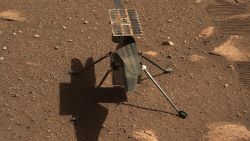

The Curiosity rover is heading for the hills as it continues to explore Mars, and the proverbial gold it’s looking for may surprise you: organic salts.

No, that’s not for your farm-to-table cooking. Organic salt is a key ingredient in the quest for evidence of life on planets beyond Earth.

The rover has been exploring Gale Crater, likely the site of an ancient lake, since 2012. It began ascending the 3-mile-high Mount Sharp, located at the center of the crater, in 2014.

The mission began with the goals of determining if conditions on Mars ever supported life as well as characterizing the Martian climate and geology. Curiosity has achieved most of what it was designed to do, but it’s now crossing into an interesting new phase: investigating a transition that occurred on Mars billions of years ago.

Evidence observed by robotic missions on Mars, as well as orbiters circling the red planet, have helped scientists determine that it was likely a warmer, wetter place about 4 billion years ago. That’s until some catalyst caused Mars to lose most of its atmosphere and become a frozen desert about 3 billion years ago.

Curiosity has spent much of its time over the last several years studying clay-rich rock layers on Mount Sharp. Now, it’s moving into a zone where the rocks grow salty, filled with sulfate minerals, according to Abigail Fraeman, Curiosity deputy project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The Curiosity mission is managed by staff at the lab, which is located in Pasadena, California.

The presence of clay rocks suggests that they formed when water was present on the planet. Sulfate minerals indicate that this water was evaporating or growing more acidic.

That means Curiosity is essentially crossing into a place where this transition from wet to dry occurred on Mars, so it can directly observe the effects of this ancient climate change.

A key clue

Organic salts left behind on Mars can not only provide evidence of water and its disappearance, but act as chemical footprints of ancient organic compounds. They are much more likely to survive on Mars than ancient molecules, which would have been much more fragile.

Curiosity has already found evidence of organic compounds on Mars. These could be indicators that ancient microbial life was once present, or they could have been formed through natural geologic processes.

Organic salts can add more heft to the idea that organic matter was once on Mars – but it also adds to the idea that Mars could still be habitable today. On Earth, organic salts can be used by some forms of life for energy.

“If we determine that there are organic salts concentrated anywhere on Mars, we’ll want to investigate those regions further, and ideally drill deeper below the surface where organic matter could be better preserved,” said James M. T. Lewis, an organic geochemist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, in a statement.

New research, published by Lewis and his team in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets in March suggests that these organic salts are on Mars – Curiosity just has to find them. And it’s not as easy as it sounds.

Even if these salts were lying directly on the Martian surface, they have been there for billions of years. The thin atmosphere on Mars means the salts have been subject to harsh radiation over time, which can break down organic matter.

The researchers have analyzed data from one of Curiosity’s onboard instruments called SAM, or the Sample Analysis at Mars. This ovenlike chemistry lab located inside the belly of the rover has indirectly indicated that organic salts are present on Mars.

What SAM can’t do is provide direct evidence. When the instrument heats up samples of Martian soil and rock collected by the rover, gases are released that can be used to determine the composition of the samples.

When organic salts are heated, they only release simple gases. These could be related to other components in Martian soil.

The data Curiosity sends back to Earth can be used by scientists to piece together the composition of rock and soil fragments on Mars, creating a larger picture of what the planet was like billions of years ago.

“We’re trying to unravel billions of years of organic chemistry, and in that organic record there could be the ultimate prize: evidence that life once existed on the Red Planet,” Lewis said.

For example, SAM helped researchers confirm the presence of organic molecules on Mars containing carbon, which is essential to life as we understand it.

“The fact that there’s organic matter preserved in 3-billion-year-old rocks, and we found it at the surface, is a very promising sign that we might be able to tap more information from better preserved samples below the surface,” said Jennifer L. Eigenbrode, an astrobiologist at NASA Goddard who worked on both the carbon study and the latest research with Lewis, in a statement.

The search for salt

Curiosity has an array of instruments stashed on board, and now researchers are looking to another one as a helpful tool in the search for salt.

The Chemistry and Mineralogy instrument, or CheMin, has not detected organic salts so far, but NASA scientists believe it could if there are enough of them present. Both SAM and CheMin will come into play as Curiosity crosses into new territory.

The SAM oven works by heating samples to 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (1,000 degrees Celsius) or higher. These scorching temperatures can break down molecules and releases gases.

Lewis and his team wanted to model what kinds of gases organic salts may give off if they made it into the SAM oven, so they ran an experiment on Earth that replicated Martian rocks. The scientists also simulated samples including perchlorates. These salts, which are common on Mars, include chlorine and oxygen. But scientists worry that if perchlorates are included in samples, they could interfere with the search for organic matter, given their composition.

“When heating Martian samples, there are many interactions that can happen between minerals and organic matter that could make it more difficult to draw conclusions from our experiments, so the work we’re doing is trying to pick apart those interactions so that scientists doing analyses on Mars can use this information,” Lewis said.

The team was able to show that CheMin could be used to detect organic salts. The instrument aims X-rays at Martian samples to determine their composition.

While the Perseverance rover, located about 2,300 miles (3,701 kilometers) away, doesn’t have any instruments that can detect organic salts, help will be on the way next year.

The European Space Agency’s ExoMars rover, launching in 2022, will be able to search for samples below the Martian surface because it can drill down 6.5 feet (2 meters) into the soil. It will carry an instrument developed at Goddard that can analyze soil chemistry.

And Perseverance is just the first step in a process that will eventually send back pristine Martian samples to Earth in the 2030s, which could not only include evidence of organic salts, but fossils belonging to ancient microbial life if it ever existed on Mars.