Editor’s Note: Victoria Nourse, a professor at Georgetown Law Center, formerly served as chief counsel to then-Vice President Joe Biden, as an appellate lawyer in the Justice Department and as special counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee. The views expressed in this commentary are her own. View more opinion on CNN.

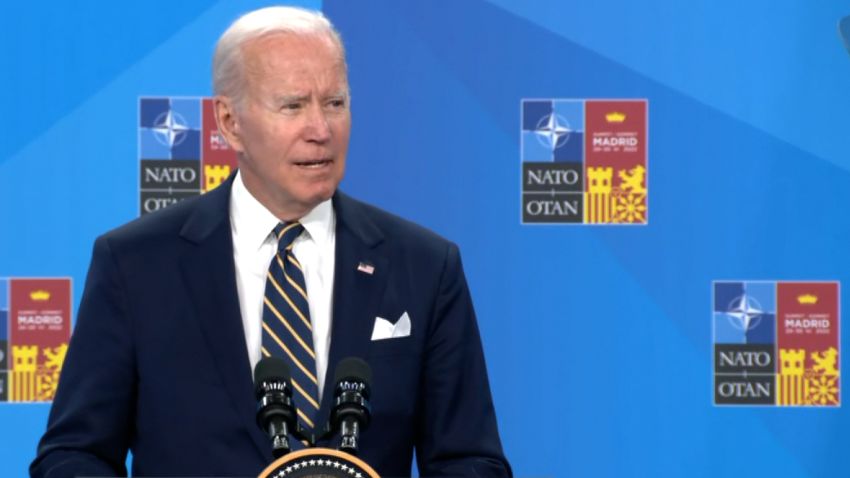

President Joe Biden, and many others, have rightly called for Congress to codify Roe v. Wade, establishing in law a national right to choose abortion. He said Thursday that he would even favor lifting the filibuster “to codify Roe v. Wade in the law.”

After all, the Supreme Court explained its Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health decision as returning the abortion question to the people and their elected representatives.

Right now, there are too few Senate votes to pass such a law. But that could change if the Democrats maintain all their seats in the Senate and flip one or two seats with senators who favor abolishing the filibuster. Of course, the politics might go the other way: if Republicans take the House and Senate, one can expect some of them to push for a national ban on abortion.

Constitutionally, however, there is a problem with thinking that federal legislation will resolve this issue and keep abortion from returning to the Supreme Court. Even if Congress passes a law codifying Roe v. Wade, that does not mean that the brazen precedent-busting Dobbs Supreme Court will not have five votes to strike down the new law.

That is the problem with those who say that the court is simply returning this issue to the people. If Congress tries to pass a law, either way, that law will likely land right back in the justices’ lap. The Supreme Court retains the power to reverse the people’s will as expressed in the actions of Congress. That is what the power of judicial review means. To quote the most famous case in constitutional law, Marbury v. Madison, it is for the courts to “say what the law is.”

Drafters of any federal Roe protection must not be starry-eyed. First off, people should stop using the term “codifying Roe.” The phrase is misleading. Codifying in this case means to enact a statutory right, which is possible, but the term “Roe” refers to a Supreme Court ruling and Congress has no power to reverse a particular Supreme Court ruling and reinstate a precedent that has been overturned.

In 2000, when Congress tried to overrule Miranda v. Arizona, for example, the court said “no” in a case called Dickerson v. United States: “Congress may not legislatively supersede our decisions interpreting and applying the Constitution.” Three years earlier, they said the same thing in City of Boerne v. Flores: “Congress does not enforce a right by changing what the right is… [Congress] has no power to determine what constitutes a constitutional violation.” In short, the moment a Roe codification is signed by the President, it will be challenged as unconstitutional, and we could be right back where we started – in the Supreme Court.

The current codification bill, the Women’s Health Protection Act, rests in part on the theory that Congress has power over “commerce,” and abortions involve commerce. But there are weaknesses in this argument. First, the court, not Congress, ultimately determines what is commerce.

