Editor’s Note: Peniel E. Joseph is the Barbara Jordan Chair in ethics and political values and the founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is also a professor of history. He is the author of “Stokely: A Life” and “The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.” The views expressed here are his own. View more opinion articles on CNN.

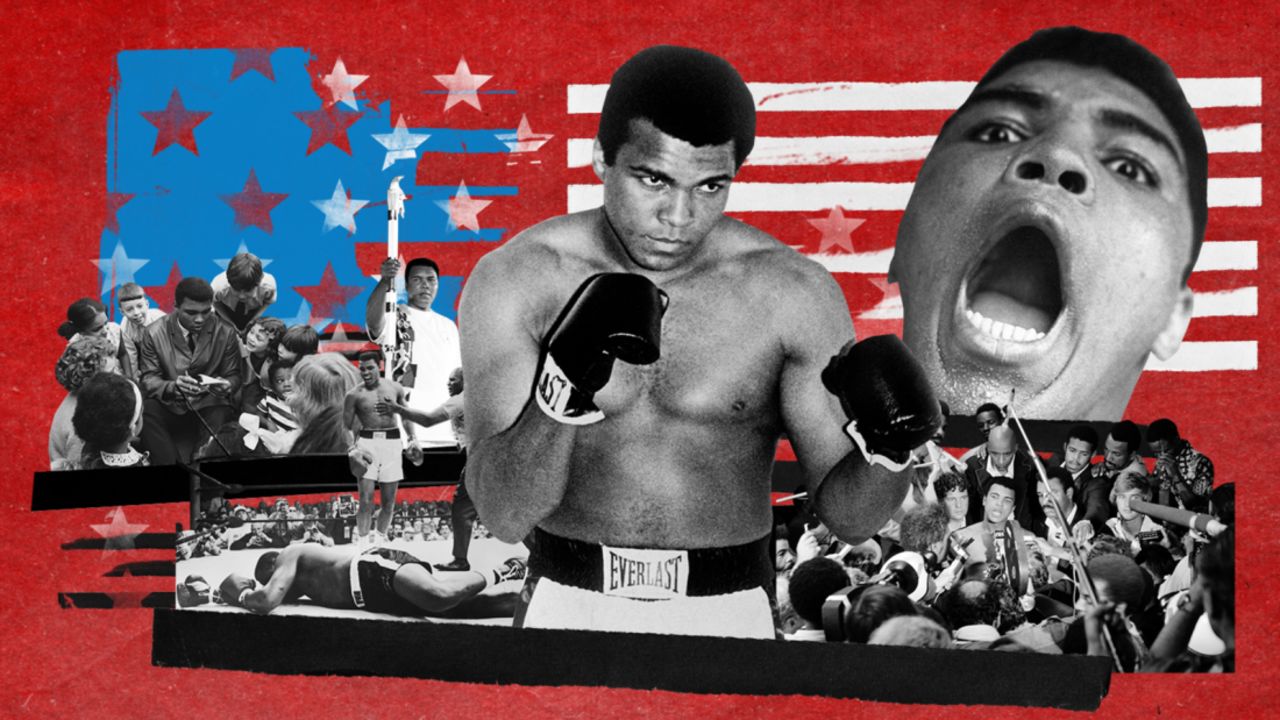

When Muhammad Ali died in 2016, he was accorded the equivalent of a state funeral, complete with a eulogy that featured President Barack Obama and former President Bill Clinton. During the last three decades of his life, from lighting the Olympic torch in Atlanta in 1996 until his death, Ali became a virtually sanctified figure, embodying the movements for civil and human rights that he came to symbolize in America and around the world.

As “Muhammad Ali,” a new four-part documentary series made by Ken Burns, Sarah Burns and David McMahon explains, it didn’t start out this way. The film’s cumulative power, for both a historian familiar with the period and for people less familiar with this history, is its ability to unpeel hidden layers of a story that has become American folklore.

