Editor’s Note: W. Ralph Eubanks is the author of the new book “A Place Like Mississippi: A Journey Through a Real and Imagined Literary Landscape” (Timber Press), as well as “Ever Is a Long Time” and “The House at the End of the Road.” He is a visiting professor of English and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi. The views expressed here are his. View more opinion on CNN.

The South is America’s mirror, a region that reflects ideas about this country that many of us would rather not see reflected in our own visage. While not an ideological monolith, the South’s influence on American political culture is nonetheless larger than the region itself. As the historian Grace Elizabeth Hale has written, all Americans “must look clear-eyed and straight at ‘the South’ we all live in.”

With Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the case that overturned Roe v. Wade, Mississippi – and to an extent the South writ large – has set off a firestorm that has reached far beyond its borders. For years, many Americans have looked upon the way women’s right to abortion was being curtailed in Mississippi and the South as only something happening elsewhere, as if the policies being enacted in the South would never cross the Mason Dixon line (despite the realities unfolding in states such as Arizona, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, Idaho and Ohio).

Maisie Crow’s painfully moving 2016 documentary “Jackson” exposed the intimate details of the struggles of women in Mississippi to obtain access to abortion care, as well as the racial and religious undertones associated with the anti-abortion movement in the South. The “Pink House,” as Mississippi’s sole abortion clinic is known, came to symbolize the national struggle for abortion rights. Now not only is the Pink House closing, but so are other clinics like it all across the country.

The Dobbs case is not the first time ideas with roots in Mississippi spread far and wide. I would argue that because we as Americans have ignored 100 years of our history – from Reconstruction to the Civil Rights movement – we have difficulty recognizing the ways events in Southern history have had a broad impact on our lives today.

Bear in mind that when Mississippi adopted its 1890 constitution, that document included a poll tax and literacy tests designed to disenfranchise its newly enfranchised Black citizen. Enacting that constitution not only ended reconstruction in Mississippi but also became a model for the rest of the South. When the Supreme Court upheld Mississippi’s claim that its constitution was not discriminatory in Williams v. Mississippi in 1898, nearly every Southern state instituted measures to strip Black voting rights that should have been guaranteed by the 15th Amendment. Voter suppression statutes followed in South Carolina, Louisiana, North Carolina, Alabama, Virginia, Georgia, Oklahoma and more.

In its brief in Dobbs, Mississippi condemned Roe’s abortion rights protections and the 1992 Supreme Court decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which reaffirmed them, as “irreconcilable with constitutional text and ‘historical meaning.’” This originalist approach demands that the Constitution be interpreted based on its text and where necessary on its original meaning at the time it was enacted. Mississippi argued that the public in 1868 would have understood the 14th Amendment, known as one of the “Reconstruction Amendments,” to permit state restrictions on abortion to continue and the Supreme Court, like in 1898 with respect to the state’s voter suppression, agreed.

I find it audacious that Mississippi would evoke ideas of originalism in its interpretation of the 14th amendment, since it is the same amendment to the constitution that led to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision ending segregation in the South.

But with a conservative Supreme Court in charge, just as was the case in the 1898 case on its constitution, Mississippi’s strategy worked. What the framing of the reasoning for the Dobbs case reveals is that Mississippi and like-minded parts of the South are no longer a world unto themselves, with thinking and habits kept separate from the rest of the country. They are taking their ideas to a national stage. And now we all must confront them.

At one time Mississippi was what historian James Silver referred to as a “closed society,” one that sought to restrict ideas from outside its borders. Yet in his statement after the Supreme Court decision in Dobbs, Governor Tate Reeves noted that Mississippi helped lead the nation to overcome “one of the greatest injustices in the history of our country,” even claiming the decision has made the nation safer. Reeves continued in his statement, noting that Mississippi “seeks to be pro-life in every sense of the word – supporting mothers and children through policies of compassion and working to ensure that every baby has a forever family that loves them.”

Yet as most people know, Mississippi has one of the highest rates of infant mortality in the country. It has not expanded Medicaid, limiting access to healthcare to thousands of its citizens. As has been the case before in decisions on social policy, from the New Deal and the Great Society and today, the Black and the poor will bear the burdens of Mississippi’s policies.

When the decision to reverse Roe v. Wade was announced, I found myself thinking back to being a new Catholic convert in Mississippi in 1975, when I was just 18 years old. While I was taught the dogma of the Roman Catholic Church on abortion, I was also taught that Catholics were supporters of the expansion of welfare benefits and social services, so that this country would provide a social safety net that would enable everyone to live a dignified life.

