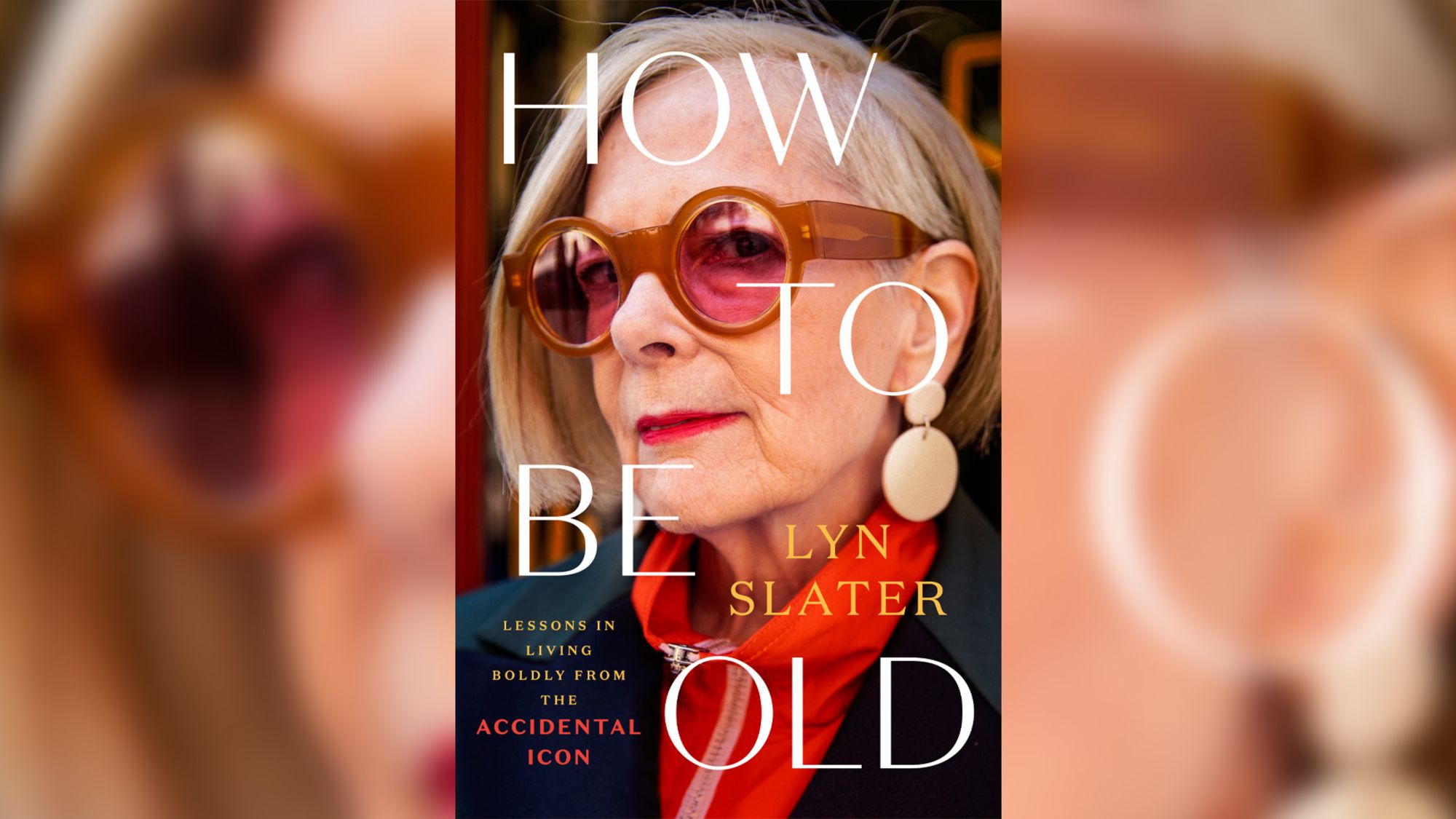

Editor’s Note: This piece is excerpted from Lyn Slater’s “How to Be Old: Lessons in Living Boldly from the Accidental Icon” with permission from Plume, imprint of Penguin Random House, LLC. © 2024 by Lyn Slater.

