If the blue hair wasn’t already a giveaway, Zandile Ndhlovu is channeling her inner mermaid.

A South African nine-to-fiver turned free diver, Ndhlovu says the ocean is the only place she’s felt a sense of belonging.

Yet the 33-year-old only discovered that feeling five years ago during an impulsive snorkel trip in Bali. “It was just the most incredible moment when I stopped panicking from thinking that I was drowning and just realizing the incredible world that was under there,” Ndhlovu tells CNN.

Fear gave way to excitement and soon she owned the sea – getting certified in everything from scuba diving to free diving – but she took note of its lack of diversity.

“When I got into this ocean space, for two to three years, I was always the only Black person on the boat,” Ndhlouvi says. “I had never seen another diver who looked like me.”

After she became South Africa’s first Black African free diving instructor, she says she felt a responsibility to make the ocean a more inclusive place.

Ndhlovu created The Black Mermaid Foundation, titled after her self-given nickname, with the intention of getting more people of color into the sea. “Where that (name) came from was just the realization that there were no Black mermaids exploring in the water the way that I was. And what followed was wanting to create representation around that,” she says.

Related: Photo series shows why African hair braiding is about more than just aesthetics

Through her foundation, Ndhlovu organizes ocean exploration programs for Black children across the country – many of whom have never seen the ocean.

“The foundation’s work is continuously taking (kids) out into the water and changing the stereotypes and the narratives that are attached to the ocean for us growing up,” she says.

A place of learned fear

As a young child, Ndhlovu was discouraged from going in the water past her knees.

“The ocean has been packaged as a fearful space in Black and Brown communities,” she says. “One, because our parents didn’t necessarily know how to swim, so if anything goes wrong, there’s nothing that anybody can do.”

Secondly, she says, is the enduring impact of the transatlantic slave trade off the coast of South Africa.

“When you look at slavery, people were thrown over the boats on these oceans … (that) trauma is passed down through history,” Ndhlovu says.

Kevin Dawson, professor of history at the University of California Merced, says this learned fear of water extends past South Africa’s shores.

“The slave trade was so traumatic that it caused this kind of generational, psychological trauma that discouraged swimming,” he says. “A number of slave ships end up sinking off the coast of South Africa, with almost everybody drowning. So that does get incorporated into these kinds of spiritual beliefs.”

Slave owners also used water as a form of torture, but Dawson says Black Africans’ apprehension towards water goes beyond the horrid tales of slavery.

When Christians first arrived in Africa, they stigmatized swimming due to its semi-nude nature, he tells CNN. This was further reinforced when colonial powers discouraged all forms of recreation in the 1800s.

During South Africa’s apartheid era, beginning in the 1950s, segregated beaches further perpetuated this trend, according to both Ndhlovu and Dawson.

“The Black beaches were always the least desirable beaches – (ones) that were polluted, that were receiving runoff; beaches prone to rip currents that would have made them more dangerous places to swim,” Dawson says.

Ndhlovu adds that many Black communities were pushed inland, far from the oceans, so they lack easy access – even today – to the ocean.

Turning the tides

It wasn’t always this way; Black Africans were historically considered to be the strongest swimmers and divers from the 1400s to 1800s, Dawson says.

Through Ndhlovu’s diving journey, she has tapped into her ancestors’ aquatic roots. And now, she wants others to follow suit.

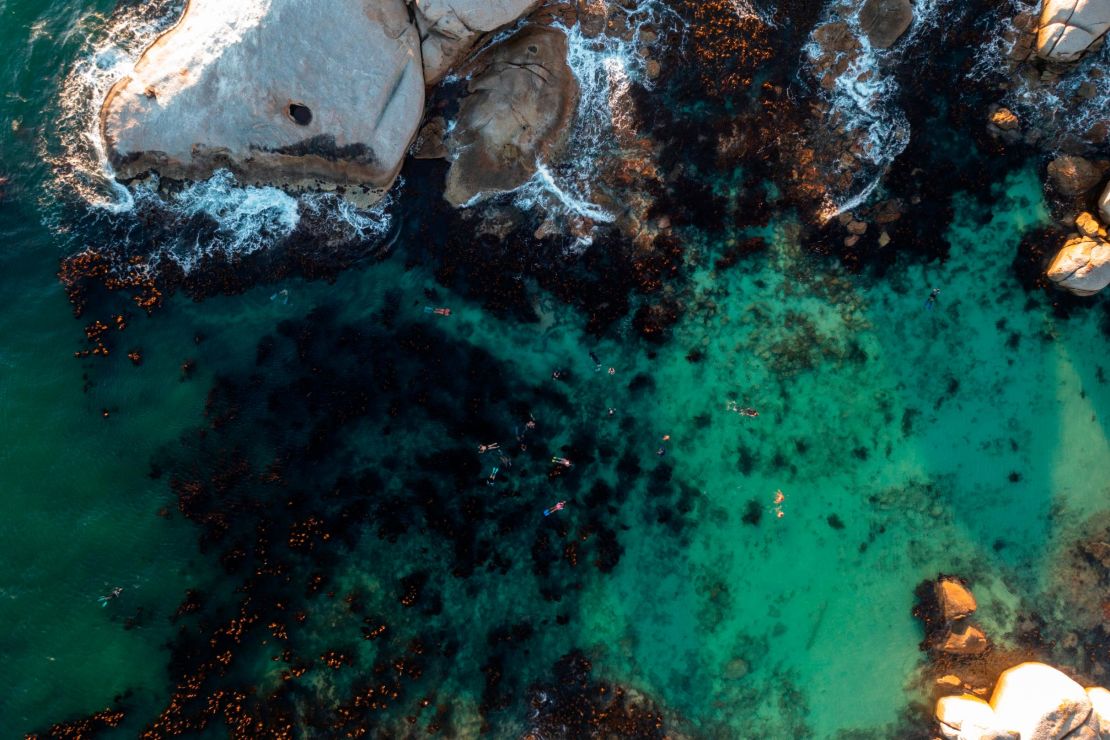

On any given weekend, Ndhlovu can be seen bringing groups of Black children to Windmill Beach in Cape Town to learn how to swim, watch penguins play, and discover the African Sea Forest – a vast underwater ecosystem.

“I want (kids) to realize that the ocean belongs to them as well and they should explore the careers that are possible at sea,” she says. “I always believe we can only care about something once we’ve seen it, and when we talk about ocean advocates, it starts here. It starts by getting into the water.”

Other foundations are also working to make the ocean more diverse across Africa and around the world. South African Surf company Mami Wata aims to cultivate African surf culture through representation.

In the US, Los Angeles-based Black Girls Surf is training girls how to surf in several countries including Ghana, Senegal, Brazil and Jamaica.

Representation is key in order to break down old stereotypes, Ndhlovu says, and so is access to swimming attire and equipment, which can be expensive.

Dawson agrees: “If we could just get people to donate bathing suits and wetsuits, I think that would fundamentally change Africans’ interaction with the water.”

While Ndhlovu is focusing on South Africa’s ocean waters for now, she has her sights set even bigger. “I want to see more diverse and inclusive ocean spaces,” she says. “(But) I want to see them everywhere. That’s my heart’s work and more than just the ocean space – everywhere.”

Watch the full episode of African Voices Changemakers featuring Ndhlovu’s story here.