Editor’s Note: Sonja West is the Brumby Distinguished Professor of First Amendment Law at the University of Georgia School of Law. The views expressed in this commentary are her own. This is the next installment in CNN Opinion’s series on the challenges facing the media as it is under attack from critics, governments and changing technology.

Story highlights

Sonja West: Near v. Minnesota and the Pentagon Papers are two seminal free-press cases

Both ensure that journalists can publish classified information, writes West

President Donald Trump has made it clear that when it comes to cracking down on government leaks to the media, “the tougher the better!” Yet for all of Trump’s dire warnings about the dangers of leaks, there is one action that even he has not suggested – a court order blocking the press from publishing leaked information.

Why would a president who calls journalists “the enemy of the American people” even hesitate to use the force of the law to stop the press from revealing classified information? Because the United States Supreme Court has told us that prior restraints (as such pre-publication orders are legally known) are presumptively unconstitutional.

This now-established vital press protection, however, was not always a given. In fact, it almost wasn’t found to be a right at all. But in two landmark cases the Supreme Court cemented this freedom as a crucial safeguard in protecting America’s free and independent press.

The Near case

The issue first came to the Court in 1931 in a case called Near v. Minnesota, which involved an unsympathetic and unlikely champion of the First Amendment – Jay M. Near. Near was the bigoted and unscrupulous publisher of The Saturday Press, a Minneapolis scandal sheet that specialized in spreading generally true but frequently reckless accusations of local corruption. Each issue during the paper’s short run featured hate-filled diatribes alleging that Jewish mobsters, in collusion with local officials and law enforcement, were running illegal gambling, bootlegging and racketeering operations throughout the city.

Angered by Near’s often-personal attacks, local officials turned to a little-known state law that empowered a judge to shut down any newspaper he deemed to be “malicious, scandalous and defamatory.” Under the law, The Saturday Press was permanently banned from all future publication, and Near faced up to a year in jail if he violated the order.

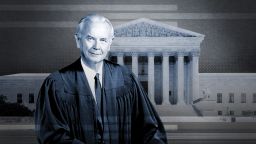

A challenge to the law ended up before the United States Supreme Court. The justices on the Court at the time were unlikely to side with a shady muckraker like Near, but the sudden deaths of two of the Court’s conservative members created fresh uncertainty. And to the surprise of many, it was ultimately the newly appointed Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes who announced the Court’s 5-to-4 ruling that the state law was unconstitutional. Near had won his case by a single vote.

Prior restraints are the “essence of censorship” and violate the “chief purpose” of the First Amendment, Chief Justice Hughes wrote for the Court. The media could, of course, still be punished after publication if they were guilty of defamation or another offense, but the government could not preemptively stop the press from publishing.

The Near Court, however, did not declare that the government could never impose a prior restraint on the press. There were possible scenarios, particularly those involving national security, in which such an order might be upheld. “No one would question,” Chief Justice Hughes wrote, “but that a government might prevent … the publication of the sailing dates of transports or the number and location of troops.”

The Pentagon Papers

The ruling in the Near case was largely left unchallenged for 40 years. But in 1971 it was put to the test in a high-profile case pitting the most powerful newspaper in the country against a president who was determined to silence it.

Earlier that year, the New York Times had received a 7,000-page classified report (known as the Pentagon Papers), which detailed the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War. After carefully analyzing the information, the paper began publishing a seven-article series about the secret documents. President Richard Nixon responded quickly, and within two days the administration had won a federal court injunction ordering the paper to stop the series.

What followed was unprecedented in this country before and since. For two weeks the largest newspaper in the country was prohibited from publishing truthful, newsworthy information.

The case raced to the Supreme Court, where the justices were faced with a crucial question: Was this the moment that Chief Justice Hughes had warned about in Near? Was the information in the Pentagon Papers a threat to national security akin to the publication of the location of troops?

Moving with uncharacteristic speed, the Court said no. By a vote of 6-to-3, the justices held that the government had not met the “heavy burden” established in Near to warrant a prior restraint. In the words of Justice William Brennan in his concurrence, the government failed to show that publishing the information would “surely result in direct, immediate, and irreparable damage to our Nation or its people.”

Justice Hugo Black also wrote separately in support of the decision, stating that the framers of the Constitution intended to protect the media from government censorship so that they could check the government and inform the public. “In revealing the workings of government that led to the Vietnam War,” he wrote, “the newspapers nobly did precisely that which the Founders hoped and trusted they would do.”

Their impact today

The Near and Pentagon Papers cases solidified the United States’ uniquely strong constitutional tradition against prior restraints of the press. Thanks to these cases, any president who tries to censor the press prior to publication will face a formidable First Amendment hurdle.

Get our free weekly newsletter

And that includes President Trump. Though he hasn’t taken steps to legally silence the press, he has repeatedly criticized the media for publishing leaked information. “Leaking, and even illegal classified leaking, has been a big problem in Washington for years,” he declared on one occasion, “Failing @nytimes (and others) must apologize!”

First Amendment attorney Floyd Abrams, who represented the New York Times in the Pentagon Papers case, told me that the protections this case provided might be especially important during the Trump administration.

“We cannot predict today which publication will so inflame the president that he would seek to block publication of news, if he could,” Abrams said. “But we can expect that that day will occur. When it does, the Pentagon Papers case will stand as a powerful barrier against any effort to suppress publication.”