On May 6, 1882, President Chester Arthur signed a law that reshaped America. More than a century later, Congress formally apologized for it.

The Chinese Exclusion Act blocked Chinese workers from coming legally to the country, and blocked Chinese immigrants who were already living here from becoming US citizens. The Library of Congress calls it the “first significant restriction on free immigration in U.S. history.”

The law and other related measures were repealed in 1943. But its legacy is still being felt decades later.

Generations of families were separated and suffered under the restrictions, says Ted Gong, executive director of the 1882 Foundation, which aims to spread awareness of the act’s history and continuing significance.

“The Chinese Exclusion Act shaped the entire Chinese American society, even up into today,” Gong says.

And experts have argued the law’s impact lasted long beyond its time on the books.

“The justification for exclusion was that the Chinese were an ‘unassimilable’ race and therefore could never become Americans. … Its rationale – that Asians pose a racial danger to American society – has endured in our politics and culture to this day,” historian Mae Ngai said in a 2021 piece for The Atlantic.

Chinese immigrants faced exploitation and racism

Large numbers of Chinese immigrants first began arriving in the United States during the California Gold Rush, drawn by the same promise of opportunity that brought many US citizens West.

The mass migration of speculators drove California’s population to more than quadruple in size in about a decade’s time, growing to more than 370,000 people by 1860.

But the realities of the rush were bleaker than the fantasies that had inspired many to make the move.

“The Gold Rush is often celebrated for the individual daring, ingenuity, and male camaraderies of the 49ers, engaged in a bold experiment in democratic self-government,” Ngai writes. “Less well remembered, but no less true, is that it was also violent and racist.”

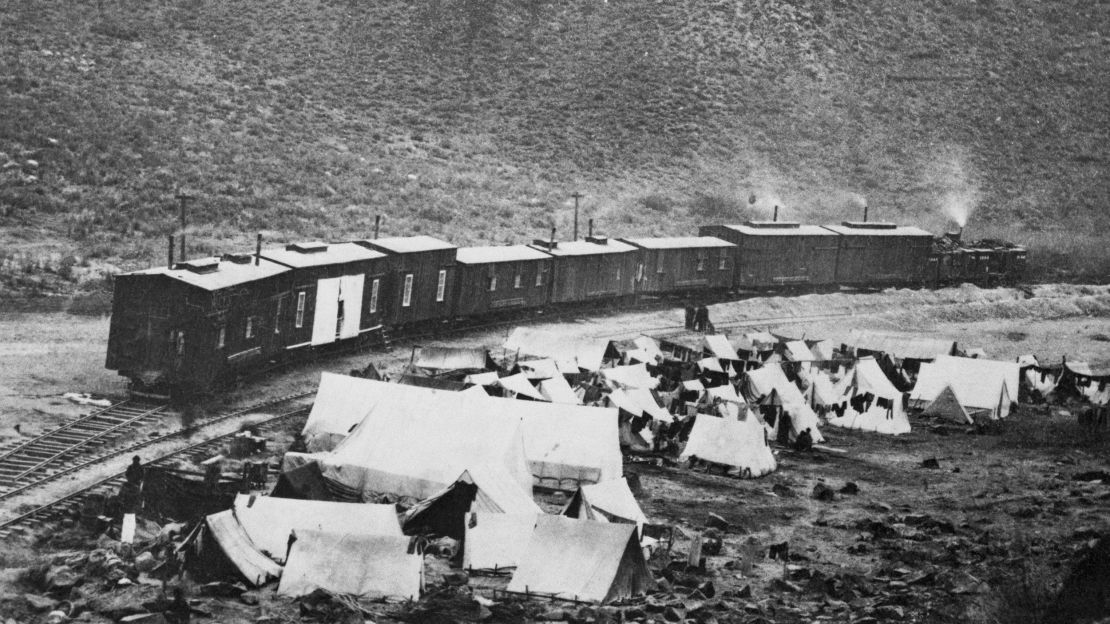

The racism and anti-immigrant sentiment many Chinese miners faced followed workers into other realms as well. Chinese workers played a vital role building the Transcontinental Railroad. They were often exploited and paid less for their labor, and infamously were left out of the 1869 photo celebrating the railroad’s completion, as historian Catherine Ceniza Choy notes in her book “Asian American Histories of the United States.”

