Editor’s Note: Jemar Tisby, PhD is the author of “The Color of Compromise” and he regularly writes about race, religion and culture in his newsletter, Footnotes. He is also cohost of the Pass the Mic podcast. The views expressed here are his own. Read more opinion on CNN.

As an elder millennial I grew up with Boomer generation Black parents whose horizons for “making it” in a White world included obtaining a college degree, getting a stable, professional-class job and having a 401K.

While it may sound tame today, those aspirations were actually quite ambitious for a group of people who lived through the civil rights movement – and who were born into a world where Black people couldn’t even eat at some restaurants.

But breaking racial barriers while raising their children to thrive often meant that Black parents of their generation felt they had to downplay or sidestep aspects of racism. Being too vociferous about racial injustices could jeopardize the scant progress they had made as individuals and as a people.

That’s why my parents taught us how to get along in White schools and workplaces in a way that wouldn’t draw too much negative attention. Even in the privacy of our own home, we didn’t explicitly talk much about race.

That doesn’t mean that I didn’t learn anything from them about how the world operates along racial lines – quite the opposite.

I remember my mom inadvertently teaching me to spot the other Black people in any given situation. She would say, “Oh, look! There’s some usses.” By which she meant there were other Black people like “us.”

I remember gathering as a family on Thursdays at 7 p.m. Central Time to watch a certain Black family – before all the disgusting allegations were revealed – and sharing an unspoken sense of pride at seeing an aspirational Black situation, even if it was made-for-TV.

But as a young Black male in America, I had to navigate all kinds of stereotypes and prejudices that no child should have to consider.

I remember wondering why a cop would bother tailing me and my racially and ethnically diverse group of friends in an arcade. What did he think – we were going to steal a whole arcade game?

There were the high school basketball games I attended as a fan where the other school, usually White and wealthy, called us the “ghetto” school.

And there was the isolation of being at a high school comprised mostly of Black and Latinx students but being in college prep courses where most of my classmates were White.

That feeling of isolation only increased when I went to a college that had an overwhelmingly White student body. For a couple of years, I was the only Black resident on my floor in the dorm. In most of my classes I was the only Black student.

Since my parents didn’t talk openly about race very often, I had to struggle through these situations with limited information and awareness. I wish I’d had more guidance, more wisdom, more companionship on my journey of developing my racial identity – one where I knew I wasn’t alone in feeling alone and where I could lovingly incorporate my Blackness into the fullness of my being instead of hiding or minimizing it.

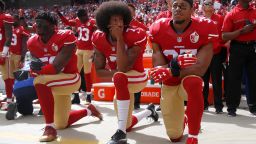

I think if a show like “Colin in Black & White” – Ava DuVernay and Colin Kaepernick’s new six-part Netflix docudrama about the 49ers quarterback’s youth and rise to prominence – had been out when I was in high school and college, I might have understood my racial identity more deeply and quickly.

Even though the protests of 2020 have largely subsided, they have left a remnant of adults and young people asking questions about the racial status quo, their place in a society still divided by the color line, and what they can do about it.

For young people struggling through what it means to be Black or bi-racial, “Colin in Black and White “offers engaging storytelling and social commentary with a dose of humor that makes the bitter pill of our racial reality a bit easier to swallow.

It raises important questions about what it means to be Black in a society that favors Whiteness and gives words to the inner struggles of trying to form a healthy self-image in contrast to the many negative portrayals of blackness that abound.

The series tackles some of the most important topics that Black kids and other kids of color face – dating, being stereotyped as threatening or angry, withstanding peer pressure, and more.

It does so with a sensitive eye toward complex racial dynamics and with a story based on someone who is fast building a legacy as a culture-shifting activist and social entrepreneur.

The young Kaepernick is played by Jaden Michael. Although only a teenager, he’s been acting most of his life and it shows. He plays the role with both innocence and depth. I had the opportunity to interview him on a podcast about how he approached playing a young Kaepernick and what he hopes viewers will learn from the show. From our interaction I can say that Jaden’s onscreen acting chops are only surpassed by his real-life insight and critical analysis about issues of race and justice.

He took a risk in taking on this role when so many view Kaepernick as a controversial figure. This kind of willingness to challenge himself and put his professional reputation on the line makes Jaden a young man whose career I’ll be watching with interest for years to come.

Mary-Louise Parker and Nick Offerman portray Kaepernick’s parents as well-meaning but largely clueless White adoptive parents of a Black son. They are at times affable and ignorant. One second you may think, “It wouldn’t be terrible to have a glass of wine with these folks” and the next you may feel like hurling both expletives and objects at the TV screen. In nearly every instance of covert or overt racism that Jaden’s Colin faces, his parents’ reaction seems to be to tell him to work harder. Parker and Offerman’s performances portray a complicated relationship, marked by parental failure to confront the policies, practices, systems and mindsets that make life so challenging even for someone as outstandingly talented as Kaepernick.

The series walks through Kaepernick’s high school years as a preternaturally talented multi-sport athlete. As his profile on the field grows, so do the obstacles he faces as a bi-racial Black child maneuvering in largely White settings.

I couldn’t relate at all to being an excellent athlete. I pretty much hated playing organized team sports in high school, but I could certainly empathize with the difficulties of growing up while Black.

In one episode, Kaepernick notices how differently he is treated from his White teammates when he and his family go to a hotel to stay for a baseball tournament.

White hotel employees confront him with all kinds of passive-aggressive messages that say, “We’re watching you, and you’ll be out of here the second we think you’ve stepped out of line.” The mere glimpse of an athletic Black youth is enough to raise suspicion and resentment.

“Colin in Black & White” is helpful for anyone, but it’s ideal for White people seeking to become more racially aware and for Black adolescents and teens who are searching for their own ways to become more conscious of their racialized place in the world.