Story highlights

Gunmen storm satirical magazine's office in Paris, officials say

Charlie Hebdo has courted controversy before with satirical takes on religious extremism

Magazine's offices were burned down in 2011 after it published a cartoon depicting the Prophet Mohammed

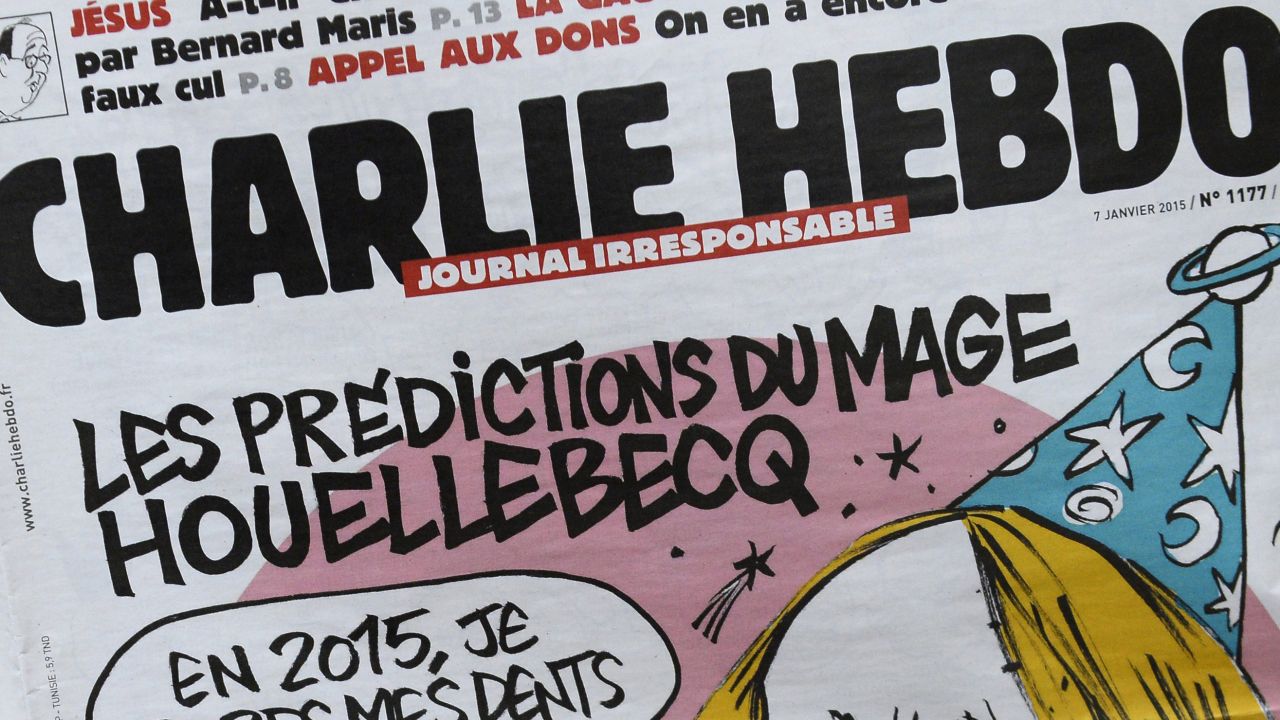

Charlie Hebdo, the French magazine targeted by gunmen who killed journalists and police in a brazen lunchtime attack Wednesday, is no stranger to controversy.

The Paris-based weekly satirical publication, which was founded in 1970, became famous for its risqué cartoons and daring takedowns of politicians, public figures and religious symbols of all faiths.

And although the motive behind Wednesday’s massacre is not yet clear, Charlie Hebdo’s notorious cartoons satirizing the Prophet Mohammed in recent years have angered some Muslims and made it a target for attacks.

“Everybody knows them when you work in journalism,” said Marie Turcan, a journalist who was just 200 meters from Charlie Hebdo’s central Paris office when the shooting began. “They have marked French journalism forever with their drawings and their cover stories.”

