Her world ended when her kids were murdered. Raising dozens of orphans saved her life

Updated 1446 GMT (2246 HKT) August 17, 2018

CNN is committed to covering gender inequality wherever it occurs in the world. This story is part of As Equals, a year-long series.

Rubona, Rwanda ŌĆö As a cacophony of birdsong greets the rising sun, Mama Marie Goretti Amurere corrals her daughters from their beds and out the door of their single-story home.

By 6am, Goretti, 60, walks the path from her house to the canteen, flanked by her girls and a lush perimeter of banana trees extending to a horizon of hills.

Inside the cafeteria, she pours rounds of igikoma, a millet porridge, into small plastic cups; it's eaten with fluffy white bread rolls that pass along the communal table. As her bleary-eyed teenagers eat their breakfast, Goretti watches the clock. School starts at 7 a.m. and it's a ten-minute walk up the hill.

It's a morning routine familiar to mothers around the world, but these aren't Goretti's biological children.

Goretti's husband and three of her five children were among 800,000 people killed over the course of 100 days during Rwanda's 1994 genocide.

When the genocide ended, she felt her life was over, but more than 20 years on and with dozens of children calling her "Mama," she says she has a reason to live.

Goretti is one of 28 "Mamas" who live and work at the Agahozo Shalom Youth Village (ASYV), a holistic, educational oasis in Rwanda's lush Rwamagana district, 50 kilometers east of the capital, Kigali.

The village is expansive, with 30 family homes, extracurricular buildings and guest houses laid out in a series of concentric circles across 144 acres.

"I felt it was an honor for me to hear these children call me mom," Goretti, now in her eighth year at ASYV, says.

Derived from a mix of the local Kinyarwanda language and Hebrew, its name translates as "a peaceful place where tears are dried."

The village is modeled after an Israeli youth village -- a family-structured center established after World War II for children orphaned during the Holocaust. In 2008, ASYV opened its gates to its first group of children, some of the country's most vulnerable orphans.

More than 520 orphaned and disadvantaged teenagers live and study there. Structured around the family unit, groups of 16 to 24 children live among each other as "siblings" in a home headed by a "Mama."

Most of the Mamas are widows and have lost at least one child as a direct or indirect result of the genocide.

Goretti's path to the village wasn't an easy one. Taking on a job that held a title with so much meaning dredged up memories from the darkest moments of her life, which she had tried to bury.

In the April of 1994, Goretti received a chilling phone call after returning home from the post office where she was working as a clerk. The man on the line told her: "They are coming for you, they're going to kill you. You're going to die tonight."

Over the next three months as the genocide unfolded, Goretti saw one daughter killed in front of her and her eldest son beaten within a breath of his life. She hid out in cornfields as she prayed for the children she had been separated from.

Each night through the stalks of maize, the genocidaires, or killers, would announce who they had killed. When Goretti learned that her son and another daughter, her eldest, had been murdered, she emerged from her hideout, ready to die.

"I came out of hiding... but they refused to kill me. They started piercing me with spears all over my head -- they were wanting me to have an emotional reaction, but I wouldn't give it to them. I just stood still," Goretti recalls.

Goretti eventually returned to her hiding place until the violence ended in July 1994.

"We were happy to feel saved even though we had nothing really -- we were really tired and we were looking forward to dying. We were just tired of being in this life," Goretti says.

That sentiment shifted when she learned her two youngest children had survived. They were found in a refugee camp in neighboring Burundi and eventually returned to live with her.

Goretti decided to foster orphans into her home, including those whose parents had been perpetrators of the genocide. It was her duty, she says.

"I felt an obligation to care for them the same way other people would have cared for our own children had we died," Goretti explains.

She provided for some 25 children -- in addition to her two youngest children who survived the genocide -- until 2010.

"The gift I could give to my family that died was raising other children, any child that would come to me," Goretti says.

When the youngest of those orphans was ready to live on their own, she joined ASYV. It was there that she began to heal herself, she says.

The Mamas live with the children throughout their four-year tenure and are the backbone of the village. They provide emotional and logistical support to their children.

After classes are done for the day, Goretti gathers with her girls in the living room of her house for an hour of "family time," a nightly session where families share moments from their day and talk through problems.

There's ample time for song, prayer and dance. Ed Sheeran's ballad "Perfect" has become a sing-along staple in the village.

Goretti says her work is not a job.

She doesn't clock in or out. And her shift doesn't end when the kids fall asleep.

"It is a calling. If you come here just for a job, you would simply quit, because it's very difficult to raise children who are not your own, especially when they come from traumatic circumstances. If it wasn't a calling, you would not be able to cope," Goretti says.

When ASYV first opened its doors, the children there had all been orphaned by the genocide. They carried the trauma and pain of a nation. Others were born as a result of rape. An estimated 250,000-500,000 women were raped during the genocide, with some 20,000 children born as a result of that systematic sexual violence, according to the British charity Survivors' Fund.

It's been 24 years since the genocide -- and like Rwanda, the student body continues to evolve. The village now sees children from disparate backgrounds, but they all share an understanding of loss.

Some of the village's current students have been orphaned from retaliatory violence that occurred after the gacaca process -- village tribunals set up to prosecute suspects of the genocide. Other children come from single parent homes who can't afford to send them to school, one indication of the poverty that continues to plague more than 51% of Rwanda's population, according to the World Bank's 2018 projections.

