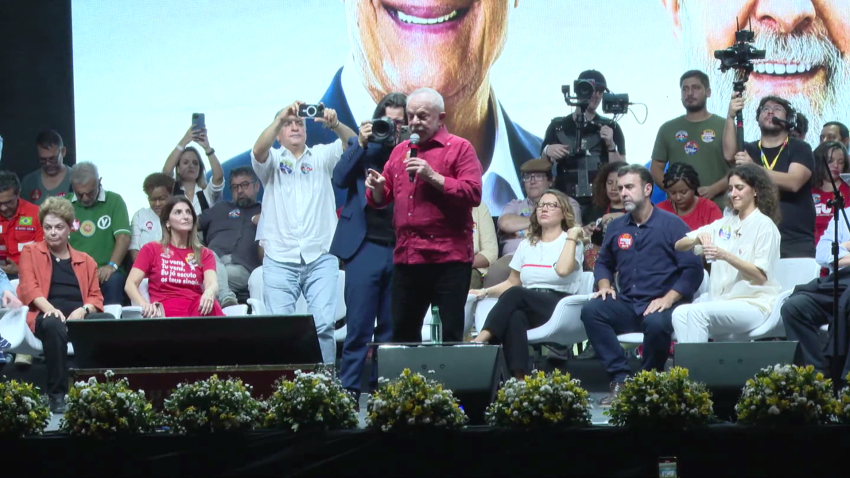

The race is extremely heated. Bolsonaro and Lula, as he is popularly known, have used Twitter, YouTube, televised debates and massive political rallies to present their positions and attack each other at every turn. And violent rhetoric among their supporters has left many voters feeling fearful of what is yet to come.

According to a Datafolha poll conducted in August, more than 67% of voters in Brazil are afraid of being “physically attacked” due to their political affiliations. And the country’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal has issued a ban on firearms within 100 meters (330 feet) of any polling station on election day.

Both candidates have been seen on the campaign trail flanked by security and police, even wearing bullet proof vests at times. Bolsonaro wore his as he kicked off his reelection bid last month in the city of Juiz de Fora, at the exact location where he was stabbed in the stomach during the 2018 presidential campaign. Lula was seen also wearing a vest during an event in Rio de Janeiro, the same city where a homemade stink bomb was launched into a large crowd of his supporters back in July.

Lula and Bolsonaro: Ideological opposites

The race pits two titans of contemporary Brazilian politics – and polar opposites – against each other.

“These are two well-known figures, two of the largest and most unique populist leaders in Brazilian politics from the past 20 years,” Antonio Lavareda, director of Brazilian polling group Ipespe, told CNN affiliate CNN Brasil.

“For the first time, we have a president who is being evaluated based on his nearly four years in office and a former president who already has a consolidated image.”

Bolsonaro, 67, who is often referred to as the “Trump of the Tropics,” is running for reelection under the conservative Liberal Party. At the center of his campaign and his reelection plan is what he says is the right for freedom: freedom of expression, freedom to live and freedom to use the country’s natural resources for future development and growth, including in mining and other agricultural businesses. Bolsonaro’s job creation strategy is based on investing in industry to promote job growth, especially in tech. The former paratrooper also supports expanding access to gun ownership for self defense.

Bolsonaro’s record from his first term could be a liability. He was widely criticized in Brazil and abroad for his mishandling of the Covid-19 pandemic in Brazil, which killed more than 685,000 people, and for a spike in deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon under his presidency, among other things.

Lula, 76, was president of Brazil for two consecutive terms from 2003 to 2011. On the campaign trail, he has mostly focused on getting Bolsonaro out of office and has leaned heavily on the achievements of his previous presidential terms. He left office with a 90% approval rating and is largely credited for lifting millions of Brazilians from extreme poverty through “Bolsa Familia” welfare program.

“I don’t need to make any promises to you,” Lula said during a recent campaign stop in Sao Paulo. “My policies are endorsed by the legacy of my previous eight years in power, which were very successful for this country and all sectors of society.”

