Never has there been a more humbling year for a reporter.

This was a year when predictions were shattered, polls discredited, facts eschewed and rationality dismissed. “Populism” spread like wildfire across the West, thumbing its nose at elites seen by so many voters as complacent and self-serving.

The liberal international order built after 1945, triumphant when the Berlin Wall came down, suddenly looked very vulnerable as free trade came under attack, the “ever closer” European Union began to shred and an authoritarian Russia reasserted itself.

Of course the seeds were sown long before 2016: the consequences of globalization, mass migration, growing resentment about inequality, diminishing trust in political institutions – their effects turbo-charged by social media and fake news. We just never imagined them bearing such bitter fruit so suddenly.

The day before the Britain’s vote on its membership of the European Union – the first of 2016’s profound shocks – I was sitting across from a Texan on a Eurostar train from Brussels to London. He owned a small, successful business and was traveling around Europe with his family. But he was more excited about witnessing Brexit playing out than visiting Buckingham Palace.

“I really hope Britain gets its independence back,” he began. He spoke in soaring terms about sovereignty, freedom from the shackles of political correctness and globalization, which was why he said he would support Trump for President.

“I don’t really like Trump that much,” he admitted. But he was tired of having to apologize for being a white American, tired of his kids’ universities teaching them their country was evil, and tired of being told his beliefs were narrow-minded and offensive.

READ MORE: Photo that captures 2016’s political tsunamis

Little faith in politicians

It was a refrain I would hear again and again, “I don’t really like Donald Trump but…” followed by a laundry list of grievances.

In places like Thomaston, Georgia, Trump’s call found a ready audience. Until the 1990s, about 4,000 people earned a wage in its textile mills. Then the work went overseas, to Guatemala and Bangladesh, and good paying jobs became hard to find. Most of the redbrick mills in this town of 10,000 people are silent now, shrouded in weeds.

Mayor John ‘JD’ Stallings grew up in the town, and remembers fondly when the stores on Main Street would advance credit on the promise of the next paycheck. Now there aren’t many stores on Main Street; people go to the big Walmart on the edge of town to save bucks (and buy cheap, foreign-produced goods). And there are fewer pay checks.

For a generation, Thomaston has voted Republican, but Stallings said this election was different. Trump mobilized people because he promised jobs and rejected deals like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which he said had “destroyed our country as we know it.” In Thomaston, that message resonated.

US Vice-President Joe Biden has spoken of people who felt “left behind,” who were unable to assure their children that things would be OK and who had little faith in politicians to fix them. While the rich were better-off than ever and lived longer, these people did not. Between 2001 and 2014, the life expectancy of the richest 5% of Americans increased by roughly three years. For the poorest 5%, there was no increase.

That mood, on both sides of the Atlantic, was fed by a sense that governments were “not looking after their own.” The establishment – it seemed to a wide swathe of voters – was in league with big banks and foreign governments, infatuated by political correctness. It fussed over gay marriage and transgender bathrooms (“Not much of an issue here,” as Mayor Stallings dismissed it) and bent over backwards to accommodate refugees.

READ MORE: Wake up! Trump isn’t a real populist

Anti-factual ideology

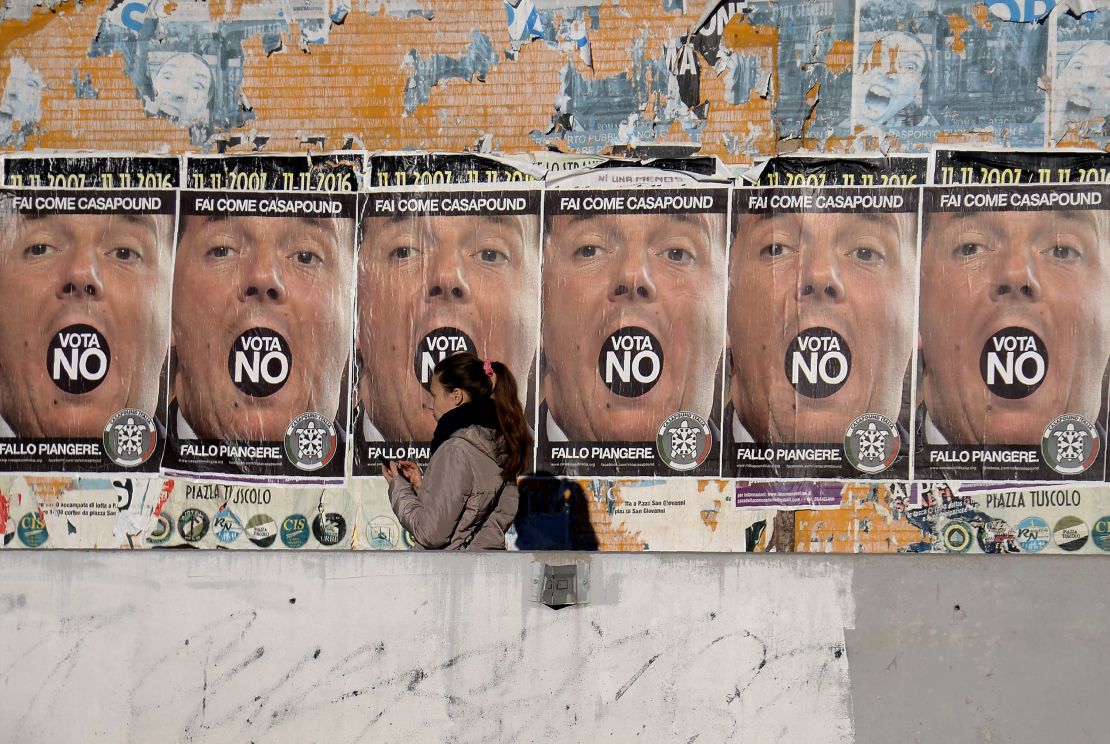

This anger was neither “right” nor “left” but “anti.” It was mobilized and exploited by outlier politicians like Trump, Nigel Farage of UKIP in England and Beppe Grillo, the leader of the anti-establishment Five Star Movement in Italy. Dubbed as populists, they used unusually blunt language, set out complex issues in simple terms and sided with the underdog.

