Story highlights

Talks between the Syrian government going very slowly, U.N. mediator says

Talks go from face to face to separate corners on day two of Geneva negotiations

Government offer to evacuate women, children from Homs tough to take for opposition

They were in the same room, albeit not talking directly to each other. A success of sorts.

The Syrian government and opposition both agreed the atmosphere was calm – no shouting, no hostilities.

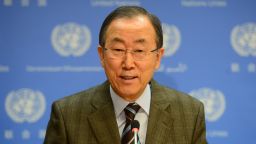

After two such meetings in Geneva Saturday, United Nations mediator Lakhdar Brahimi said that progress was moving very slowly, not even whole steps but half steps forward, he cautioned.

By Sunday the steps appeared to have gone in to reverse, the two sides no longer face to face but in separate rooms. Part of the separation later appeared to be the result of Mr. Brahimi’s mediating skill, allowing both sides, he said, to fully explore their positions with him individually.

To the uninitiated in the art of negotiation, it hardly seems positive, but there is much to learn in a close study of bringing two warring sides to peace.

No one ever thought that this early in the talks there would be goodwill between the two sides, but whatever mirage of common purpose holds them together is evidently too fragile to bear a frank exchange.

But here’s the rub: they are hooked in now, on the slippery slope of international diplomacy. Like the Hotel California, you can check in, but checking out is, well, not so easy.

Why? Neither side or its backers are going to want to be seen as the spoilers. Remember, if the talks fail, the first thing that will happen is that Mr. Brahimi writes a report and takes it to the U.N. The world will see, so each side is led to believe, exactly who is to blame.

The government doesn’t want even more international weight against it, and the opposition cannot afford to lose any international goodwill.

Unwittingly, perhaps, both sides have put themselves on this conveyor belt process that they do not control. To stop the machine, get off and save face will require more diplomatic skill than either side has shown to date.

They didn’t get into this blind. Getting here for both sides was never easy.

A year ago the opposition in its current form did not exist. Months of often strained and secret meetings, and molding in the hands of seasoned diplomats and Washington beltway advisers has finally brought shape to a group capable of going face to face with the Damascus government.

From the government’s point of view, why talk? They had upper hand on the battlefield, strong allies, Hezbollah and Iran providing fighters. Always the belief they could win. It took plenty of Russian arm-twisting to get them on board.

Even here in Geneva it’s hard to follow every twist and turn, keep up with the spin from all sides. What does stand out, however, is when one party stops spinning.

For the first few days it felt the opposition team was everywhere, keen to get in front of a camera and push their position, the government side not so much. Sunday that has all changed.

The opposition has put out one short statement. It speaks volumes. They are not happy.

The throttle of the peace conveyor was never in their control, and it has just lurched them to a very uncomfortable place. On Saturday they demanded an aid convoy for the old city of Homs. The government side feigned surprise, well-informed sources said, and refused to engage constructively on the issue, we were told.

Wise elder statesmen, skilled in the conveyance of the peace process, pontificated the regime was in an uncomfortable place, Russia would pressure them to compliance.

Neither the government nor the Russians could be seen to collapse the process and jump off the conveyor. It would hand the international community all the ammunition they need to turn the heat up on President Bashar al-Assad.

But what a difference a day makes. On Sunday, a counterattack by the government. Hopefully an aid convoy can get permission to get through, Mr. Brahimi said, but it was still in the works with the local governor, a process diplomats say that has failed many times before.

But there was an upside – Mr. Brahimi said the government would allow the women and children to leave and said other civilians could, too, if the opposition put their names on a list.

In essence, on day two of the talks, the government has asked the opposition to concede ground by evacuating citizens. It has put them between a rock and hard place. Absolutely outrageous is how one opposition advisor described it.

Try selling such a huge concession to an already skeptical base, try getting off the conveyor without looking like the bad guy. To everyone outside Syria, such an offer of safe passage, food and medicine for the women and children of Homs old city must look like a good deal.

But for the opposition, territory is everything. They have lost thousands of people in the fight to stay in their homes in Homs. Letting the women and children leave and handing over a list of men will look like clearing the way for a repeat of Srebrenica in Bosnia.

Serbs overran the town, taking it from U.N. peacekeepers in the summer of 1995. They’d demanded a list of names and sorted out the women and children as they closed in on the town. Seven thousand men and boys were slaughtered in cold blood.

For the opposition, such an offer from the government is no offer, but how can they turn this around without looking like the bad guys?

A roller conveyor on a roller coaster would be a better metaphor. We surely don’t have all the details.

But a process has begun, and neither side can or wants to get off yet, but how long can they hold on?