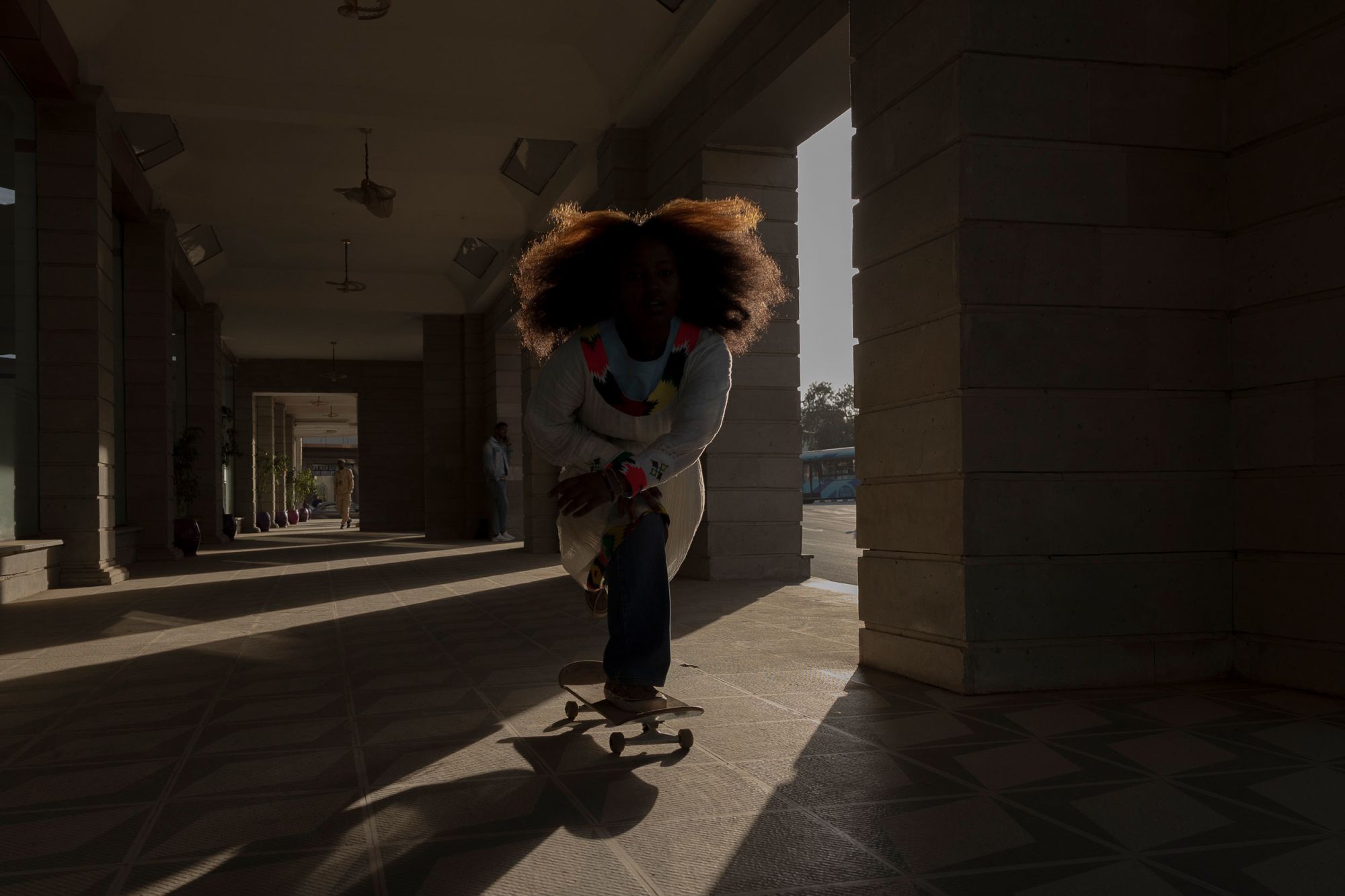

Makdelina Desta, one of the founders of the group known as Addis Girls Skate, hangs out with her friends in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

These female skateboarders are shredding stereotypes in Ethiopia

Photographs by Chantal Pinzi/Panos Pictures

Story by Kyle Almond, CNN

Published October 19, 2025

Makdelina Desta, one of the founders of the group known as Addis Girls Skate, hangs out with her friends in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Edomawit Ashebir tries to block out the haters.

Every time she grabs her skateboard and goes out in public, the young Ethiopian knows she might hear some rude comments.

“My mom empowers me, but people in the street are against it,” Ashebir told documentary photographer Chantal Pinzi. “There’s a guy talking sh*t: ‘You’re an idiot. You’re causing problems for your family. You’ll never achieve anything in life. You’re a girl. What are you doing on the street?’ ”

Remarks like these aren’t uncommon when Ashebir and other members of her all-female skateboarding group go out in the Ethiopian capital.

But they won’t be deterred. They have the support of a growing skate community in the country.

And most of all, they have each other.

Ethiopia is rebuilding after a devastating civil war that ended in 2022. The capital, Addis Ababa, is changing at a rapid pace, Pinzi says, with new skyscrapers and infrastructure transforming the city skyline.

But inequalities remain and there are still deeply rooted patriarchal expectations and gender roles. “In the public space, it’s still really rare to see women,” said Pinzi, who visited the African country earlier this year.

