To many, these are not matters for debate.

If historical figures embraced hate or violence, it doesn’t matter that they were great singers, innovators or wartime strategists, nor that they had changes of heart later in life.

“In many cases, preserving history was not the true goal of these displays,” former Southern Poverty Law Center president Richard Cohen said of the center’s 2016 report that found at least 1,500 US government-backed tributes to the Confederacy.

“Rather, many of them were part of an effort to glorify a cause that was manifestly unjust – a cause that has been whitewashed by revisionist propaganda that began almost as soon as the Civil War ended. Other displays were intended as acts of defiance by white supremacists opposed to equality for African Americans during the civil rights movement.”

To say the hate or violence was a product of the times may sound fair, but protesters today are products of theirs. Cancel culture, with its shortcomings, insists that Christopher Columbus was no explorer but rather the most brutal of colonizers, and Robert Lee was no general; he was a slave-owning traitor who led thousands to their deaths in a rebellion to defend the subjugation of blacks.

Here are some other unforgivable acts:

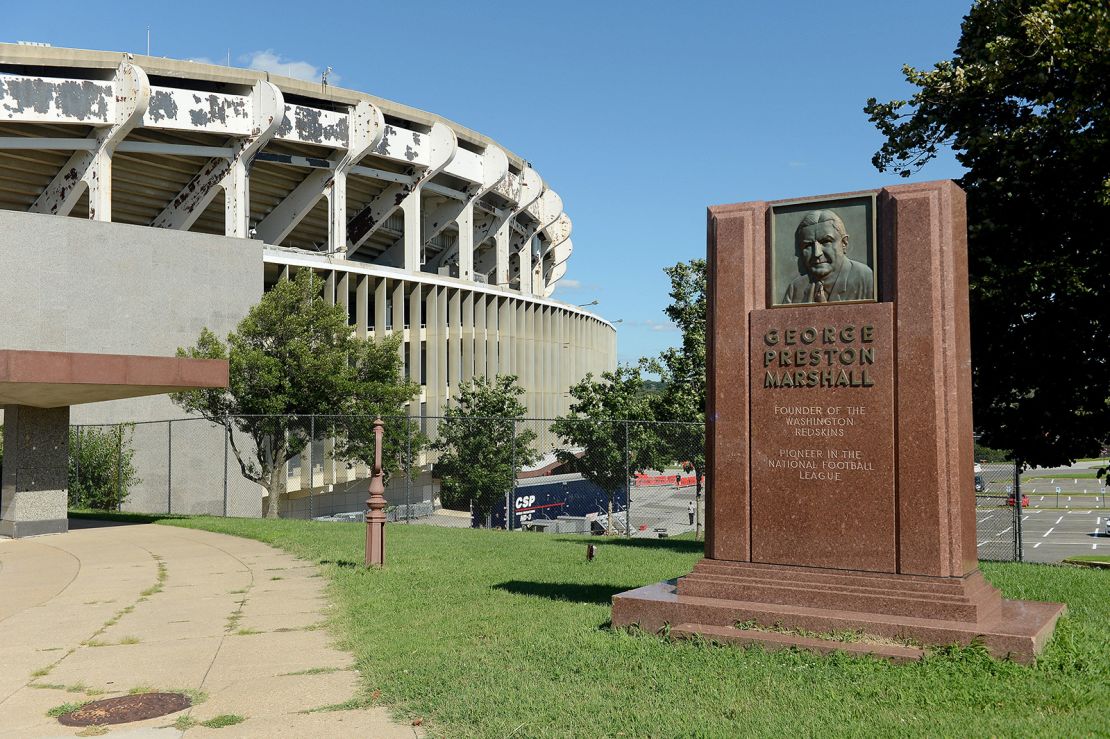

George Preston Marshall

Think the football team in the nation’s capital has a controversial name? You should learn about its founder.

In 1961, the Washington Redskins were the only of 14 NFL squads that hadn’t integrated. Interior Secretary Stewart Udall confronted Marshall, explaining then-DC Stadium was on national park land and the team might not keep its lease if Marshall didn’t sign a black player.