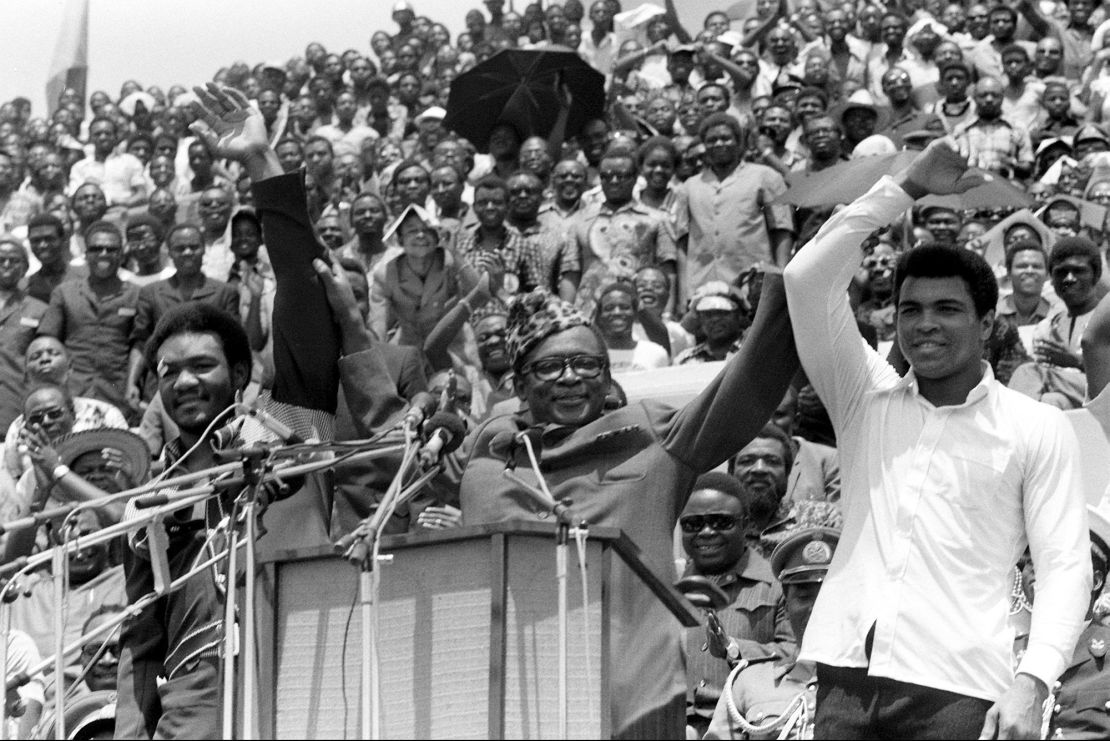

“Muhammad Ali” offers the most fulsome portrait of the iconic sports star to date, showing him to be a man full of paradoxes. A freedom fighter who abandoned one of his early mentors, Malcolm X, in favor of a group that would take advantage of him for over a decade. A Black nationalist and pan-Africanist who warmly shared the stage with the dictator Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire, whose legendary corruption and record of human rights violations seemed antithetical to Ali’s human rights advocacy. A family man whose multiple marriages were marked by infidelity.

The film successfully illuminates how the highs and lows of Muhammad Ali’s life personify much of the political conflict and racial upheaval that marked American life – and the larger world – in the 1960s. The mythology of Ali that emerged in the 1990s onward tends to sanitize this legacy, making the icon a more comfortable exemplar of American exceptionalism by smoothing his rough edges (and America’s, too). This documentary’s greatness lies in how it reminds a new generation of audiences that Muhammad Ali’s athletic excellence and political rebellion mutually defined not only his time but also our own era of racial and political reckoning.

“Muhammad Ali” expertly locates the roots of the age of Black Lives Matter in the political storms of the 1960s. The film’s depictions of that era’s racial segregation, police brutality and cultural antipathy for Black folk feel achingly familiar to contemporary audiences.

Ali’s audacity – telling reporters (and many White Americans) in 1964 after becoming world heavyweight champion, “I don’t have to be what you want me to be, I’m free to be who I want” – disrupted an unspoken racial compact for Black athletes and reimagined the boundaries of the possible in ways that anticipated our present moment.

Born and raised in the violently segregated city of Louisville, Kentucky, of the 1940s and 1950s, Cassius Marcellus Clay came of age in a historical milieu indelibly shaped by race. Clay was only six months younger than Emmett Till, whose 1955 lynching in Mississippi sent shockwaves throughout the nation, including Clay’s hometown.

