My entire life has been shaped by my late grandfather and his stories of heroism during World War II.

My grandpa, Frank DeSales Murphy, survived months in a German POW camp after being shot out of his B-17 Flying Fortress. He withstood a harrowing death march in sub-zero temperatures – and his bravery earned him the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Purple Heart and the Air Medal.

The incredible stories of my grandfather and his 8th Air Force’s 100th Bomb Group – nicknamed “The Bloody Hundredth” – will be featured in the upcoming Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks Apple TV series, “Masters of the Air” written by “Band of Brothers,” John Orloff.

Like most of his fellow war comrades, grandpa didn’t talk about his experiences until decades after the war.

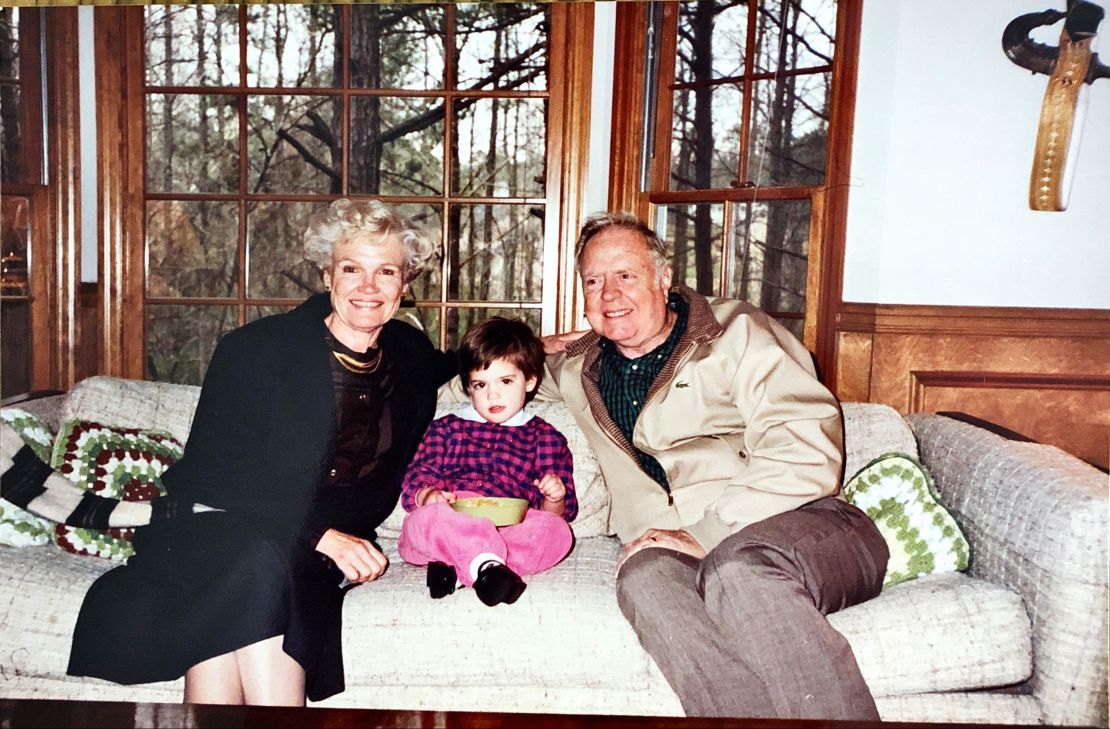

As a little girl, I spent most of my weekends at my grandparents’ home in Atlanta, Georgia where grandpa would tell me bits and pieces about his WWII combat missions. His stories sounded like fairytales, conjuring up images of him flying over mountains and oceans in far-off lands.

As I got older, I began to ask more questions and explore his home office which was frozen in time with photos all over the walls and newspaper headlines from his time during the war. To this day, my grandmother has kept that room intact.

Every time I return to Atlanta from New York, where I live now, I sit in his desk chair and try to remember the sound of his soft southern voice telling me about how he survived and that – just like the title of his book – it just came down to “the luck of the draw.”

Now, as a mom of two, I want to make sure my sons grow up knowing the hero that fought for their freedom.