The powerful Marshall replied that he wanted to debate the issue with President John F. Kennedy. Marshall considered his “the team of the South” – the team song at the time included the line, “Fight for old Dixie” – and Marshall had said, “We’ll start signing Negroes when the Harlem Globetrotters start signing whites.”

Status: A monument honoring Marshall stands outside what is now Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium.

Source: The Washington Post

Henry Benning

Benning was no garden-variety Confederate general. He was a champion of its darkest aims, years before the Civil War began.

He “was such an enthusiast for slavery that as early as 1849 he argued for the dissolution of the Union and the formation of a Southern slavocracy. Fort Benning’s physical location, on former Native American territory that became the site of a plantation, itself illustrates the turbulent layers beneath the American landscape,” retired Army Gen. David Petraeus wrote in an essay.

Status: Fort Benning near Columbus, Georgia, bears his name.

Source: Petraeus

Roger Taney

Six years before the Emancipation Proclamation, the US Supreme Court chief justice wrote in Dred Scott v. Sandford that no slave or descendant of slaves – freed or not – could be “acknowledged as a part of the people.” Slaves were property, he ruled, and thus, the Fifth Amendment barred courts from freeing them.

The 1857 decision stood 11 years, until the 14th Amendment was passed in 1868. Scott died in 1858.

Taney wrote of slaves, “We think they are not, and that they are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution.”

“On the contrary,” he continued, “they were at that time considered as a subordinate and inferior class of beings, who had been subjugated by the dominant race, and, whether emancipated or not, yet remained subject to their authority, and had no rights or privileges but such as those who held the power and the Government might choose to grant them.”

Status: Statues of Taney have been removed from the Maryland State House and from Baltimore’s Mount Vernon neighborhood. A statue of Dred and Harriet Scott stands in St. Louis.

Source: Dred Scott v. Sandford

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Before his “wizardry” with a saddle made him the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan – of which he was one of its earliest members – Bedford’s men exacted one of the more disturbing massacres in American military history.

After successfully attacking Fort Pillow, manned by hundreds of black and white Union soldiers in Henning, Tennessee, Bedford’s troops continued the “slaughter” after many troops surrendered, according to Sgt. Achilles Clark’s letter to his sisters in 1864.

“Words cannot describe the scene. The poor deluded negroes would run up to our men, fall upon their knees and with uplifted hands scream for mercy but they were ordered to their feet and then shot down. The white men fared but little better. Their fort turned out to be a great slaughter pen,” he wrote.

“I with several others tried to stop the butchery and at one time had partially succeeded, but Gen. Forrest ordered them shot down like dogs. and the carnage continued. Finally our men became sick of blood and the firing ceased.”

Status: A Memphis statue was removed, a park bearing his name was rechristened and his remains will be relocated, but a bust in the Tennessee Capitol still stands, as does a memorial tablet in Murfreesboro. He is honored in numerous locations throughout the South, most notably in Tennessee, birthplace of both Forrest and the Klan. A 25-foot-high statue of Forrest sits on private land in Nashville.

Source: Clark’s letter, via the Gilder Lehrman Institute

Thomas Parran Jr.

Under Surgeon General Parran’s leadership, the US Public Health Service undertook a study of 600 black men in Alabama, almost two-thirds of them suffering from syphilis, and told the men they were being treated for “bad blood.” It became known as the Tuskegee syphilis experiment.

Though blame can be divvied up, Parran wrote in 1932 of Macon County, Alabama, where Tuskegee is located: “If one wished to study the natural history of syphilis in the Negro race uninfluenced by treatment, this county would be an ideal location for such a study.”

Even when penicillin emerged as a treatment 15 years into the “study,” the men received only free exams, meals and burial insurance, and “although originally projected to last 6 months, the study actually went on for 40 years,” the CDC says.

Status: Parran’s name has been removed from the University of Pittsburgh’s Graduate School of Public Health.

Source: CDC, The Philadelphia Inquirer

Juan de Oñate

A conquistador and the first Spanish governor of New Mexico, Oñate sought to colonize the Acoma Pueblo, and when spiritual leader Zutacapan learned of the plans, a battle ensued, killing a dozen of Oñate’s men, including his nephew.