“I love the poorly educated,” exclaimed Trump. His margin of victory among whites without a college degree was the largest of any candidate since 1980. Welcoming Trump’s victory, Grillo said he had “sent an F-U to everyone: Freemasons, big banking groups, the Chinese.”

The sense of indignant fury, which has fueled this movement has often been challenging to cover as a reporter. It is not an ideology that can be challenged with facts or tempered with reason. It is emphatically anti-factual, anti-intellectual, anti-science. But it has held up to the light an inherent weakness of liberalism, which is open, encourages dissent and runs the risk of being usurped by a less tolerant and inclusive “-ism.”

So does the “establishment” have to adapt by stealing at least some of the clothes of this movement? It’s a question many European leaders are asking themselves.

“When voters move in another direction,” Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte told the Financial Times last week, “it means the mainstream parties have to be more successful in showing we can solve these problems.”

Rutte faces that challenge in elections next March, with the xenophobic and anti-EU Freedom Party leading the polls. Rutte’s government has introduced new rules insisting refugees have a “personal responsibility to integrate, to learn the language and find work.”

In Germany, Angela Merkel has just demanded a ban on the full-face veil or burqa “wherever legally possible” ahead of a general election in 2017. She too faces an insurgent right-wing party, the Alternative for Germany.

And in France, Francois Fillon has cast himself as the “retro” candidate, celebrating the “values” of provincial middle-class Catholic citizens and complaining that the history books in schools “do not reflect what it is to be French.”

Polls suggest Fillon will go head-to-head with the leader of the National Front, Marine Le Pen, in next year’s Presidential election: the right against the far-right.

READ MORE: Trump, Brexit and populism ‘not all the same’

‘Democracy’ a dirty word

And then there is Russia or more accurately Vladimir Putin. In 2011, when the Syrian uprising began, no-one I met in Syria talked much about Russia. People wanted to know if President Obama would help them or Angela Merkel would support a no-fly zone? They discussed concepts like democracy and self-determination into the early hours of the morning.

Traveling through rebel-held Aleppo in the spring of this year, I found President Obama and the US were rarely spoken about, except with a cluck of bitter disappointment and derision. Democracy was now a dirty word. And Europe? Not even a mention.

But I was asked constantly about Putin, as Russian jets pounded the region in support of the Assad regime. What was his goal in Syria? Who was secretly backing the Russians? The people I met could not fathom why he had a free hand to bomb their country.

The Obama doctrine, sometimes dubbed “leading from behind,” for its reliance on regional partners and its cautious approach to the use of American force, was the polar opposite of Putin’s ruthless opportunism. Europe said much but did little, Putin the reverse. And he has found admirers among those challenging conventional wisdom in Europe and the US.

In a few weeks, the Russian leader will have a US counterpart apparently at ease with his worldview. “Leading from behind” may become “Let them get on with it.” And polls show that would be just fine with about 60% of Americans.

In Merkel’s words: “We are faced with a world, especially after the US election, that needs to reorder itself, with regard to NATO and the relationship with Russia.”

But while President Putin is mortal, forces like globalization, automation, artificial intelligence and the explosive expansion of social media are here to stay. Merkel and President Obama declared that “the future is already happening and there will not be a return to a world before globalization.”

READ MORE: Populism in Europe – a visual guide

Course correction or radical shift?

Just don’t expect everyone to go quietly. A Pew Research Center poll this year found that half of Americans believe global economic engagement is “a bad thing” because it lowers wages.

Trump framed “Make America Great Again” in terms that rejected globalization.

The town of Thomaston is a case in point. It has begun to win back some jobs – in printing, with a bio-refinery and with the resurrection of two of its textile mills. The work, for those who have it, pays well. But it’s highly automated: the machines making towels for JW Marriott Hotels are controlled by computers. Average incomes have fallen there this century – from $18,193 per capita in 2000 to $13,925 in 2013.

From time immemorial, financial markets have been prone to bubbles. They expand fast, bringing a burst of prosperity and optimism. When that becomes irrational exuberance they are prone to burst. Anxiety and retreat follow - it’s the markets’ cyclical way of correcting themselves when the sums don’t add up.

Maybe our democracies are mimicking the markets – the rich were getting too rich, technology too complex, elites too smug. A “course correction” was overdue. But maybe something more profound – challenging the very essence of the liberal order – is afoot.

READ MORE: Liberals need to grow a spine in 2017

Perhaps 2017 will offer the first clues on how open societies that stand for tolerance, free trade and diversity can reinvent themselves. Or maybe it will herald the beginning of a more chauvinistic era, one in which the American example as the “indispensable nation” will continue to fray, while the raw exercise of power pays off.

We are not the first generation to be on the cusp of such change.

Traveling through England in 1835, as the country grappled with industrialization and the clamor for representation, the French philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville wrote that “to live in freedom one must grow used to a life full of agitation, change and danger.”

CNN’s Tim Lister contributed to this report.