Editor’s Note: Karl Kusserow is the John Wilmerding Curator of American Art at the Princeton University Art Museum. He is the author and editor of five books, including the forthcoming “Picture Ecology: Art and Ecocriticism in Planetary Perspective” (2021). The views expressed here are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

Last month, the House Judiciary Committee recommended the creation of a “commission to study and consider a national apology and proposal for reparations for the institution of slavery.”

First proposed in 1989 by Michigan Democrat John Conyers, House Resolution 40 was reintroduced annually up to his retirement in 2017, only to be voted down. Recently championed by another Black legislator, Sheila Jackson Lee, Democrat of Texas, the bill still faces uncertain prospects, though it has in President Joe Biden, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi the support of three of the nation’s most powerful politicians.

Thirty-two years is an uncommonly long time for a bill to languish in committee, but April 14, the day on which this one was finally approved, offers some additional historical perspective: it was the 156th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. The legacy of slavery goes deep in this country. Looking closely at an iconic history painting and a contemporary reinterpretation of it helps us recognize racism’s abiding shadow and envision a more just future.

Despite its prosaic official title – the Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act – the resolution reveals a bit of poetry in the shorthand by which it has subsequently been known. The “40” in HR 40 refers to the “forty acres and a mule” that Union General William Tecumseh Sherman included as part of Special Field Orders No. 15 in 1865, near the end of the Civil War.

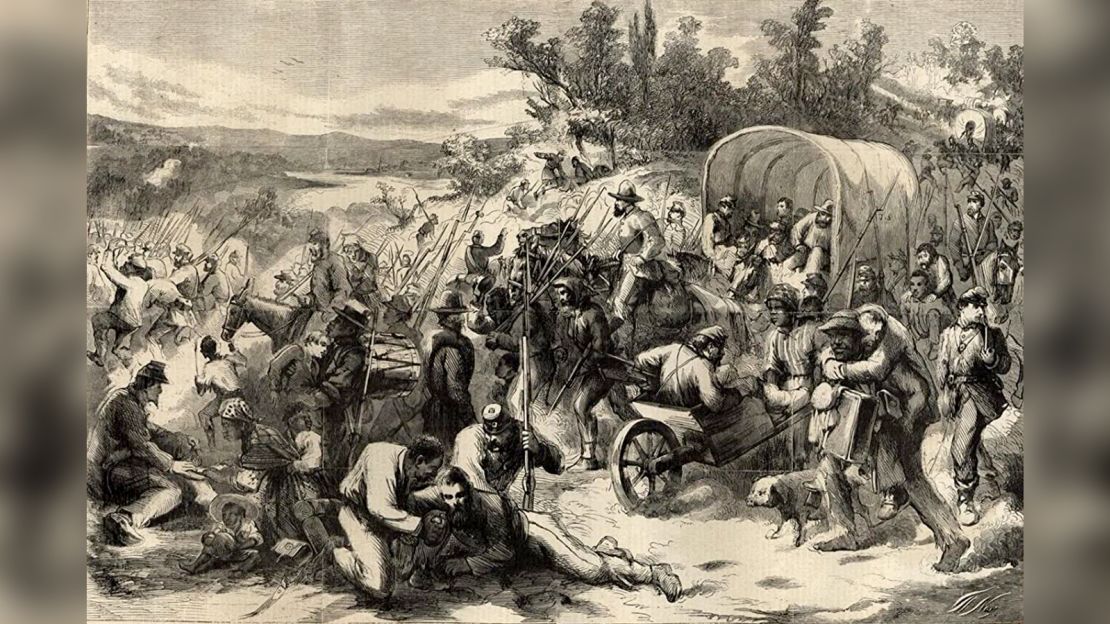

Over the course of his “March to the Sea” from Atlanta to Savannah, more than 10,000 Black refugees had joined the Union troops, becoming “contrabands” – captured enemy property – in the callous terminology of the day. Famed illustrator Thomas Nast depicted some of them in a Harper’s Weekly wood engraving, feeding, nursing and even carrying the wounded and bedraggled soldiers on their backs.