Oñate responded by exacting a massacre, leaving 800 dead, 300 of them women and children. Twenty-four men older than 25 had their right feet chopped off, and were enslaved for 20 years, along with many other Acoma, some as young as 12.

Status: Albuquerque officials took down a statue of Oñate after a protest turned violent in June. Protesters chopped off the foot of Onate’s statue in Alcalde, New Mexico, in 1998. Another statue resides at El Paso’s international airport.

Source: Institute of American Indian Arts, CNN affiliates KVIA and KRQE

Robert Byrd

No one served in the US Senate longer than Byrd, but before he kicked off his political career in the West Virginia Legislature, he wrote a letter to Sen. Ted Bilbo, a Mississippi segregationist, decrying President Harry Truman’s efforts to integrate the military. He’d rather see his country crumble, he wrote, than fight “with a negro by my side.”

“Rather I should die a thousand times, and see Old Glory trampled in the dirt never to rise again, than to see this beloved land of ours become degraded by race mongrels, a throwback to the blackest specimen from the wilds,” he wrote.

Perhaps this isn’t surprising from a onetime exalted cyclops of the Ku Klux Klan. Even after he supposedly renounced the Klan, he filibustered the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and was the only senator who voted against the confirmations of the country’s two black Supreme Court justices, Thurgood Marshall and Clarence Thomas.

In his later years, he referred to same-sex marriage as “aberrant behavior” and told an interviewer in 2001, “There are white n***ers. I’ve seen a lot of white n***ers in my time.”

Status: Dozens of buildings, several roads and a bridge in West Virginia bear his name.

Source: The Washington Post, CNN

Edmund Pettus

Historians say state leaders meant to send a message in 1940 when they named Selma’s bridge over the Alabama River after a top leader in the South’s effort to secede from the Union.

“It had been named after a Civil War General and Grand Dragon of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan who served in the United States Senate from 1897 until his death in 1907. He was the last Confederate General to serve in the Senate,” the Federal Highway Administration says.

In 1965, the bridge became the site of “Bloody Sunday,” a pivotal episode in the civil rights movement, where police and a posse attacked unarmed protesters, badly injuring dozens, including protest leaders Amelia Boynton and now-US Rep. John Lewis.

Status: The bridge bears Pettus’ name.

Source: Smithsonian, FHWA

Kate Smith

She was known as the First Lady of Radio, but the Philadelphia Flyers and New York Yankees no longer play her rendition of “God Bless America” at their games.

The controversy stems from two songs in her catalog: “Pickaninny Heaven,” in which she sang, “Great big watermelons roll around and get in your way in the pickaninny heaven,” and another that included the lyrics, “Someone had to pick the cotton, someone had to pick the corn / Someone had to slave and be able to sing, that’s why darkies were born.”

Status: A statue of Smith was removed from outside the Flyers’ Wells Fargo Center last year.

Source: Smithsonian, CNN

John C. Calhoun

Among his many positions in the federal government, Calhoun served as John Quincy Adams’ and Andrew Jackson’s vice president, and throughout his time in politics, he described black people as inferior and went beyond his Southern cohorts who described slavery as “a necessary evil.”

“I hold it to be a good, as it has thus far proved itself to be to both (races), and will continue to prove so if not disturbed by the fell spirit of abolition. I appeal to facts. Never before has the black race of Central Africa, from the dawn of history to the present day, attained a condition so civilized and so improved, not only physically, but morally and intellectually,” he wrote as a slave-owning senator in 1837.

“I hold that in the present state of civilization, where two races of different origin, and distinguished by color, and other physical differences, as well as intellectual, are brought together, the relation now existing in the slaveholding States between the two, is, instead of an evil, a good – a positive good.”

Status: Clemson University removed Calhoun’s name from its honors college in June, and Yale University in 2017 renamed its Calhoun College for mathematician Rear Adm. Grace Murray Hopper. A monument of Calhoun atop a pillar stands in downtown Charleston, South Carolina.

Source: Clemson University