A reputation for controversy

In November 2011 Charlie Hebdo’s office was burned down on the same day the magazine was due to release an issue with a cover that appeared to poke fun at Islamic law. The cover cartoon depicted a bearded and turbaned cartoon figure of the Prophet Mohammed with a bubble saying, “100 lashes if you’re not dying of laughter.”

In September 2012, despite the ongoing global furor over the anti-Islam film “Innocence of Muslims,” the magazine published an issue featuring a cartoon that appeared to depict a naked Mohammed, along with a cover that appeared to depict Mohammed being pushed in a wheelchair by an Orthodox Jew. French and American officials expressed dismay with the decision, and France closed embassies and schools in about 20 countries temporarily as a precaution.

Charlie Hebdo journalist Laurent Leger defended the magazine at the time, saying the cartoons were not intended to provoke anger or violence.

“The aim is to laugh,” Leger told BFM-TV in 2012. “We want to laugh at the extremists – every extremist. They can be Muslim, Jewish, Catholic. Everyone can be religious, but extremist thoughts and acts we cannot accept.”

“In France, we always have the right to write and draw. And if some people are not happy with this, they can sue us and we can defend ourselves. That’s democracy,” Leger said. “You don’t throw bombs, you discuss, you debate. But you don’t act violently. We have to stand and resist pressure from extremism.”

Massacre at editorial meeting

Charlie Hebdo’s last tweet before Wednesday’s attack featured a cartoon of ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi seemingly sending out his wishes for the new year with the words “And, above all, health.”

Police surveillance had reportedly been fairly tight around the magazine’s office until recently, and there had been 24-hour surveillance of the premises before that, according to CNN’s Jim Bittermann in Paris. Bittermann said the staff of Charlie Hebdo, which publishes weekly on Wednesday, were in their lunchtime editorial meeting when the gunmen stormed the building.

Among the dead are editor Stephane “Charb” Charbonnier along with Georges Wolinski, Jean “Cabu” Cabut and Bernard Verlhac, known as “Tignous” – some of France’s “most talented cartoonists,” according to French journalist Agnes C. Poirier.

Christopher Dickey, the Paris-based foreign editor of The Daily Beast, said Charlie Hebdo is a small publication that packs a big punch.

“It doesn’t have a huge readership, but it has always had a very controversial approach to the news,” Dickey told CNN. “To see it silenced this way, especially after it survived a firebombing of its headquarters three years ago, is really reprehensible.”

Thousands of people took to social media in the attack’s aftermath to express solidarity with Charlie Hebdo, posting images with the words “Je Suis Charlie” in white on a black background, or paying tributes to the magazine on Twitter using the #JeSuisCharlie hashtag.

Some considered cartoons blasphemous

Any depiction of Islam’s prophet is considered blasphemy by many Muslims. France has the largest Muslim population in Western Europe, with an estimated 4.7 million followers of the faith.

France, which is known for its stark separation of church and state, angered some Muslims in 2011 when it banned full-face Islamic veils like the burqa, claiming they were degrading and a security risk.

Charlie Hebdo is far from the only publication whose depiction of Mohammed sparked controversy. Newspapers in Norway and Denmark prompted furious demonstrations around the world in 2005 when they ran Mohammed cartoons.

Several cartoonists were attacked in the fallout of that controversy. Sweden’s Lars Vilks got death threats after drawing Mohammed with the body of a dog. And a man tried to break into Danish cartoonist Kurt Westergaard’s house after he portrayed Mohammed wearing a turban shaped like a bomb.

Hollande reacts

On Wednesday, French President Francois Hollande reacted to the news: “France is today facing a shock, the shock a of a terror attack, because this is a terrorist attack without a doubt, against a publication that was threatened several times and that was protected.”

“In these moments we have to form a block to show we are a united country. We know how to react appropriately, with firmness, but always with the concern for national unity.”