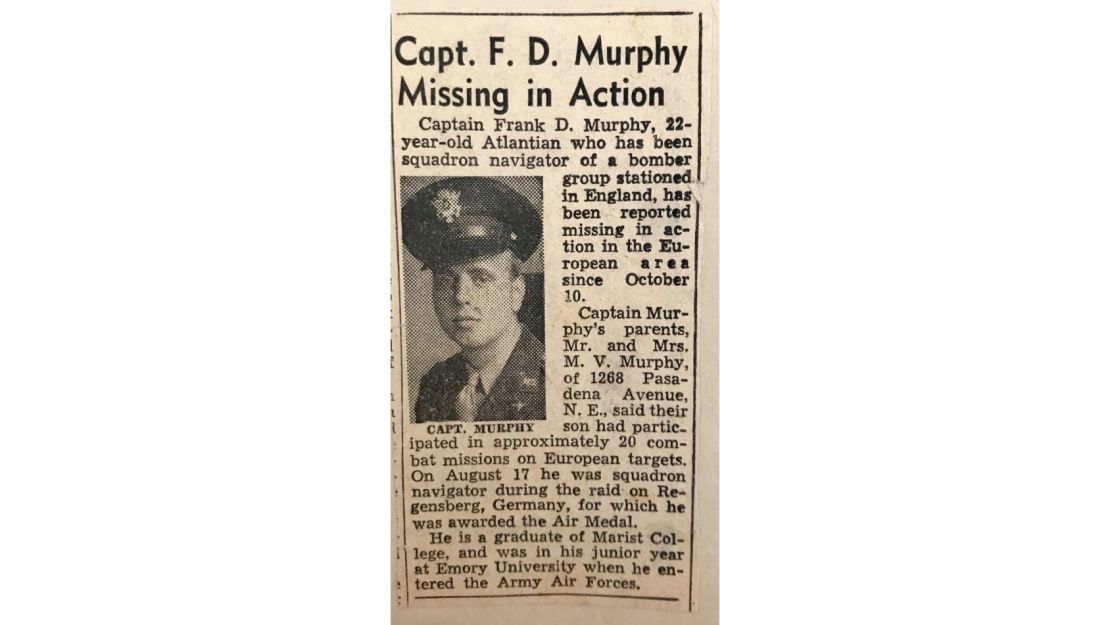

Missing in action

One of the most significant dates during my grandfather’s journey happened on October 10, 1943, when – at 22 years old – his luck quite literally ran out. The aircraft, piloted by Capt. Charles “Crankshaft” Cruikshank, with my grandfather as the plane’s navigator, was taking part in a maximum effort strike by 215 aircraft of the Eighth Air Force (“The Mighty Eighth”) based in England.

They were on a mission to bomb the railroad marshalling yards at Munster, Germany. But before they could reach their destination, they were met by 250 Luftwaffe single and twin-engine fighter aircraft. Despite the odds, my grandfather’s plane, “Aw-R-go” managed to release its bombs over the target before they were hit.

Two fires engulfed the bomber and my grandfather and his fellow airmen were forced to abandon the aircraft. That meant parachuting out. My grandfather narrowly escaped death that day and was lucky to only have shrapnel in his shoulder when he landed in a German farmer’s field. The family brought him in, bandaged him up and years later he would return to the farmhouse and became friends with the family who turned him over to Nazi authorities.

Forty-six members of the “Bloody Hundredth” were killed in that air battle, and only one of their planes returned home that day, piloted by Robert “Rosie” Rosenthal. Later in life I became friends with Rosie’s son, Dan, who is now the president of the 100th Bomb Group Foundation and I frequently go to their reunions to meet with the remaining veterans and other family members of the 100th. I like to think that would make my grandfather smile.

On the day my grandfather’s B-17 was shot down, two members of his crew died and 177 men from this air battle became prisoners of war. My grandfather was one of them.

For the next few months, his parents would have no idea what had happened to him. They only knew that he was missing in action. It must have been pure torture for them. A few months later, they would learn that he was a prisoner of war along with 110,000 other Allied troops at the infamous Stalag Luft III prison camp, near Sagan, Germany.

It was here that the Great Escape of 1944 took place in which more than 70 Allied POWs tunneled out of the prison camp. Nazi forces captured and executed 50 of the escapees, a direct violation of the Geneva Conventions. This would go down in history as one of the more egregious acts against prisoners of the war carried out by Hitler. The story was forever immortalized in the 1963 movie “The Great Escape” starring Steve McQueen.

In his book, my grandfather described the horrid conditions at the POW camp:

“We had one cold-water spigot in each building; they were our only source of water for every purpose,” he wrote in “The Luck of the Draw.” “The fortunate ones among us slept on triple-deck wooden bunks on gunnysack mattresses filled with excelsior and infested with fleas, lice and bedbugs – the unlucky ones slept on floors, tables, or outside on the ground inside crowded tents.”

My grandfather found solace in music, which he credited with his survival during the war. He learned how to play the saxophone and clarinet in a POW swing ensemble using instruments donated by The Red Cross. He would go on to play those same instruments in bands as a hobby for the rest of his life.

A brutal march, freedom and meeting General Patton

My grandfather’s experience during World War II is full of harrowing moments like the death march from Stalag Luft III to Mooseburg’s Stalag VII A, a prisoner of war camp in Bavaria about 20 miles northeast of Munich. It was built to accommodate only 10,000 people, but over 100,000 POWs from military personnel of every Allied European nationality were housed there.