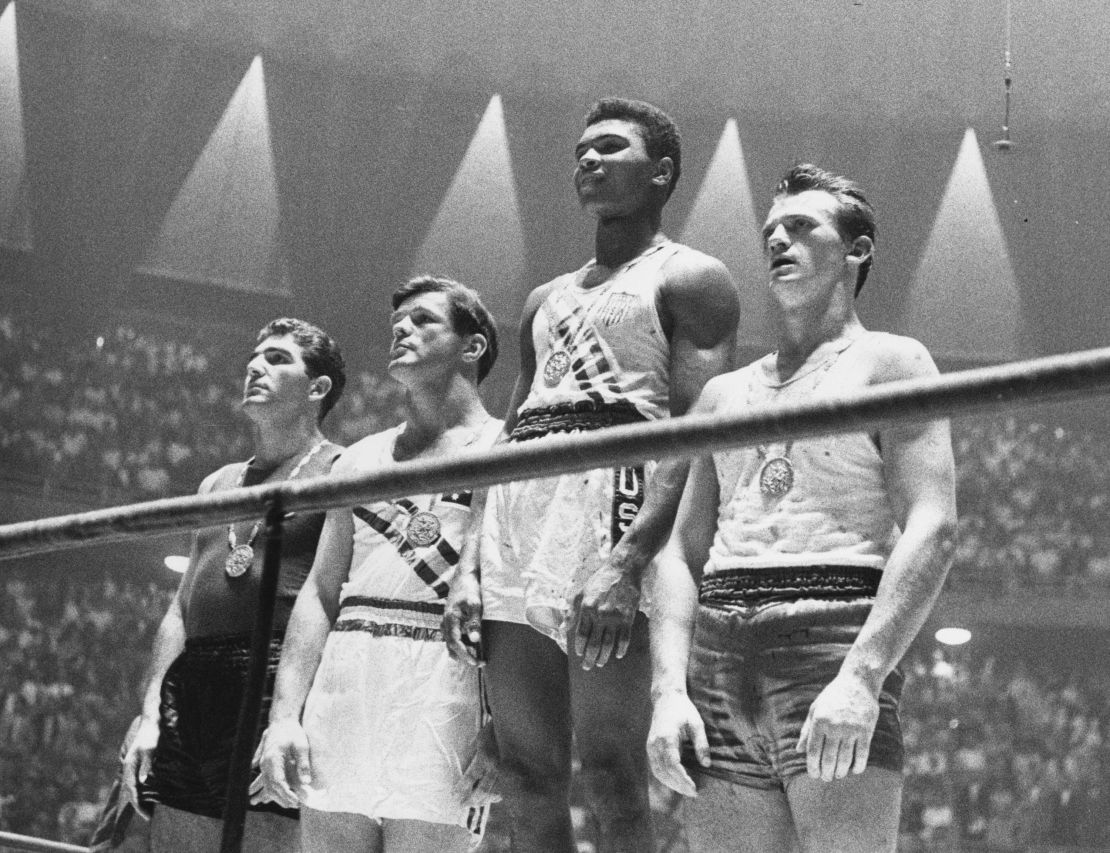

The young Clay found a safe haven in boxing, where he displayed keen observational abilities to go along with the fastest hands in the history of heavyweight boxing; by 1960, at the age of 18, he had won an Olympic gold medal in Rome. At first, reporters loved the handsome, brash and cocky young fighter whose quotable lines – like “I’m so mean, I make medicine sick” – made for good copy.

Until they didn’t.

One of the many pleasures of Ali documentary is watching Clay’s evolution into Muhammad Ali. Clay had purposefully stayed out of the civil rights struggles that were increasingly making headlines during the early 1960s – better to protect his sponsors, “the Louisville Syndicate,” the White power brokers bankrolling his early career. Yet he yearned for a personal dignity that he quickly realized could not be bought.

Clay found inspiration in the Nation of Islam; an encounter with a Nation of Islam member selling the newspaper, “Muhammad Speaks,” in Miami, where he trained for fights, piqued his curiosity about becoming a Muslim. Attending religious services at Miami’s Temple No. 29 Mosque, where ministers preached that God was Black, showed Clay an alternate reality to the institutions of White supremacy normalized in his youth. Clay flourished, hearing a message of Black political and cultural self-determination that dovetailed with his own aspirations for enjoying a kind of personal dignity perpetually denied to African Americans.

The film provides a potent explanation to why Clay became so attracted to the Nation of Islam. Rather than abandon the Black world he grew up in for anticipated riches, Clay sought dignity for himself and others. As a budding NOI devotee, Clay met Malcolm X, the group’s national representative, who would become one his most important friends and mentors. Clay and Malcolm grew attracted to each other’s hidden depths, rarely visible to the general public.

“Muhammad Ali” slows down the story of the young champion boxer’s rise enough for us to see the risks – some would say reckless – the young Clay took in shaping his personal and professional destiny. Drawn to a religious group characterized by some mainstream journalists as “Black supremacists” held the potential to destroy Clay’s boxing career, but he refused to back down, maintaining his religious faith as a protective shield against racist insults and threats.