Lula was convicted for corruption and money laundering in 2017, on charges stemming from the wide-ranging “Operation Car Wash” investigation into the state-run oil company Petrobras. But after serving less than two years, a Supreme Court Justice annulled Lula’s conviction in March 2021, clearing the way for him to run for president for a sixth time.

“I didn’t need to be president again. I could keep my title as the ‘best president in history’ and go live the last few years of my life in peace. But I saw this country destroyed. I saw education run by a guy who didn’t like education. So, I decided to go back,” Lula said in July, when he officially accepted his party’s nomination.

Sowing doubt about the vote

Several polls show Lula in the lead. The latest poll, released on Thursday by respected research group Datafolha, showed him ahead of Bolsonaro by 14 points, just three days before the Sunday vote.

After Datafolha ruled out blank and undecided voters, its model found Lula at 50% among valid voters, versus the 36% who said they would support Bolsonaro. This margin increased in the hypothetical scenario of a second round, showing Lula with 54% of the vote versus Bolsonaro’s 39%, according to Datafolha. Other national pollsters, such as Ipec and Ipespe, has increasingly undermined supporters’ faith in the vote itself.

Without presenting proof, Bolsonaro has claimed that the country’s electronic voting system could be rigged and even said it had been tampered with in the past. There is no record of fraud in Brazilian electronic ballots since they began in 1996.

He has also cast doubt on his country’s election authorities. During his recent trip to London for Queen Elizabeth II’s funeral, Bolsonaro told Brazilian broadcaster SBT, “If we don’t win during the first round of voting, something abnormal happened within the Supreme Electoral Tribunal.”

Critics have warned that such talk could lead to outbreaks of violence or even refusal to accept the election result among some Brazilians – pointing to the Jan. 6, 2021, riot incited by then-US President Donald Trump after he lost the vote.

There have already been several reports of political discourse among Lula and Bolsonaro supporters turning violent, even deadly.

Over the weekend, police registered two fatal incidents in states on opposite ends of the country. In the northeastern state of Ceara, a man was stabbed to death in a bar after identifying himself as a Lula supporter, according to police. And authorities in southern Santa Catarina state say a man wearing a Bolsonaro T-shirt was also fatally stabbed during a violent discussion with a man whom witnesses identified as a Workers’ Party supporter.

Police say they are investigating both incidents and that arrests have been made.

The hostility is attracting global concern. UN human rights experts issued a statement earlier this month urging Brazilian authorities, candidates and political parties to ensure a peaceful vote.

“We are concerned that this hostile environment represents a threat to political participation and democracy and urge the State to protect candidates from any threats, acts of intimidation or attacks online and offline,” the experts said.

“All those involved in the electoral process must commit themselves to peaceful conduct prior, during and after elections. Candidates and political parties must refrain from using offensive language which may lead to violence and human rights abuses.”

Many voters have already made up their minds

In order for either candidate to win in the first round of voting, they need to get an outright majority – meaning more than 50% of the votes. If neither candidate reaches that amount, a runoff is scheduled to take place on Sunday, October 30th.

But the fear factor among voters could lead to a large number of abstentions this Sunday.

“This election, unlike any other election since 1989, has a high number of voters who are afraid to talk politics, to talk about the election. This could have a direct impact on whether people go to the polls,” Creomar de Souza, a political scientist and founder of Brasilia-based Dharma Political Risk and Strategy, told CNN Brasil.

“We’re seeing cases and incidents of violence and other types of aggression and humiliation, which are making people feel scared.”

But that doesn’t mean they don’t know what they want. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the high-wattage personalities vying for Brazil’s presidency, there are fewer undecided Brazilians this year, De Souza pointed out.

“If you look at the metrics in this election, we have the lowest number of undecided voters since Brazil’s return to democracy. Numbers are ranging from 4% to 6%, but no polling institute has any number above 10%,” De Souza said.