Even when Congress has created an incredibly strong factual record showing a commercial connection, the court has sometimes seen fit to reject it. In the 2000 case, United States v. Morrison, the Supreme Court said that a sexual assault was not commerce, and therefore any national economic law allowing survivors to sue their attackers was unconstitutional – despite a “mountain of data” showing a link between women’s economic prospects and gender-based violence.

Second, if abortion is a crime as its opponents argue, then Morrison’s reasoning applies, barring congressional action. Morrison changed the court’s old liberal commerce analysis – where Congress could legislate on anything even vaguely connected to commerce – and barred Congress from addressing local, non-economic activity. A court bent on striking down Congress’s ability to restore Roe could describe abortion in non-economic terms, as an assault on fetal life, just as the court in Morrison described gender-based attacks as crime. At that point, no downstream “effect” on women or national commerce would matter to the constitutional question.

Third, now that Dobbs has given “fetal life” a constitutional interest, it is possible that a law extinguishing that constitutional interest could be considered fatally inconsistent with Dobbs itself.

To be sure, there are counterarguments and counter-precedents, showing that Congress has broad power to regulate markets and health care, but the very same court that wants to send abortion to the states, is also the court that has, since the mid-1990s, been cutting back on women’s rights and Congress’ power to protect women – even questioning the constitutional basis for Congress to pass the Affordable Care Act, former President Barack Obama’s health insurance program.

One might think that the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause should come to the rescue. The late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg famously said that the abortion question was one of equality, not the right to privacy.

Over the past 20 years, however, the Supreme Court has created a set of rules that limit Congress’ power to provide remedies for Fourteenth Amendment violations. Any law that Congress passes must be “congruent and proportional” to the constitutional violation.

Worse, Dobbs says that women have no equality interest in a procedure that can only be applied to women, reviving a much-criticized refusal of the Supreme Court in Geduldig v. Aiello to deem pregnancy discrimination unconstitutional.

Sad, but true: The Constitution provides no right against a company firing you because you are pregnant; that right only exists because of Congress, and only because the right was focused on commerce. Who knew that commodities would have more federal equal protection than women, but that is essentially what Dobbs holds.

Some might say this is fine: If Congress cannot codify Roe, it cannot impose a national abortion ban. But that does not follow from existing Supreme Court precedents. It is possible, depending upon how the laws are drafted, for the court to strike down a Roe codification and uphold a national abortion ban. How?

The Supreme Court could strike down a Roe codification because the court gets to decide constitutional questions. Meanwhile, if the national ban is written in the right way, it could survive that attack and find an easy home within the commerce clause. Such a ban would focus on commercial transactions – barring payment for abortion or uncompensated abortion services. The law would be more narrowly focused on commerce than the current Roe codification bill.

Is there an answer to this for Roe codification advocates? Yes. Very, very careful drafting, a raft of Senate and House hearings and clear thinking about the opposition. The bill must not say that it is changing constitutional law, it cannot rely upon the term “right to abortion,” for after Dobbs, there is none.

The drafters must focus on language that has already been upheld under the commerce clause involving the regulation of medical procedures. They should include language that specifically rejects, as a factual matter, the narrow Morrison analysis: “Congress finds that abortion is an economic activity and cannot be reduced to an operation or assault.”

Hearings must be conducted to show a factual basis for the link between commerce and abortion.

Members should emphasize why women’s actual life has constitutional protection that transcends the constitutional protection of potential life. They should rebut the Dobbs’ analysis of the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause, making clear that women are equal “citizens” under the “citizenship” clause of that amendment and that denying women the power to make medical decisions violates that amendment.

They should write language in the bill that would invoke the “privileges and immunities” clause of the Fourteenth Amendment as well as the Ninth Amendment, which the Dobbs majority did not address, since these texts could support an abortion right. They should rebut various originalist arguments made in the opinion that are based on shaky history.

The bottom line: the court is very definitely not “out” of the abortion business. It has just begun.