My grandfather described a “dark, bitterly cold winter night” on January 27, 1945, when Hitler ordered the guards to evacuate all of the American and British officers to the west due to the Russian Army advancing to liberate their troops from the camp. At around 11 p.m., my grandfather said they grabbed their “pitiful belongings” and began to walk in the “deep snow” to a “God-only-knows-where destination.”

What he didn’t know was that they would march for the next three days and nights in sub-zero temperatures with little rest and nearly no food or water. Many men did not make it, with my grandfather telling stories of how men would collapse in the snow from the exhaustion and freezing weather.

He said they would plead with them to not give up. He actually traded his shoes with a fellow soldier, as his leather soles were soaked and he was given a pair of wooden clogs. I have one of those shoes – we don’t know what happened to the other. My grandmother jokingly says they used it as a planter in their home years later. I have the surviving sole clog that I’m safely safeguarding for my sons (no plants are going in this one, grandma).

After marching for days, they were crammed into boxcars for two days and three nights. My grandfather would tell me how the Germans refused to open the doors to even allow a bit of sunlight or fresh air in. He arrived in Moosburg on February 1, 1945 where he would stay for the next three months in what he said was a “living hellhole of all hellholes.”

But his luck would turn around on April 29, 1945 when units of Gen. George Patton’s American Third Army would liberate over 100,000 POWs from the horrific conditions.

My grandfather had lost over 50 pounds, weighing just 122 pounds when he was liberated.

The day he was finally freed was one of my favorite stories that I would repeatedly have my grandfather tell. My eyes would widen to the size of silver dollars when he would tell me how three US Sherman tanks would crash through the main gates of the prison camp. He said seeing the white star on the side of the tanks brought tears to his eyes.

A few hours later, the American flag – “Old Glory” as they affectionately called it – would be hoisted to the top of a church steeple in town as the POWs stood there, tears streaming down their faces at the thought of going home and the pride for their country.

The next day on April 30 Adolf Hitler committed suicide in his Berlin bunker. Then on May 1, General Patton paid a visit to Stalag VII A. My grandfather would tell me about how vividly he remembered Patton’s crisp uniform with his black leather belt with its huge silver buckle and his famous ivory-handle revolvers.

Patton stopped to meet with different groups of American prisoners that day. When he came up to my grandfather, Patton shook his head in disgust at how thin and malnourished they were and he looked at my grandfather and said, “I’m going to kill these sons of b**ches for this.”

Sometimes we would all laugh when he told that line because my grandfather’s voice would get all serious and he never cursed.

On May 7, Nazi Germany would unconditionally surrender to the Allies and the following day, Victory in Europe or VE Day was celebrated worldwide. The reign of Hitler’s Third Reich was over.

My grandfather made his way to Camp Lucky Strike in LeHavre, France a rehabilitation center for American POWs, where he learned, unsurprisingly, that he had pneumonia. He said he was treated with a new miracle drug, penicillin.

A few days later he boarded a large troop ship, “Argentina” to set sail for America. It would take 12 days before he made it to Boston and then shortly thereafter back to his family in Atlanta.

He would eventually complete his studies at Emory University, marry my loving and outspoken grandmother, have four children and attend law school at night. He returned to his love of airplanes later in life as the vice president for Lockheed Martin Corp.

A return to where it all began

Once I reached college, my interest in my grandfather’s combat missions and experience as a POW only heightened. During the summer of 2006 after my freshman year, I was studying abroad in London – just a few hours away from Thorpe Abbotts Royal Air Force station, where my grandfather flew out on 21 perilous missions during WWII.

That summer I learned my grandfather was diagnosed with cancer. I decided to make the two-hour train ride from London to Thorpe Abbotts, which is now a museum.

I’ll never forget the museum’s caretaker Carol Batley walking me into the air traffic control tower on the base which is now filled with uniforms in glass cases and some personal belongings of the men who were stationed there – including my grandfather’s.

We walked in and she said, “Hello, boys” as if they were all still standing there in the control tower. The hair on my arms stood straight up, it’s a moment I’ll never forget.

I then found myself on the runway where I called my grandfather from my tiny little pre-paid Vodafone. At 84 years old, it was the first and last time I ever heard him cry.

“I’m here,” I said to him. He broke down responding, “That’s where it all began.”

He died that next summer almost to the day. Going there was one of the best decisions I’ve ever made.

Today, I now proudly serve on the board of directors for the Mighty 8th Air Force Museum in Pooler, Georgia, just as my grandfather did.

I’m teaching my sons why the men and women of WWII are so famously called the Greatest Generation. At night we talk about Frank and his plane flying high in the sky. My 3-year-old son Leo frequently asks me about him at bedtime and tells me he wants to fly planes like grandpa.

My grandfather once told me he spent the rest of his life walking with ghosts but looking back with pride. My goal is to keep his memory and that of his fellow men alive and try to pass on the greatness to the next generation.

Historian and author Mike Faley contributed to this story