Goretti believes Mamas like herself -- women who have harnessed an inner strength from tragedy -- hold the key to Rwanda's future generation.

In the wake of the genocide, the demographics of the nation dramatically changed. Losing a generation of men skewed the population to 70 percent female and more than 95,000 children were left orphaned.

"Women are heroes... men would have never been able to care for the children as we did. We took it upon our responsibility to take all the kids who had survived to bring them into us," Goretti says.

She says she has now has found self-healing in those relationships. Connecting with children with "the same wounds" of loss has helped her to move past trauma and reshaped her role as a mother.

Titui Martine, 17, one of her Goretti's village daughters, says her Mama is a "gift from god," and that her story has helped her to move past her own trauma.

"She's showed me how we have to live our life now -- not focusing on the past," Martine says.

"It's just the past and it won't come back. Her life was really hard so I had to really understand that."

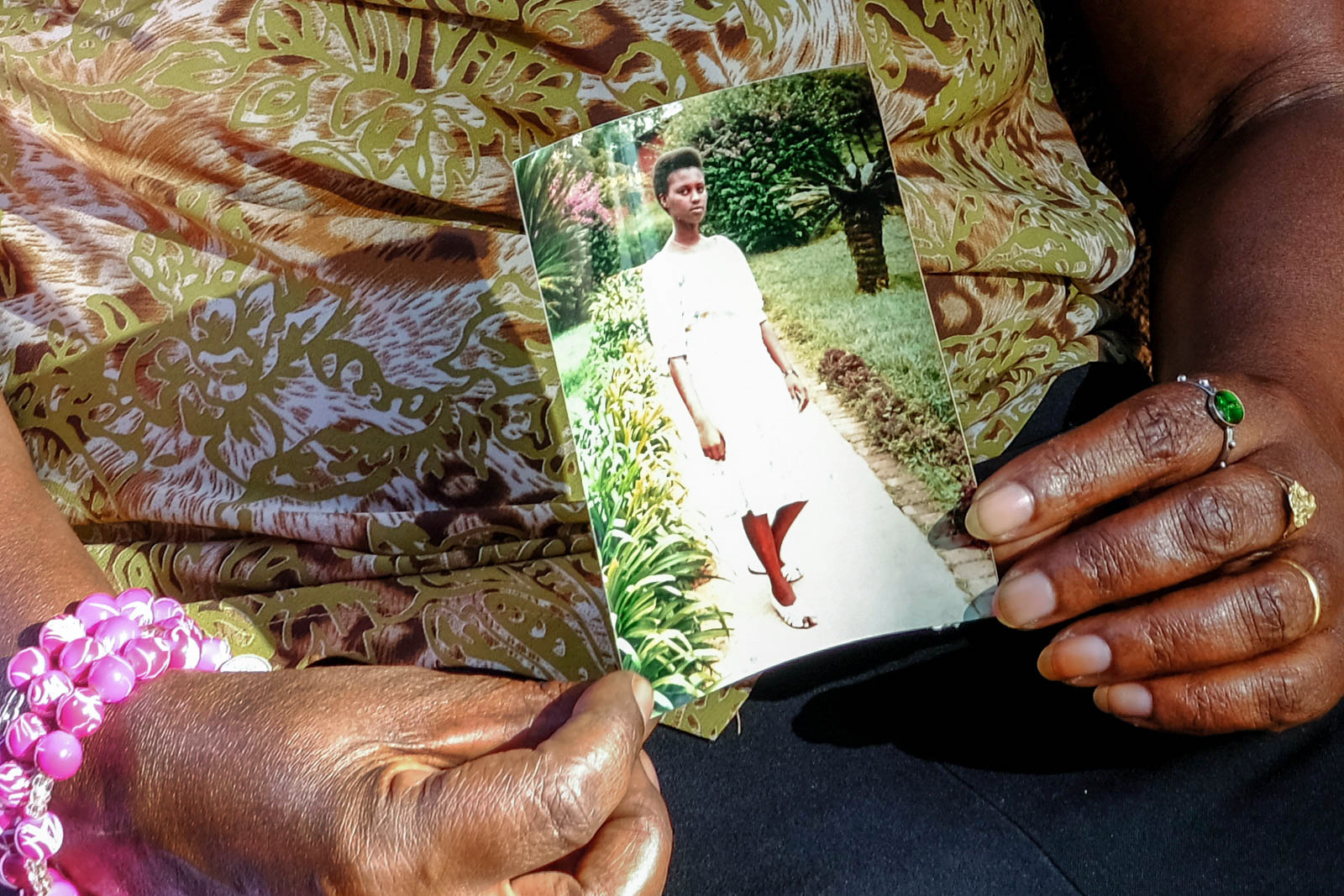

Inside Mama Goretti's house the remnants of the past are never far. She keeps a photo of her eldest daughter in her purse.

"Outside people believe I am strong, but that's not true. It would be a lie if I told you I have overcome the loss of my children," she says.

But she also chooses to focus on the future, pointing to a mug gifted to her by her girls. When the mug is filled with water, her picture appears.

"They make me forget my own suffering, for a short while. I think that's what makes me happy."

The As Equals reporting project is funded by the European Journalism Centre via its Innovation in Development Reporting Grant Programme. Click here for more stories like this.