“I came to rugby because the door of my school gym was glass,” says Jean-Pierre Rives, “and I went through it.”

It was, in many ways, a fitting introduction to the game for a man who never found self-preservation to be a high priority.

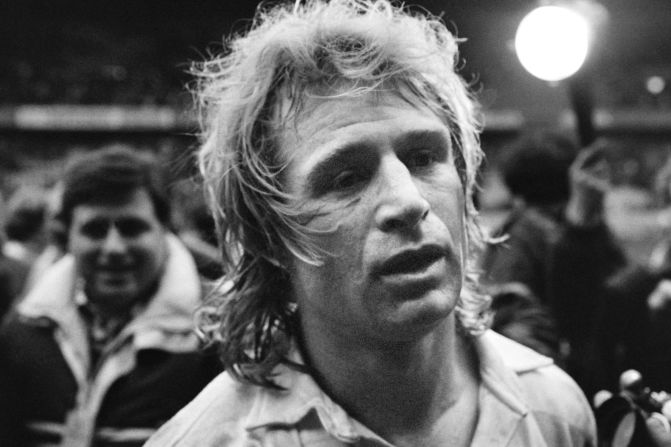

The image of a bloodied, bandaged Rives – nicknamed “Casque d’Or” (“Golden Helmet”) because of his blonde mop of hair – is a defining one for those who followed rugby in the 1970s and 80s.

Yet it could have been so different had that shy, 13-year-old boy not been hurled through a gym door during a rough, playground game; nor had the teacher on duty not brushed him down and suggested he join the local club rugby team.

It was a decisive moment. Rives went on to play for his country 59 times, captaining Les Bleus on 34 occasions. He led France to two grand slam triumphs in 1977 and 1981, and the nation’s first ever victory in New Zealand in 1979.

Since retiring, he has focused his energy on sculpture, for which he has earned critical acclaim with his work exhibited around the world.

Flanker, captain, artist -- the life and career of Jean-Pierre Rives

It’s for his rugby, though, that Rives is best remembered – a fearless flanker who played the game with a commitment rarely seen before or since.

“When you’re young, you’re indestructible,” Rives tells CNN in an exclusive interview. “You just use your body as a weapon.

“There were lots of big guys and I wasn’t so big, so I had to find something else.”

And that something else wasn’t just unwavering courage; it was also a deep respect for the game and for those playing it. For Rives, rugby has always been more than 30 men and a ball; it is unity, brotherhood, and sacrifice – a means of expression shaped by those you share it with.

“The best thing about it was just being with great guys,” he says. “I have so many friends now and so many memories; we’re made of this.

“Rugby, it’s a way of life, it’s a spirit, an état d’esprit – a state of mind. For me, it is the way I am and I’m still the same because of it.”

READ: How becoming paraplegic inspired an Englishman to tackle HIV in Swaziland

French flair and France’s leader

The team Rives captained exemplified French rugby as a whole, playing with élan – a certain style and flair – that was exuberant, fast-moving, and eye-catching. It’s something that many regret the loss of in today’s French team with its heavy forward pack and increased focus on percentage rugby.

For Rives, he has no doubt it’s the way the game should be played. Be they teammates or opponents, he couldn’t help but admire rugby’s most gifted attackers.

“Without freedom, there’s no energy, and without energy there’s no invention. I love players who can invent something, who can create something extraordinary, who are unpredictable.

“We talk about French flair, but we didn’t really know what it was. I remember when [Serge] Blanco was playing, nobody knew where he was going, and I’m not sure he knew himself. But mostly he was going the right way.”

READ: England can’t offer Eddie Jones ‘unconditional’ support

When Rives first took up rugby, he would beg with the coach to let him play center, only to be told that he was a great tackler and needed in the forwards – but next time he could play center.

The next time never came.

“I dreamed all my life of being Gareth Edwards or Phil Bennett or so many of the players I admire like Serge Blanco. Myself, I just played rugby. Those players, they payed something different.

“Unfortunately, I didn’t have enough talent to play like this, but what a pleasure it was to play at the same time as them.”

Rives never thought himself a talented player, but his heart-and-soul commitment – in a test match or on the training ground – was what set him apart.

He would train twice a day, often by himself, and in team sessions led by example. Richard Escot, a long-term writer and correspondent for L’Equipe, singles out France’s first ever victory against the All Blacks in New Zealand.

“France lost the first test and were very upset,” says Escot. “Jean-Pierre said nothing, apart from, ‘okay, we go training.’ He was the first in training and he put in so much energy that everybody followed without a word. Not a word, nothing – they just followed.

“He wasn’t the kind of captain who screamed or shouted, but he’s the only one players will follow into the gates of hell.”

READ: Tragedy inspires World Cup winner Will Greenwood to trek to the North Pole

Escot forged a close friendship with Rives after authoring “Rugby & Art”, a series of conversations between the two men. In his eyes, Rives is France’s greatest captain. He says the only player today who’s perhaps comparable is Australian superstar David Pocock.

“Jean-Pierre always put his head where nobody would put their toes,” says Escot.

“He was really out of this world, and would still be tremendous if he was playing now. He’d put his hands on the ball and nobody would be able to move him.

“If you were under Jean-Pierre Rives’ captaincy you should act for others. You should be a good man, an altruist, not thinking about yourself, but thinking about the team and what the French national jersey means to you.”

Steel, sculpture, and self-expression

It was while watching his friend and mentor Albert Féraud that Rives was first inspired to become a sculptor after retirement from rugby.

Working mainly with huge steel beams gathered from scrap heaps, Rives’ creations, which have occupied the past 30 years of his life, have been displayed at notable exhibitions in Paris, Toulouse, Sydney, and New York.

His form is abstract – “it’s not clear in French, let alone English” – he confesses, but says the impulse to create is what motivates him most, whether the end results please him or not.

“Sculpture is so important for me,” says Rives. “To be is to make something, to invent something.

“When you’re making something you’re not really looking at it. After a while you pass it again and see it and see something interesting in it, and other times you think, ‘My God! What is this?’”

Rives’ interest in rugby remained after retirement through the French Barbarians, a team he co-founded alongside his teammates from the 1977 grand slam-winning side.

And it’s not to say that, with sculpture, he’s lost sight of what he held so dear about rugby.

“It’s the same in lots of ways, rugby and sculpture – you express yourself through something,” says Rives. “When you play rugby, you try to express yourself with your body, with your soul. In art, it’s something else – color or form.

“It’s the process that’s important to me, not what you’re doing; do anything, but do it.”

For Rives, doing is important.

He sculpts, he paints, he’s a trained classical pianist, but admits he’d rather have played jazz.

He speaks enthusiastically about golf – “an incredible sport” – and as a boy qualified for the French Junior Championships at Roland Garros.

He discusses with sincerity the important of literature, art, and, above all, friendship.

Visit cnn.com/rugby for more news and videos

All of this energy, you feel, was put on show when Jean-Pierre Rives took to the rugby field – a man for whom the sport was always bigger than life itself.

“Most people can put rugby into life,” says Escot, “but he’s the only one who could put life into rugby.”