Editor’s Note: James Ball is an award-winning journalist and author who has worked for Wikileaks, the Guardian, the Washington Post and BuzzFeed. The opinions in this article belong to the author.

(This article was originally published on May 11, 2018.)

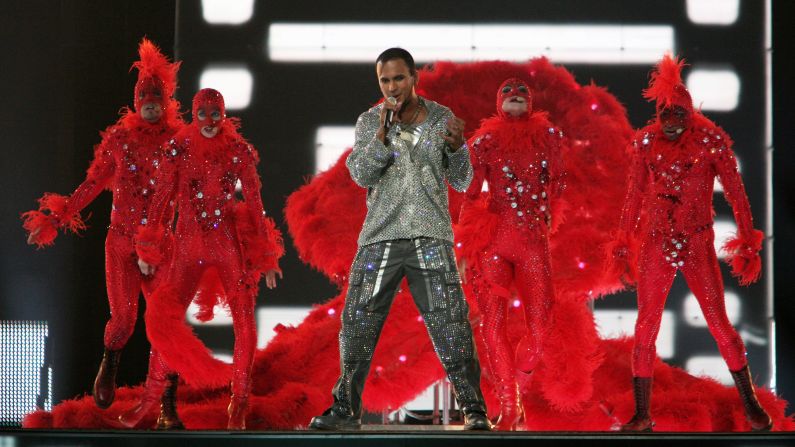

This Saturday, performers from 26 countries and thousands of fans will congregate in Lisbon for the 2018 final of the Eurovision Song Contest – a huge international singing contest whose format, voting and bizarre politics make it all but incomprehensible to anyone who isn’t from one of the participating countries.

The contest is only one of the ways that many of the countries concerned come together to participate in anything.

It takes in all of Europe’s nations: from the Western edge of the European Union to the Balkans, as well as Russia and, in recent years – with really very little explanation as to why – Australia.

The contest’s format is sprawling: 37 countries compete in one of two semi-finals to secure one of 20 spots in Saturday’s final. An additional six countries automatically get spots in the final by virtue of covering most of the bill for the event.

Each country picks an artist (some through huge public votes, some behind closed doors) to perform a song that lasts no longer than three minutes. Eventually a winner is chosen.

It’s the voting system that makes Eurovision what it is to so many, though. Aside from election nights, Eurovision is perhaps the only night when millions of viewers will watch for several hours as a series of numbers are read out, usually by glamorously dressed presenters whose sole job for the night is to say things like “Hello from Riga,” followed by a list of scores.

Each country allocates two different sets of scores. One set is put together by a “jury” of experts; the other is determined by a telephone or text vote of the viewing public of that country.

The system has become notorious among Eurovision fans for enabling countries to do favors for their neighbors and allies – Croatia, for example, will almost always find any song by Bosnia & Herzegovina better than other judging countries will.

The intricate system leads fans to obsessive numerology, and subsequent statistical analyses reveal that European politics do indeed influence the vote. Analysis of 18 years’ of Eurovision voting by BuzzFeed News (a confession: this analysis was partly conducted by me) found three voting “clusters” of countries more likely to award each other points – that largely track Europe’s regional politics.

Two of the groups are quite tightly focused: one is largely composed of the nations which used to be part of the former Yugoslavia, while another is made up of former Soviet states and some of the southeastern European nations. The nations of Northern and Western Europe make up a larger group, but this one is more diffuse because there are so many countries inside it.

The result is that the winner of the contest is not just about music, but also about politics and the state of European nations’ (and Australia’s) mood: how do we feel about each other? But the music matters too, as perhaps the world’s paramount Eurovision nerd, Kit Lovelace of Popbitch, has determined.

His extensive analysis suggest songs should be in a minor, not major, key; should avoid being either 128 beats per minute or 85 beats per minute; should mention night, bad weather or religious imagery in their lyrics (and avoid mentioning sunshine, tears or souls); and if they can possibly help it have women both singing and dancing on stage.

The contest is ridiculous and unfair. Countries with a population of 33,000 are pitted against ones with 70 million. Some countries put up their biggest stars and writing teams; others treat it as a joke. Some countries even get to skip qualification and jump straight to the final. And the quality of the entry is just a fraction of what it takes to win.

And it’s this that is the joy of the contest. The nations competing in Eurovision are polarized and fractious, both with one another and within themselves. Having an absurd, intricate – and when many countries concerned have questionable LGBT records, unabashedly camp – and joyous contest is the ridiculous release Europe needs.

Long may it continue.