(CNN) — In the fall of 2019, I received an e-mail from a group of Parsons Fashion Design and Society MFA students who had been given the assignment to make a collection of clothes for “seniors,” as part of a course that involves creating designs that focus on disabled, plus-size, transgender and aging people. The students were divided into four teams, with each team charge to find a muse/collaborator within their respective category — to ensure primary research and a meaningful outcome. The students asked me for an interview, hoping that I might become their muse.

The students had gone around to senior centers, asking what older people want in their clothing. The answers — focused more on issues of fit, comfort and disguising signs of age — had discouraged them. Though these elements are important, the students seemed to want an aesthetic of age that could inspire them; they want to make old age high fashion, something beyond just function. (I think to myself that these fashionable young people want to design clothes they can see themselves in when they grow old.) But as we speak together, the fluid internal experience of aging, the memories held, and the desire to evoke them in what we wear are topics they become animated and excited about. Along with their tutors, these students and I begin our work together.

The process starts with me bringing in pieces from my wardrobe that hold meaning for me: There is the sleeveless A-line dress with pastel green and purple flowers that I wore under my doctoral gown the day I received my PhD; the Yohji Yamamoto suit I wore to my first day of class as a professor of social work and law. There is an oversized burnt-orange coat that covers me like a blanket, which I wear when I want to feel warm and safe, and a paisley Indian print dress I wore in the 1970s and now throw on when I go to the beach. Its colors are faded, and the thin cotton fabric is almost transparent after being worn for so many years — it seems on the brink of disintegration.

We have many conversations about the experiences attached to clothing during different periods of my life. We discuss how what I wear now, or want to wear, can allow experiences from different times of my life to be remembered. My young friends are curious about how I came to be empowered to wear what I want, to use clothes as devices to tell my personal stories and see style as being unique to every person.

I shared with them how my partner Calvin and I were recently walking around Harlem taking photos, and came upon the only remaining Kangol hat store in the world. I’m not a hat person at all, but I had a Kangol beret I used to wear backwards with overalls and a velvet shirt silk screened with Our Lady of Guadalupe when I was first exploring my creative self in the early 1990s, right after I left my marriage and was about to turn 40. (The shirt was a nod to my preoccupation with Frida Kahlo after a trip to Mexico, but I digress.)

The point is that when I walked into that store, I was transported back to that time. I heard the music and remember the galleries I went to, the classes I took and the books I read. So I try to explain to the students that it’s not that I need to wear exactly what I wore then, but clothes that evoke feelings and memories I felt. An approach to style that comes from our unique identities can convey a sense of time and place. And an article of clothing or an accessory contains history; it is a device that one can use to tell a story, one that is as different as the people who put it on.

The students and I speak a good deal about what it means to be old. Each week I arrive for a fitting of what they design, and the tutors give a critique. This becomes a conversation about how bodies change as we age.

The tutors and I observed how stereotypes and preconceived notions about being old found their way into the sessions, giving us the opportunity to question them. How the students’ initial designs cover me completely, for example, not acknowledging that I might still be a sexual being. By default, clothing for other adults is made to cover up their aging bodies. After this conversation, the textiles become more transparent — though they remain respectful.

Usually, garments made for aging bodies are not modern or representative because they don’t take into consideration the disconnect between the internal experiences of older people and the reality of their physical bodies. Many older people still feel youthful and engaged.

This results in the production of intricately crafted bespoke textiles, and clothes are not retro but modern — clothes that convey the sexuality and rebellious spirit that still inhabits me. The students create a dress made of crocheted Paisley prints in oranges and earth tones; a black coat with visible layers of varying tones and textures of grey and shaped like a cocoon that opens to reveal a transparent shirt; pants and a tunic with green and purple flowers caught in a spider web knit. These are pieces that turn remembering and aging into something that is modern and new — not just a retrospective view of a long life.

Each outfit created became a scene that performed a story of a life, a narrative that revealed some secrets about how to be old.

For the students, understanding the developing nature of identity as opportunity and deconstructing standardized notions of the “ideal” body are gifts they took away from the process. In their designs, they layered years of memory and meaning and saw aging in a way that was additive, not subtractive — something to look forward to.

The clothes the students designed for me made me feel understood. Working with younger people and solving this problem together reminds me of the utility of intergenerational collaboration, deep listening and mutual respect. Can you imagine, if we worked together so creatively on the multitude of issues we face in this current time, how we might change the way we think about being old or young?