What the Chinese Exclusion Act did

When economic panic swept the US in the 1870s, White citizens scapegoated Chinese immigrants for taking away jobs.

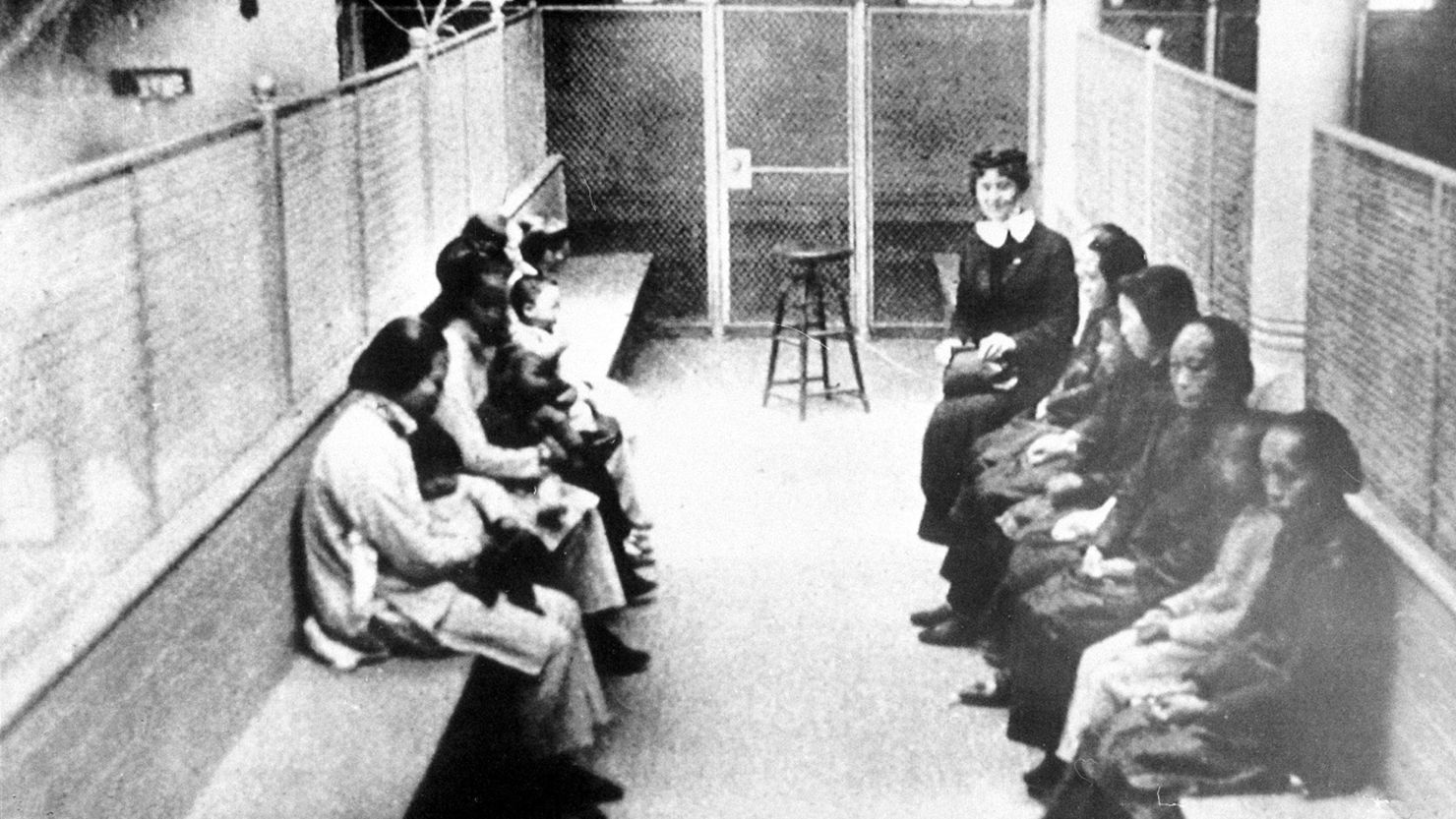

In 1875, the Page Act was enacted purportedly to restrict prostitution and forced labor. But in reality, it was used systematically to prevent Chinese women from immigrating to the US, under the pretense that they were prostitutes. And in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act blocked Chinese men from entering the country.

There were exemptions for merchants, clergy, diplomats, teachers and students, but the law blocked many people who previously could have immigrated to the United States, and many family members of immigrants already living in the United States.

Meanwhile, Chinese communities living in the United States faced increasing violence.

“In 1885 alone, the entire Chinese population of Tacoma, Washington, was violently expelled, and 128 Chinese coal miners from Rock Springs, Wyoming were massacred,” Ngai writes.

The hostile climate fueled a phenomenon that can still be seen in many US cities.

“That’s why Chinatowns were born,” Gong says, describing how many Chinese immigrants and their descendants were driven out of other locations and sought safety.

Other immigration restrictions followed

The Chinese Exclusion Act paved the way for further immigration restrictions.

“The Chinese-exclusion laws were subsequently extended to people from the Philippines, India, and Japan (indeed, an entire ‘barred Asiatic zone’ was established in 1917), lumping different national-origin groups into a single racial category, the ‘Asiatic,’” Ngai writes.

Canada published its own Chinese exclusion law in 1923.

And in the United States, additional measures were passed to crack down on Chinese immigrants.

Numerous states passed so-called Alien Land Laws between the 1880s and 1920s to bar Asian people from owning land.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first and only federal law to prevent a specific nationality of people from becoming US citizens.

It was extended for decades and remained in place until 1943, when it was repealed during World War II, as a State Department history notes, “in the interests of aiding the morale of a wartime ally.”

