Story highlights

Richard III's remains were found beneath a car park in Leicester in 2012

Long-lost King's skeleton is to be reinterred in the city's cathedral later this week

Bones will be buried in a coffin made by Richard III's descendant, Michael Ibsen

Cabinet-maker Michael Ibsen has just put the finishing touches to a coffin; built of highly-polished, honey-colored English oak and yew, it has been a labor of love, pondered over and painstakingly crafted.

Because this isn’t any ordinary commission: the casket will be the final resting place of one of Ibsen’s distant relatives, Richard III, who died more than 500 years ago.

“It is a unique privilege,” says Canadian-born Ibsen, whose DNA was used to establish the identity of the English King, found buried beneath a car parking lot in the city of Leicester in August 2012.

“There’s a wonderful serendipity in a sense that someone involved in the identification of the remains should happen to be furniture maker who can do this.

“When you’re working away you just focus on joining two bits of wood, but at the end of the day when you stand back and think ‘I’m building Richard III’s coffin,’ it’s incredible.”

Ibsen says he’s been on an “extraordinary journey” in the two-and-a-half years since he gave a DNA swab to genetics specialist Turi King on the off chance that experts searching for the burial place of his seventeen-times great-uncle might strike it lucky.

Back then even the man in charge of the dig, archaeologist Richard Buckley, didn’t expect to find anything – he told colleagues he’d “eat his hat” if they turned up the long-lost King’s remains.

“When we were planning the project, I never made any secret of the fact I thought it very unlikely we’d be successful,” Buckley told CNN. “The chances of hitting the right spot were very slim.”

Call it a fluke, or call it fate, but as it turned out they hit the right spot almost immediately: Richard III’s skeleton was found on the very first day of the dig, in the first trench dug by the team.

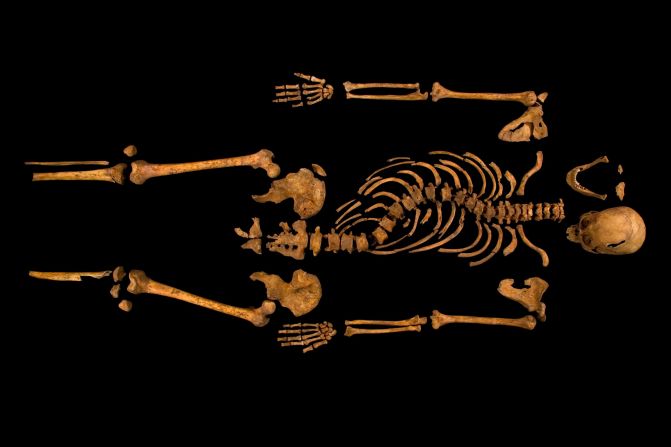

At the time, all the experts knew was that they’d found a set of leg bones, chopped off at the feet by building work at some point in the intervening centuries.

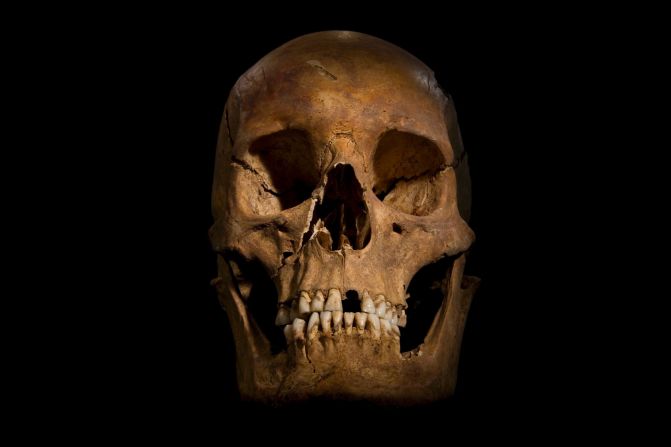

It wasn’t until days later, as archaeologist Jo Appleby carefully exhumed the rest of the skeleton that she spotted the distinct curve of its spine, and the devastating damage medieval weapons had left on its skull.

For Philippa Langley, founder of the “Looking for Richard” project, who stood watching with bated breath as the bones were uncovered, the discovery was a vindication of the years she had spent trying to get people to search for the King’s remains – and to look again at his reputation.

Say the name Richard III to many people, and the image which will spring to mind is that of Shakespeare’s villain, hunchbacked and murderous, who met a grisly end on the battlefield at Bosworth after killing his nephews, the Princes in the Tower.

Years of research had convinced Langley of two things: firstly, that his remains lay underneath a car park, in what had once been the Grey Friars’ monastery, and secondly, that he was much-maligned, the victim of bitter Tudor propaganda after his death.

Two-and-a-half years on, Langley believes the discovery – which proved her first theory to be correct – and the scientific research carried out since, have forced a rethink of Richard III’s story.

“As a writer my view of Richard has always been that he was a very complex, very conflicted, very flawed individual – that’s the human condition: We are all flawed, complex, conflicted – but there was something heroic about him, he was courageous on and off the battlefield,” she explains.

She says DNA evidence that the King was blue eyed and fair haired – in contrast to portraits and written descriptions which painted him “as a hunchback, with a withered arm and a crippled gait, with ‘evil’ dark eyes and hair” – had “blow[n] the mythology out of the window.”

“It makes people question, drop their preconceptions, forget their assumptions, and go back to the beginning,” she says.

This weekend, Richard III’s skeleton will leave the laboratory at the University of Leicester, where it has been kept since it was found, and be taken back to Bosworth, scene of his death in 1485, for a commemoration ceremony, before being returned to Leicester ahead of its reburial next week.

And while his body last made that trip slung unceremoniously over the back of a horse, this time the journey will be done in style: carried in the coffin made by his great-nephew.

Inside, the smaller bones from his hands and feet will be tucked into linen bags – each one decorated with a rose, representing the House of York, Richard III’s family – sewn by children from Leicester’s King Richard III Infant School.

“I feel very proud because I’ve never made a bag for a king before,” said Xi Chen, who helped make the pouches. “It’s like I’m a servant doing something for a King,” added his classmate Irfan Sheikh.

Lead conservation specialist Jon Castleman – who previously helped to restore the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem – will be the last person to set eyes on the skeleton, as he welds the ossuary inside the casket shut.

Well-wishers are expected to line the route as the cortege winds through the Leicestershire countryside, stopping at several churches along the way for prayers and religious services before making its way back to Leicester Cathedral, near the site of the archaeological dig, where a new tomb has been built for the King.

Historian John Ashdown-Hill, who discovered the genealogical link between Richard III and Michael Ibsen, says it is important that the King’s Catholic beliefs are recognized in the ceremonies.

Ashdown-Hill, who shares Richard III’s faith, has had a rosary, featuring the white Yorkist rose and a crucifix like one thought to have been owned by Richard III’s mother, made to be placed inside the coffin.

For Langley, the procession and celebrations are key to repairing past damage.

“The ethos and aim of the project was to give Richard what he didn’t get in 1485,” she says. “The reason we wanted to do that was to recognize what went on in the past but not repeat it, to make peace with history.”