Story highlights

"Superbug" infections cause 2 million illnesses and 23,000 deaths each year in the U.S.

A CDC report calls on health care centers to take improved steps to reduce the spread

The CDC recommends health care facilities "optimize" infection control measures

An estimated 37,000 people could die in the next five years from antibiotic-resistant “superbugs” if health care centers don’t work together to prevent infections, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says in a report released Tuesday.

“We need to think as a community when it comes to combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria,” said Dr. John Jernigan, who contributed to the new report and is director of the Office of HAI Prevention Research and Evaluation of the CDC’s Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion. “Health care facilities and public health departments need to work as a team.”

The CDC used mathematical modeling to calculate that 619,000 infections and 37,000 deaths could be prevented in the next five years from antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Prevention is possible, the report explains, if hospitals improve how they control infections and a system is set up that helps hospitals act cooperatively to send alerts when infections crop up.

Currently, many hospitals work independently to control patient infections and don’t report outbreaks to local or state health departments. The CDC report says this self-reliant approach isn’t working, and patients are getting sick and dying as a result. This is especially worrisome because patients can harbor drug-resistant bacteria on their skin or in their body without showing signs or symptoms.

Related: Obama battles ‘superbugs’ with national plan

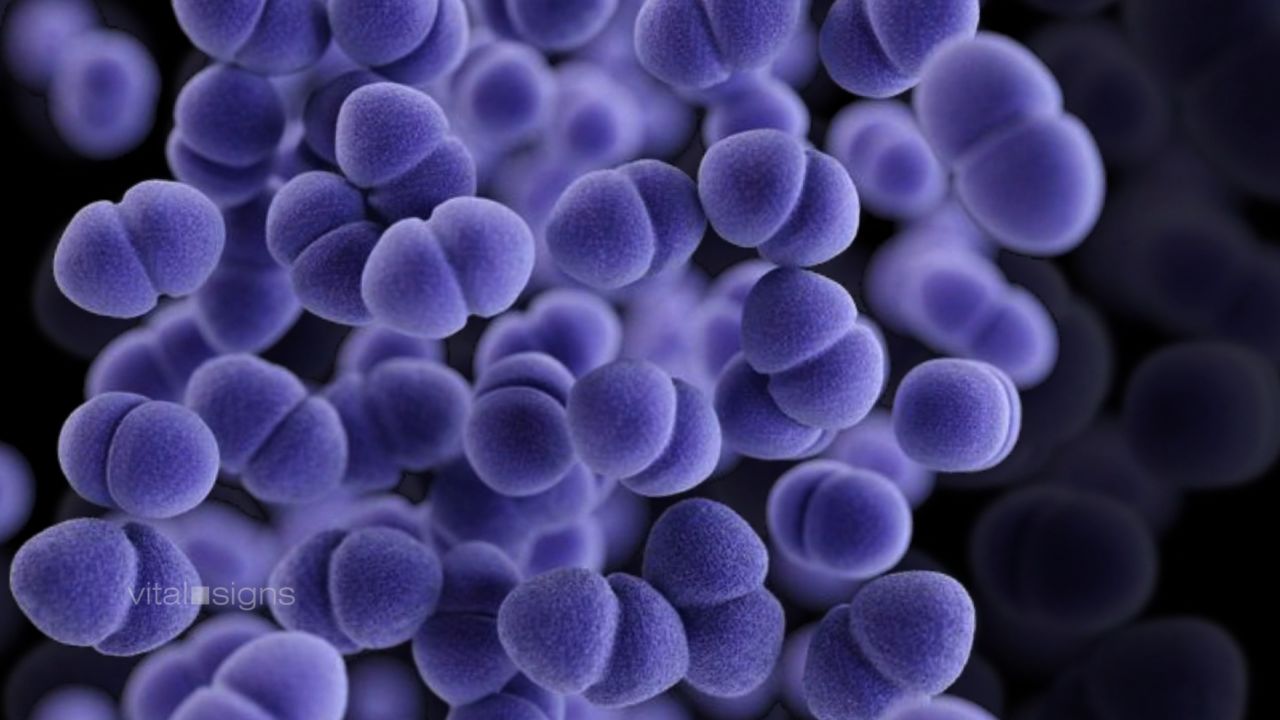

The team of researchers looked at the impact of four types of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections: CRE (carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae), multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, invasive MRSA (Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), and CDIs (Clostridium difficile infections).

The first line of treatment is antibiotics, drugs designed to kill bacteria. These medicines can save lives when used correctly. But when doctors overprescribe them, incorrectly use them to treat viruses, or when patients don’t finish the entire course, the treatment can backfire as bacteria adapt and become resistant to antibiotics.

As a result, when a person is infected with a so-called “superbug,” it cannot be controlled with antibiotics, putting the patient at risk of death. Every year in the United States, about 2 million illnesses and 23,000 deaths result from superbug infections, according to the CDC.

Related: Drug-resistant bacteria linked to two deaths at UCLA hospital

The CDC report also recommends doctors practice “antimicrobial stewardship,” the responsible use of antibiotics.

“Antibiotic stewardship comes down to using the right kind of antibiotics, at the right dose, for the right reason, ” Dr. Jesse T. Jacob, assistant professor at Emory University School of Medicine says, adding that doctors aim to “give antibiotics long enough to treat the infection, but not so long that side effects occur.”

“Even if one health care facility is following the recommended infection control, they need to remember they are impacted by what facilities around them are doing as well,” says Dr. John Jernigan, who contributed to the new report and is the director of the Office of HAI Prevention Research and Evaluation of the CDC’s Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion.

Patients should tell their doctor if they’ve been hospitalized in another facility or country in case they have unknowingly come into contact with antibiotic-resitant bacteria, Jernigan said. He also advised patients to practice good hand-washing practices and insist that their health care providers do the same.

This isn’t the first time health experts have sounded the alarm about the threat posed by misuse of antibiotics. Bacteria have been mutating to outsmart antibiotics since the first medical antibiotic, penicillin, was mass-produced in 1944. However, it wasn’t until the 1960s that bacterial resistance picked up speed.

“Clearly resistance is going the wrong way,” said Jacob. “It’s a big problem now. At times we don’t have the antibiotics we need to treat infections.”

What’s next? It’s up to Congress to provide the resources and funding public health departments need to reduce the number of antibiotic-resistant infections, said CDC Director Dr. Tom Frieden during a telebriefing Tuesday. He reiterated: “We are low in resources to roll (these changes) out rapidly.”