Editor’s Note: This story has been updated from its original version. Kate Andersen Brower is the author of “The Residence,” “First Women,” “Team Of Five” and “First In Line.” She covered the Obama administration for Bloomberg News, is a CNN contributor and is a consultant on the CNN Original Series “First Ladies,” airing Sundays at 10 p.m. ET/PT. The views expressed here are her own. View more opinion on CNN.

In many ways, having Jill Biden as the next first lady of the United States wouldn’t be revolutionary. The 69-year-old educator would be similar to most of the presidential spouses before her: She’s a straight, White woman who’s been around politics for decades, and holds some influence over her partner’s decisions (see: Kamala Harris).

But as Joe Biden wins the election to become the nation’s 46th president, Jill Biden as FLOTUS would be different in one very simple and very fundamental way: She would keep her day job.

Biden has said that no matter the election outcome she plans to continue teaching at Northern Virginia Community College, just as she did during the eight years she served as second lady. That means Biden, an English professor with four degrees, is set to become the first professor FLOTUS.

To even consider this as notable shows how anachronistic the role of America’s “first lady” really is. But no woman in the position’s 231-year history has ever held a paying job while also living in the White House. In a C-SPAN interview, former first lady Laura Bush said that this is “the real question”: It’s not about whether first ladies should be paid – Bush thinks they shouldn’t – but whether they should be able to continue their professional careers.

“That’s what we’ll have to come to terms with,” Bush said. “Should she have a career during the years her husband is president in addition to serving as first lady?”

The Bidens have been married more than 40 years, and in that time Jill Biden has been a supportive spouse and a sounding board. This was her husband’s third time running for President, in addition to his 36 years in the Senate and eight years serving as Barack Obama’s VP. She has had arguably more time than any of her predecessors to imagine what she would do if she were to become the first lady.

With a position as nebulous as this one, now seems like the perfect time to reimagine it. The role of first lady is not enshrined in the Constitution, and there is absolutely no job description and no salary. Yet there are still time-consuming duties first ladies are expected to perform, like planning Christmas parties and the Easter Egg roll, and helping with seating charts and menu selection for formal dinners.

At a time when 29 percent of heterosexual women are their family’s breadwinners, this presumption that the first lady position will be filled by an unpaid wife seems a throwback – especially since these women help get their husbands elected before they’re confined to the East Wing.

A job with no description

Between 1993 and 2017, all of the first ladies had advanced degrees. Michelle Obama and Hillary Clinton are lawyers, and Laura Bush has a master’s in library science. But none of them maintained a career while in the White House. If Jill Biden continues to work, it will force us to have a national conversation we haven’t seriously had before: We’d need to reconsider the traditional limitations placed on the most visible married woman in the country.

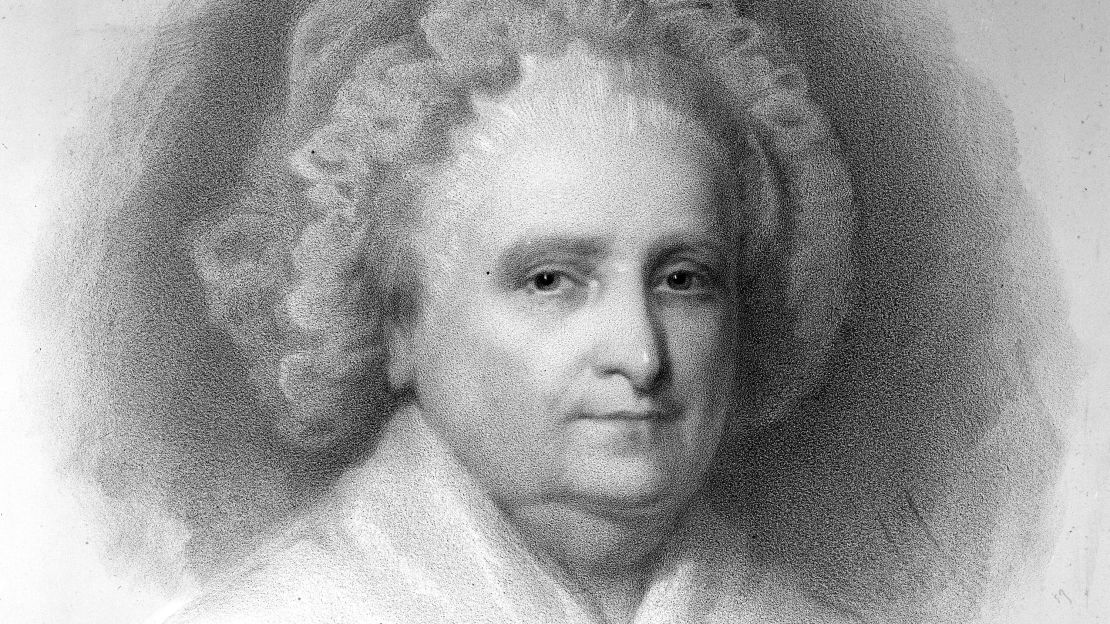

Beginning with Martha Washington, each first lady has had to interpret the expectations, opportunities and limitations of the job herself, capitalizing on her personal strengths to try to define the role.