What I was being taught was a consistent ethic of life, something that in the 1980s would be described by Cardinal Joseph Bernardin as the “seamless garment,” a term attributed to Catholic activist Eileen Egan and, in political terms, defined as an approach to issues with respect to human life that was not just concerned with the unborn but also the poor, the elderly, and others on the margins of society.

In Mississippi at the time, Catholics were suspect and placed on the social margins, not only because of their push for expanded social services, but also for the active involvement of many members of its clergy in the Civil Rights movement, including Bishop Joseph Brunini. Brunini was even under surveillance by Mississippi’s Sovereignty Commission, the state-sanctioned spy agency that operated from 1956 until 1973. The dominant Protestant majority – largely Southern Baptist – saw abortion as a Catholic issue. The seamless garment approach to life I was taught was a fringe, rather than mainstream, idea.

When I returned to Mississippi in 2016 after many years spent living elsewhere, things had changed significantly, both politically and socially. Ronald Reagan’s 1980 rally for “state’s rights” at the Neshoba County Fair, combined with the legacy of Richard Nixon’s “Southern strategy,” had led to the domination of the Republican Party. In a state that is 38% Black, Mississippi had also just gerrymandered itself into a Republican supermajority in the state legislature, effectively ending nearly a quarter century of biracial governance in the state. The politics of abortion rights played a leading role in state politics. As a friend put it, politics in Mississippi according to its Republican leaders were dominated by four issues: guns, God, gays and abortion.

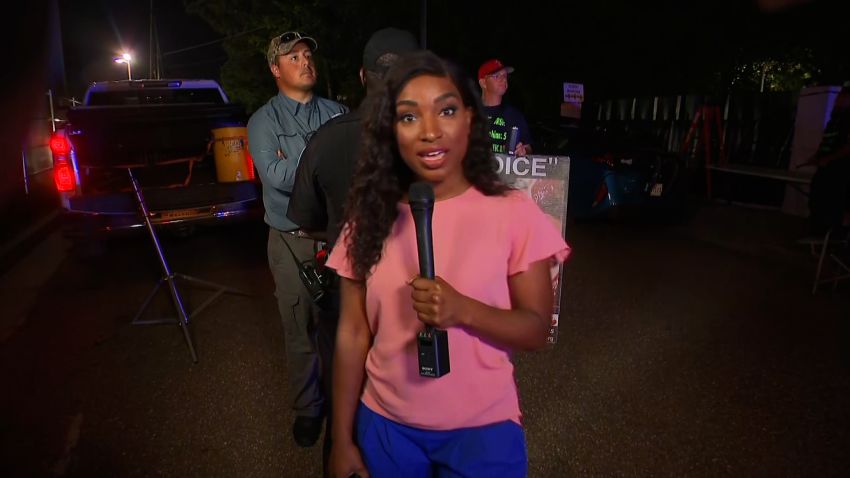

And the politics surrounding abortion were out in full view each time I entered Jackson’s Fondren neighborhood and encountered the protesters and counter-protesters outside the Pink House. Plus, no longer was I hearing preaching in Catholic churches encouraging a consistent ethic of life, one that included the living and the unborn. I regularly encountered an echo of Republican politics from the pulpit. One Sunday, when I heard a visiting pastor take a more nuanced approach to issues of human life in a sermon, I noticed that several of my fellow parishioners were visibly irritated.

Living in Mississippi again turned me into a pro-choice Catholic, which many of my co-religionists would argue is not Catholic at all. In the poorest state in the union – one in which a poor woman is more likely to survive an abortion than childbirth – I found myself more focused on the living than the unborn. I could not countenance the emotional violence I witnessed weekly in the constant shouting at women seeking abortions as having anything to do with Christian or Catholic doctrine. I grew so weary of the protests in Fondren that I stopped using my regular dry cleaners that was literally shouting distance from the clinic, just so I would not have to be exposed to vitriol that was nothing but belligerent and un-Christian.

What the end of Roe made me realize is that by setting the South apart and marginalizing it as a part of the American psyche, we as a society have for too long neglected the power and magnetism of the region’s cultural and political reach. Mississippi has influenced the rest of the country, whether we want to see that in our cultural mirrors or not. We are all historical beings, yet we often ignore the complicated parts of our history that serve as predictors of what is to come. Now we are witnessing how ideas nurtured in the bosom of the American South are taking a national stage. Mississippi is no longer a world unto itself. Whether we want to admit it or not, we all live in Mississippi now.