“You can’t fight a war against fascism and then say one of your primary partners is excluded from coming to the United States,” Gong says.

Lawmakers apologized decades after the law’s repeal

It took more than a half century for US lawmakers to apologize for the Chinese Exclusion Act and related measures.

On June 18, 2012, after House lawmakers passed a resolution expressing regret for the law, Rep. Judy Chu, D-California, called the Chinese Exclusion Act “one of the most discriminatory acts in American history.”

“It is for my grandfather and for all Chinese Americans that we must pass this resolution, for those who were told for six decades by the U.S. Government that the land of the free wasn’t open to them,” said Chu, who sponsored the resolution.

“We must finally and formally acknowledge these ugly laws that were incompatible with America’s founding principles.”

Some see echoes of the discriminatory law in today’s policies

The Chinese Exclusion Act may be a relic of the past, but its legacy is still echoing today.

Earlier this year, Madeline Hsu, a history professor at the University of Texas at Austin, told CNN she sees parallels between efforts to bar Chinese citizens and others from owning property in Texas and the Alien Land Laws that passed shortly after the Chinese Exclusion Act.

“It’s definitely sort of (a) reinvocation of kind of what people in Asian American studies would refer to as ‘Yellow Peril’ fearmongering,” she said.

And this year, which also marks the 80th anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act’s repeal, advocates who pushed for the congressional apology 11 years ago are hoping another branch of government will take up the issue: the president.

“This would be a good year to make that announcement from the White House, that statement of apology,” Gong says.

The goal, he says, is not to dredge up an issue from the past, but to stress America’s values going forward.

“We need to acknowledge the harm that was done. … We need to reaffirm what is right,” he says.

CNN’s Harmeet Kaur, Zachary Byron Wolf and Natasha Chen contributed to this report.