For Washington, that meant being the presidential hostess, inviting dignitaries and members of Congress to the presidential mansion in Philadelphia because she thought it would help legitimize the new democracy.

That was also the beginning of validating the valuable role of a president’s spouse, although she wasn’t recognized as a “first lady” yet; instead, she was usually referred to as “Lady Washington” and sometimes “our Lady Presidentess.” It wasn’t until Harriet Lane, the niece of President James Buchanan, began accompanying the lifelong presidential bachelor to events that the unofficial title of “first lady” was used. (Harper’s Weekly referred to Lane as “Our Lady of the White House” in 1858, despite the fact that in the 19th century a woman’s name was to appear in writing on only three occasions: upon her birth, her marriage and her death.)

By the time Mary Todd Lincoln moved into the White House in 1861, the term “first lady” was ensconced in the American lexicon – showing how much quiet power multiple women had brought to the position over its first 72 years. And yet, the president’s spouse was still expected to only be a hostess, like Washington.

More than meets the eye

In reality, the most popular first ladies have done much more than serve as hostesses; they’ve humanized their husbands on the campaign trail and in office, operating more as diplomats than party planners.

It’s only because we know so little about them that these women often become caricatures, either trivialized or romanticized, and relegated to being adjacent to the political sphere rather than where they actually are: right in the thick of it. In her memoir, Michelle Obama called it a “strange kind of sidecar to the presidency.”

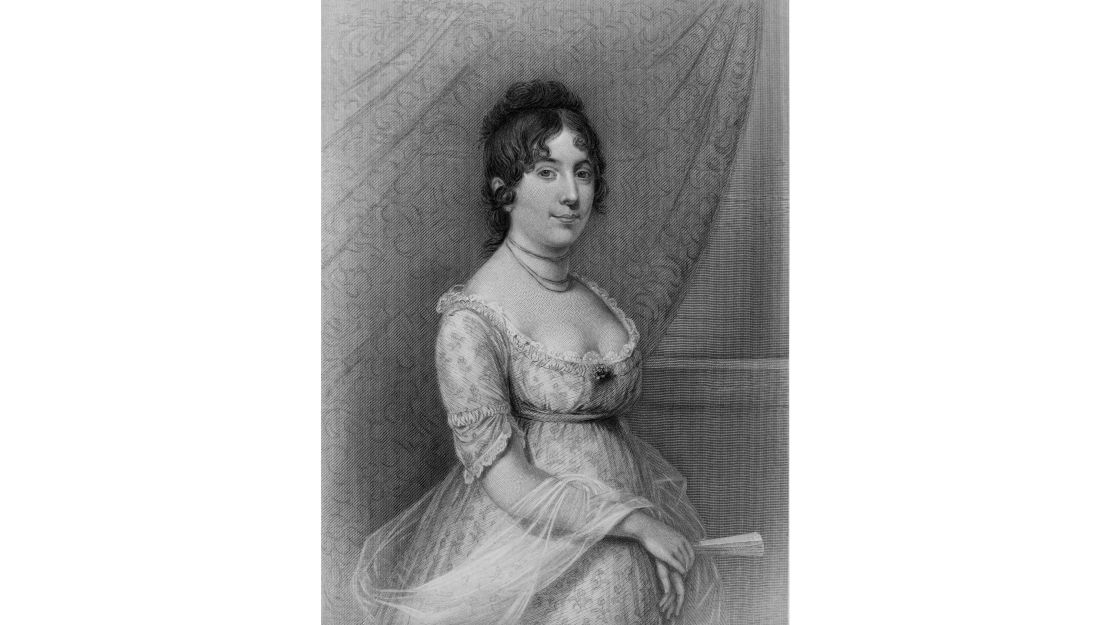

For instance, Dolley Madison, the wife of James Madison, is most famous for saving a portrait of George Washington as the British looted and burned the White House toward the end of the War of 1812. But Madison didn’t rescue the treasured portrait without help – Paul Jennings, an enslaved African American teen at the White House who was born into slavery at the Madisons’ Virginia estate Montpelier, helped save the full-length portrait before fleeing the fire. Madison knew the story captured the American imagination and would help secure her place in history.

“The tale, lauding the First Lady’s quick thinking in a moment of crisis, eventually found its way into American folklore through schoolbooks, monographs, and artwork,” according to the White House Historical Association. “She repeated the story frequently for the rest of her life, reminding listeners of her bravery and love of country.”

But concern for White House valuables was not Madison’s most lasting influence, and it was not something she accomplished alone; that would be her work as a political partner to her husband, using her natural talent as a hostess to forge bipartisan relationships.

