Story highlights

Pots that still have food in them have been found at the site

It's the best-preserved Bronze Age village ever found in England

Scientists hope to find out how the villagers died

“It feels almost rude to be intruding. It doesn’t feel like archaeology any more. It feels like somebody’s house has burned down and we’re going in and picking over their goods,” Mark Knight says.

Knight is the director of a remarkable project: the excavation of the best-preserved Bronze Age village ever found in Britain.

Lost deep in the marshlands of eastern England, in a clay quarry not far from a frozen french fry factory, the Must Farm site is yielding secrets from 3,000 years ago.

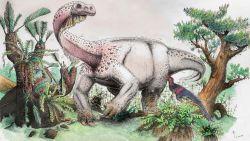

Two newly discovered Bronze Age dwellings provide an extraordinary insight into the domestic life of our ancestors.

These large, circular, wooden houses, built on stilts above water, would have been home to several families.

The settlement, dating to 1200 to 800 BCE – the end of the Bronze Age – was destroyed by a dramatic fire and collapsed into the river, preserving the contents in situ and in an astonishing condition.

As a result, archaeologists are finding rare small cups, bowls and jars, even a cooking pot containing a wooden spoon and the remains of grainy porridge, which suggests the last meal in the house was abandoned as the owners fled the fire.

Ancient footprints preserved

“We are learning more about the food our ancestors ate, and the pottery they used to cook and serve it. We can also get an idea of how different rooms were used,” says Duncan Wilson, chief executive of Historic England, a government agency helping to fund the work.

See inside a Bronze Age village

Literally following the preserved footprints found on the site, we encounter glass beads forming part of an elaborate necklace and exceptional textiles made from plant fibers such as lime tree bark. These were obviously relatively wealthy families.

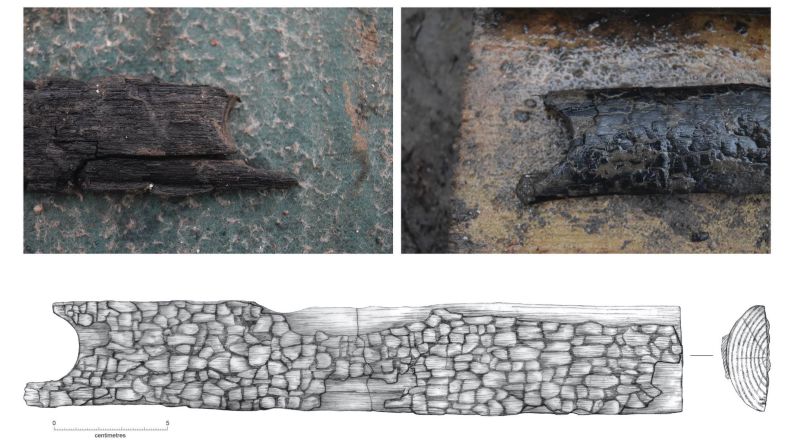

Clearly visible are the well-preserved charred roof timbers of one of the roundhouses, timbers with tool marks and a perimeter of wooden posts fencing off the settlement.

The finds, taken together, provide a fuller picture of prehistoric life in Britain than we have ever had before.

“It is a window of opportunity to explore this lost world,” Knight says.

1,200-year-old Viking sword discovered by hiker

Secret location

The site came to light in 1999 when a local man, Martin Redding, spotted a wooden post on the side of a disused quarry. After 15 years of intermittent research, the current dig started in September and will continue through March.

Once the digging is complete and further analysis and conservation has been done, the findings will be displayed at Peterborough Museum and at other local venues.

The enterprise is being co-funded by brick manufacturer Forterra, which owns the Must Farm quarry.

The site, the exact location of which we’ve been asked not to reveal in order to protect it, is 1,100 square meters and 2 meters (6 feet) below the modern ground surface.

Knight and his colleagues suggest there is much more to be discovered as work continues over the coming months.

“The roof of the building collapsed, and what’s fantastic is that there is a sort of hump beneath that center, which suggests the contents of the building are underneath the roof as well. So over the next few weeks we will take the roof away and see what’s underneath,” Knight says excitedly.

A human skull has already been found on the site. In the coming weeks, we might learn how the fire started – and find out what happened to the people in those houses.