Faced with how to accommodate these unofficial volunteers at the conclusion of the military campaign, Sherman appropriated 400,000 acres of coastal land, providing for its division and distribution to the formerly enslaved African Americans – a kind of initial attempt at reparations.

Notwithstanding the boldness and scope of Sherman’s directive (which was quickly annulled by President Andrew Johnson), it assisted only a small fraction of enslaved Americans. The last census completed before the war, in 1860, matter-of-factly reported that among the nation’s 31,443,321 inhabitants, “3,950,000 are slaves,” an astonishing 13% of the population.

That proportion remains uncannily relevant today, equating roughly to the current percentage of African Americans in the US population. In the argument for reparations, one need look no further than the substantially greater percentages of Black people in the US living in poverty, who are incarcerated, have perished from Covid-19 and are killed by police – among many other bleak metrics – to grasp the moral imperative for redress.

Whatever its ultimate fate, HR 40 will now move forward for floor debate in the House of Representatives. Outside that grand chamber, an equally grand painting – measuring 20 by 30 feet – by American artist Howard Chandler Christy is permanently installed. Completed in 1940, “Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States” shows the particular moment on September 17, 1787, when a North Carolina delegate to the Constitutional Convention, Richard Dobbs Spaight, added his name to the document.

It appears that some sort of vote or roll is also going on in Christy’s painting. The figure at the center of the composition, with four fingers raised as if in counting, is William Jackson, the convention’s secretary, who casts his eyes toward the trio of figures at left with upraised arms – Charles Pinckney, his relative Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Pierce Butler.

They were, like Spaight, Southern planters who supported slavery, and were among those on whose account the infamous Three-fifths Compromise, stipulating that enslaved persons would be counted for purposes of determining proportional representation as three-fifths of a person, was made.

Charles Pinckney had presented the three-fifths plan earlier in the convention, and further insisted his state of South Carolina would reject the Constitution if it prohibited the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Yet the figure around whom the canvas truly seems to revolve is neither Pinckney nor George Washington, standing on the dais at right, but Benjamin Franklin, seated in blue at its very center. If we can discern in the painting a subtext about the debate over slavery, this would be appropriate, since Franklin’s own views on the subject evolved from early, conflicted accommodation (he had once been a slave owner) to later abolitionism. His last public act was to send Congress a petition entreating it to “promote mercy and justice toward this distressed Race.”

Christy’s painting, then, though ostensibly celebratory, also depicts the elemental schism and atrocity at the root of American history.

By contrast, a recent appropriation of and variation on Christy’s work by Jamaican American artist Renee Cox communicates no such ambivalence. Her huge photograph, “The Signing,” created in 2018 and printed in sizes up to 15 feet wide, re-imagines Christy’s cast of bewigged White men as full of color and diversity of gender and costume. Cox “flips the script,” as she said the day after the bill left committee, to “give people who were considered three-fifths of a person when they wrote the Constitution a presence” by creating “images of themselves that are uplifting, empowering, and joyful.”

In Cox’s photo, the artist herself stands in for Washington – a Black woman claiming the same stage as the White founding father who once owned people of color. Benjamin Franklin is replaced by a turbaned, caftan-attired figure similarly resplendent in blue. And behind him, the man who supplants secretary Jackson in Christy’s painting holds his fingers down, his fist closed as if to disavow the legitimacy of the enterprise represented in that image, while also evoking the pride and solidarity of the Black Power salute.

Imagine placing Cox’s visionary photograph alongside Christy’s historic canvas in the halls of the Capitol, still so recently the site of a racially motivated riot. Similar in composition, but radically, poignantly dissimilar in content, the juxtaposed works could encapsulate the abiding national contests between myth and reality, White and Black, race and representation that lie at the heart of our past and present. Perhaps then, when HR 40 at last arrives on the House floor, those debating the bill might similarly think anew about what it means.