Every first lady has been underestimated by the public, and even by their husband’s own advisers. Today, Eleanor Roosevelt is thought of as an activist first lady who was an outspoken advocate for women and African Americans. As the longest-serving first lady, she made the role extremely influential by holding weekly press conferences and writing a syndicated newspaper column. And she made a powerful point for racial justice when she resigned from the Daughters of the American Revolution after they refused to allow celebrated African American singer Marian Anderson to perform in Constitution Hall, which they owned.

But long before Roosevelt was appointed to the position of U.S. Representative to the General Assembly of the United Nations, she struggled to use her vast intellect for good. A member of FDR’s administration said she should stay out of her husband’s business and “stick to her knitting.”

Seen and not heard

Over the years, a first lady’s power has become too obvious to ignore. Nancy Reagan, the political consultant Stuart Spencer once said, was “the human resources department” for her husband’s administration. She helped decide who would be in her husband’s cabinet, and she famously helped get her husband’s chief of staff, Donald Regan, fired. And unlike some of her predecessors – including Jacqueline Kennedy, who said the title sounded “like a saddle horse” – Reagan proudly put “First Lady” as her occupation on her income tax form. She had worked hard for it.

When Hillary Clinton arrived at the White House, she tried to give the position the same professional stature she’d held as a lawyer: She moved the first lady’s office into the West Wing and played an active and unapologetic part in major policy decisions. She built on that experience to become the only first lady to run for office, serving as a senator and as secretary of state before running for president twice. We later learned that she even helped make Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who passed away on September 18, the second woman on the Supreme Court: “I may have expressed an opinion or two about the people he [Bill Clinton] should bring to the top of the list,” Clinton said at an event last year.

But her attempts to redefine the role for the public were largely unsuccessful. Bill Clinton’s decision to appoint her to lead health care reform days after taking office, for example, did not mesh with what most Americans wanted. A Gallup poll found that after the 1993 inauguration, Hillary Clinton was viewed favorably by 67 percent of Americans. By July 1994, only 48 percent rated her favorably, with a large number saying she had overstepped by having an office in the West Wing. Clinton even told her successor, Laura Bush, that if she could turn back time she would not have had an office in the West Wing – after health care reform failed she rarely used it anyway, she said. Clinton’s aides told Laura’s staff that once it had been done, undoing the controversial office arrangement would have raised too many questions.

Clinton’s experience taught future presidential spouses that a first lady can be as privately influential as she wants, but Americans do not want to see her revel in that influence. In many ways, we have not moved far beyond the criticism of Eleanor Roosevelt: Most people still believe that first ladies should be seen and not heard.

As the first African American first lady, Michelle Obama was a trailblazer. But it came at a high personal cost. She said that she knew from the very beginning of her eight years in the White House that she would be judged by “a different yardstick… . If there was a presumed grace assigned to my White predecessors, I knew it wasn’t likely to be the same for me.”

Obama more closely followed in the footsteps of Laura Bush than Hillary Clinton. A Princeton and Harvard Law School graduate who’d had a thriving career before her husband’s presidency, she chose to highlight her role as “mom-in-chief” upon entering the White House, and her devotion to the Obamas’ two daughters remained her top priority. That’s one of the reasons Obama was so relatable; she was frank about the realities of balancing parenthood – a job in itself – with the duties of her high-profile position. “When people ask me how I’m doing,” she explained, “I say, ‘I’m only as good as my most sad child.’” And in a country that has so often sought to disrespect and diminish Black women as mothers, seeing Obama claim the mantle of mom-in-chief was also a politically subversive gesture.

The challenge of a working FLOTUS

With her husband’s win, Biden will quickly be compared to predecessor Melania Trump, who, in many ways, has been a radical first lady from the start. She refused to immediately move into the White House, and she made her private lobbying public when she called for deputy national security adviser Mira Ricardel to be fired. Trump has been both a traditional first lady, focusing on her role as a mother, and a norm-breaking FLOTUS who seems to shrug at some of the institutional expectations. (According to a taped phone conversation with a former aide, she’s privately bristled at some of the conventional duties, like holiday decorating.)

Biden would more likely seek to blend the tenures of Clinton and Obama, who she worked closely with on issues having to do with supporting military families. And keeping her day job would be a challenge, both because she would have an incredible opportunity to make real change as first lady, and also because she would be much more recognizable than she’s ever been before.

She has long sought to distinguish herself from her husband’s career and carve out her own identity. She got her doctorate under her maiden name, Jacobs, instead of Biden. And later, when her husband was vice president and students signed up for her class, she was listed as simply “staff.” Her Secret Service detail dressed as students to blend in. That kind of anonymity would be impossible with the added title of FLOTUS.

But if history has taught us anything, it’s that Americans should never underestimate the first lady. They are often beloved and occasionally vilified, but they are almost always their husbands’ most trusted advisers. Hopefully, the country is ready for a first lady who is many things, like so many women in this country: a professional, a mother, a wife, and a grandmother. After all, a job with no set definition should be open to change.