The film also explores Ali’s eventual rejection of Malcolm X in detail, offering one example of the way in which the champ’s charisma and bravado at times concealed a gift for self-preservation that could be ruthless.

While guiding Ali’s evolution in his identity as a Black Muslim, Malcolm X was falling out with the leader of the National of Islam, Elijah Muhammad. Malcolm broke with Muhammad in early 1964, announcing his plans to form his own organization. In May 1964 Ali toured Africa on a trip initially orchestrated by Malcolm, with whom he briefly reunited with in Accra, Ghana. Malcolm tried to greet him; with harsh words, Ali turned away. Their friendship ended there, to Ali’s later regret, especially since Malcolm was killed the following year in a political assassination while giving a speech in New York.

As the film shows, Ali became, by his trip to Africa, a global symbol of Black pride. He embraced the NOI’s racial separatism not out of weakness but from a position of strength. He basked in his growing celebrity, meeting with African leaders, wading through tremendous crowds and deepening his ties to a global Islamic community.

Ali’s personal belief in Islam dovetailed with political convictions about the need to confront White supremacy, no matter the cost. “Muhammad Ali” illustrates how even as his significance to Black communities in the United States and abroad grew, Ali’s charisma, bravado and humor curdled in the eyes of millions of White Americans as he strayed further from their idea of what a Black male athlete should be. Ali’s refusal to fight in, or approve of, the Vietnam War turned him into a despised figure in mainstream America and burnished his stature as a countercultural icon.

Denied status as a conscientious objector, hounded by a boxing commission’s refusal to let him fight domestically, Ali fought overseas throughout 1966 before being stripped of his boxing license and heavyweight championship the next year, for refusing to be drafted into the army.

Sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine for resisting the draft in 1967, Ali became an itinerant Black Power spokesperson, with the NOI distancing themselves from the former champ as he faced stiff political headwinds. In so doing, Ali became a model for Black resistance to systemic racism domestically and American imperialism abroad.

The fighter once so quick he could evade the blows of all of his opponents now discovered that he could take a punch, figuratively and literally. In the 1970s Ali engaged in a series of brutal matches, fighting Joe Frazier three times, and regaining the heavyweight championship in an upset victory over George Foreman in the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Kinshasa, Zaire (now Democratic Republic of the Congo).

Ali’s professional redemption paralleled the rise of anti-Vietnam War sentiment in America. His popularity within the Black community spread into the mainstream and he became a kind of Rorschach test for the nation. His professional rivalry with Joe Frazier re-captivated the imagination of the predominantly White sports world. The film documents how Ali vilified Frazier as “ugly” and “dumb,” a man whose only admirer was conservative President Richard Nixon. In these and other instances the viewer gets detailed portraits of Ali’s cruelty, casual at times, in service of his own ambition.

In defeat Ali became a figure who earned admiration and empathy. Losing to Frazier, as he did in front of millions on television and multiple celebrities in “The Fight of the Century” in 1971, humanized him in the eyes of White Americans and amplified the love Black folks held for him. He made disastrous financial decisions, supporting a gigantic entourage, giving money away to strangers and allowing the Nation of Islam to control his finances, as detailed in journalist Jonathan Eig’s superb recent biography, “Ali: A Life.” The film also documents Ali’s insatiable womanizing and the emotional trauma this inflicted on his wives and family

Part of the heartbreak of Ali’s story is his seemingly endless appetite for punishment and suffering. A promise to retire following his 1975 “Thrilla in Manila” – his final battle against Joe Frazier – faded until his last fight in 1981, a sad beating at the hands of the unremarkable Trevor Berbick, which ended his boxing career for good. He emerged from his boxing career with a slower gait, halting speech and the symptoms of the Parkinson’s diagnosis that would come in the 1980s.

Get our free weekly newsletter

“Muhammad Ali” restores so many of the beautiful and ugly parts of Ali’s global legacy. For many Americans who came of age after Ali’s boxing career was long over, the image they know of the icon is of a trembling man, lighting the Olympic torch in Atlanta in 1996. Now this film brings to life for those viewers the Ali who in his prime rejected an American Dream rooted in racial animus against Black people, who proudly adopted a Muslim name and projected an unapologetic pro-Blackness. His principled anti-war stance fulfilled Malcolm X’s prediction that the young boxing champion from Louisville would become a symbol for millions of the world’s dispossessed. Ali became an avatar of social and political change, not when he made it look easy in the ring, but when things got harder.

Ali’s personal and political odyssey was an American epic, one that “Muhammad Ali” allows us all to experience.