So when Ashebir and her friends grab their skateboards, there’s a much deeper significance.

“The new generation, they don’t see skateboarding only as a sport. They also see it as a place of equality and freedom,” Pinzi said.

Makdelina Desta is one of the founders of the group known as Addis Girls Skate. She told Pinzi that, to her, skating basically means freedom.

“As a girl, you carry so much responsibility. You can’t just be with your friends without worrying about something,” she said. “But when I skate, I’m not pretending to be someone else. That’s when I’m truly myself. I don’t feel judged.

“At the skate park, we all share the same mindset, even though we come from different places and have different stories. We inspire each other, and that makes me feel free.”

Those feelings are echoed by Ashebir.

“When I skate, I forget all the problems at home,” she said. “I don’t feel the pressure from my parents anymore. It’s a way for me to feel free and escape everything.”

Every Saturday, the small but determined group of young women meets at a skate park in Addis Ababa.

It’s one of only a few skate parks in the entire country — and on Saturdays it is reserved just for them.

Here, these teenage skateboarders are able to try out new tricks, express themselves and have fun with friends they wouldn’t have made otherwise. They’re also getting a chance to redefine their identity.

“They are kind of reshaping the future that they see for themselves — not what was already written for them,” Pinzi said.

Pinzi’s photos show the young skaters at the park as well as on the streets — turning heads in Merkato, Africa’s largest open-air market, and flying down Mount Entoto at high speeds with the wind in their hair.

“I’m in love with the sound of the wheels on the concrete. It’s like hypnosis,” one group member, Lydia, told Pinzi. “I forget everything and stay calm.”

In many of the photos, they’re wearing traditional white dresses known as habesha kemis, which Pinzi says they love wearing. In other photos, they wear school uniforms or more casual clothes that wouldn’t look out of place in any skate park around the world.

Pinzi also hung out with the girls as they bonded away from their boards — sharing food, watching sunsets, combing one another’s hair.

“Many of them, they were feeling lonely as teenagers,” Pinzi said. “What skateboarding brings them is a really strong sisterhood and the support of a community that they feel that they belong to.”

The men and boys in the Ethiopian skate community have also been very supportive, Pinzi said, and they share the skate park with the girls on other days of the week. The male skaters will often encourage the girls and push them to be better. They’ve even provided some of them with equipment.

But away from the skate park, not everyone is as accepting.

One skater, Tsion, told Pinzi that “people in the street are waiting for the moment I fall, just to feel they are right in thinking I’m doing something stupid, something that doesn’t belong to me and that I shouldn’t be doing as a woman.”

Pinzi saw one man pass the girls and call them “the devil.”

“The girls looked at him and ignored him, but they are there for each other. That is the most important thing,” she said. “They don’t care so much. (People) can say whatever they want, but in the end, (the girls) are together. They support each other, and that’s what really counts for them.”

Not all of the skaters in the group are teenagers. Burtekan, a 43-year-old single mother of two, has also joined up.

“I wake up in the morning with the goal of breaking all my limits,” she said. “They shout at me that I’m too old and not to fall. I may be old, but I’m not dead. I still have a lot to give.”

The skate community calls her “Mamy” and embraces her courage with open arms.

Pinzi said that for many Ethiopian women, once they get married it’s like they don’t exist anymore outside the house — once they get married, they stay at home.

Not Burtekan.

“She’s doing something really different,” Pinzi said. “She skates because she wants to break those stereotypes. Even if she has two children, she also wants to have free time for herself.”

Ethiopia is the third country that Pinzi has documented for her long-term project she calls Shred the Patriarchy. She has also photographed female skateboarders in Morocco and India.

“I’m an athlete myself. Apart from skateboarding, I also do martial arts and I fight. So I was interested in seeing how sport exposes structural inequality in society,” she said. “I also want to expose injustice.

“Sports can provide empowerment. I see the power of sports and how, mentally and physically, they can really empower women. In many countries, participation is still limited.”

While each country she visited has its differences, she noticed that all the skateboarders she met had something in common.

“I could see how different these women are from the rest. They are really empowered. They look you in the eyes. You can see their self-confidence. For me, that makes skateboarding really special and important.”

While the skate scene in Addis Ababa is growing, there is still much work to do outside the capital. In the more rural areas to the south, it’s rare to see a female skater, Pinzi said.

She photographed what she said was the only female skater in the city of Hawassa — a girl named Shurrube.

Pinzi said Shurrube is one of the strongest female skaters she met in Ethiopia, but Shurrube couldn’t skate for more than two months because she didn’t have a working board. Pinzi brought her a new deck when she arrived.

“It’s a pity, because she has so much potential but not so many resources unfortunately,” Pinzi said. “She’s really talented.”

Every time Pinzi visits a new country, she tries to give back to the community. She asks for donations from her skating community in Berlin — old boards or materials she can bring with her and repurpose. She always receives a large amount of boards.

She is inspired by the sport and the universal life lessons it can teach to people all over the world.

“I have experienced this deep personal impact that skateboarding can have,” she said. “It’s not only landing the trick that is magical itself. Skateboarding teaches you how to never give up, and that’s something that you can use in your daily life, too. …

“Skateboarding doesn’t really care about where you come from or who you are. The main thing is that you kind of keep pushing forward.”