The forgotten men and women of our country will be forgotten no longer.

—Donald Trump, in his victory speech, just before 3 a.m., November 9, 2016.

Almost everyone thought he would lose. Clinton did. Her vaunted political operatives did. The pollsters did. The #NeverTrump Republicans did. For all his bluster and bold predictions of victory, Trump himself had been worrying all day. He kept pressing aides for information, but they were worried, too. Even his internal models showed him falling short of the 270 electoral votes needed to win.

But as the night went on, strange and unexpected numbers flashed across the television screens of America. Early returns put Trump ahead by 3 points in Florida, 10 in Ohio and North Carolina. Virginia was not supposed to be competitive, but Trump had an early lead there, too.

"There isn't panic," a Clinton aide said around 8 p.m. Then it was 9, and 10, and the numbers held in Florida and Ohio, and now Trump was leading in Michigan and Wisconsin. Could he crack the Democrats' so-called Blue Wall in the industrial Midwest? Clinton's aides doubted it. They thought he'd missed his chance in Michigan by not campaigning much there until the end. Clinton was so confident about Wisconsin that she never campaigned there at all. She was not so sure about Pennsylvania, which is why she'd hit Philadelphia three times in three days and visited Pittsburgh the previous morning. But now, even in Pennsylvania, her lead narrowed as the night went on. Five points, 4, 3. Something was happening out there, a seismic disruption whose foreshocks nearly all the experts had ignored. By 10:04 p.m., Dow futures had plunged by nearly 500 points. And the wildest campaign in modern history appeared to have one more astonishing twist.

As it turned out, the experts' combined wisdom was no match for that of Dave Calabro, also known as Jersey Dave, a 57-year-old South Philadelphian and Trump supporter who thought America had lost its way. He'd acquired his nickname by selling Eagles jerseys in sports bars to provide for his family. He did not always drink beer, but when he did, he usually drank Coors Light. He yelled BLUE LIVES MATTER to cops on Broad Street. He used to love Bruce Springsteen, but now he thought the Boss had disgraced himself by supporting Clinton. Jersey Dave Calabro said it that summer, and kept saying it until Election Day: Trump would carry Pennsylvania, which no Republican had done since 1988, and he would be the next American president.

"The guy never loses," Calabro said.

There were two Americas in 2016. One had been advancing for a long time. One had been retreating. And on November 8, Trump and his army of Jersey Dave Calabros found a way to reverse the trend.

The two Americas were nearly a century in the making. They resulted from women's suffrage, the civil rights movement, the women's rights movement, the gay rights movement and a Hispanic population that increased by roughly 50 million in the last fifty years. These changes had two things in common: They gave power to those who previously had little or none. And they diminished the supremacy of straight white men.

Clinton's America was a coalition of these historically disadvantaged groups, along with their white male allies. Year by year, it seemed to align more closely with large corporations and the global elite. It was urban, ascendant, seemingly unstoppable.

Its inhabitants saw the last hundred years as a good start, an unfinished march of societal progress. Yes, the nation had same-sex marriage, an African-American president and a number of female chief executives, but this America still felt itself chafing against systemic inequality. Did racism, sexism and homophobia still exist? Of course they did. Clinton's America wanted them eradicated.

Trump's America drew in some women and minorities. But much of its energy came from white male grievance. Factories had been closing for decades. Many manufacturing jobs had moved overseas or given way to automation. As wages stagnated, more and more blue-collar men felt themselves working hard and going nowhere. They felt abandoned by the new information economy, swindled by Washington politicians, stifled by the new cultural orthodoxy. Certain men of Trump's America were thrilled when he said, "Frankly, if Hillary Clinton were a man, I don't think she'd get 5 percent of the vote." These men were tired of being blamed for the sins of their fathers, sick of hearing the phrase white guy thrown around like an insult. Wasn't that racism, too? Couldn't there be sexism against men? They felt as if the people of Clinton's America had overtaken them somehow, probably by cheating.

"I know I'm the projection for many of those wounded men," Clinton once said, as quoted in "Hillary's Choice," a 1999 book by Gail Sheehy. "I'm the boss they never wanted to have. I'm the wife they never—the wife who went back to school and got an extra degree and a job as good as theirs....It's not me, personally, they hate—it's the changes I represent."

A year before Clinton's campaign officially began, two allies were emailing about strategy. "In fact, I think running on her gender would be the SAME mistake as 2008, ie having a message at odds with what voters ultimately want," Robby Mook, her eventual campaign manager, wrote in a message later hacked and released by WikiLeaks. "She ran on experience when voters wanted change.…It's also risky because injecting gender makes her candidacy about HER and not the voters and making their lives better."

But Clinton's America wanted to rally behind the woman who could bring societal progress to its next logical step. If she won, they would all win, at least symbolically, and so the campaign adopted the slogan I'm With Her. On the day she testified before the House Select Committee on Benghazi in October 2015, online appeals using this slogan helped her raise $133,000 in a single hour.

"I don't want you to vote for me because I'm a woman; I want you to vote for me on the merits," she said that year. "But one of my merits is that I'm a woman."

Early in 2016, her campaign chairman, John Podesta, received an email that was later released by WikiLeaks. "I'm a dinosaur to the Democratic Party…white, southern, veteran, male senior," wrote Dana Folsom of Augusta, Georgia. "...I would like to have my ilk shown a tiny bit of respect by the leaders of the Hillary campaign."

"You've earned that respect and we'll try to show it," Podesta replied.

Was Clinton's America big enough for men like Dana Folsom? He did vote for her in the Georgia primary. She added other slogans, such as Fighting for Us and Stronger Together. Still, many blue-collar men were suspicious. Fighting for Us sounded like fighting for the people who were not them, rallying those people against them, and Stronger Together still evoked the progressive union against the way things used to be.

Unprecedented 2016

Phil

Mattingly

A failure to see the obvious

"I'm with you," Trump said, and they liked that more than I'm With Her. Her aides marveled at the reams of negative stories about Trump that had no effect. Decorated generals and establishment Republicans joined forces with Clinton to tell the men of Trump's America they were making a huge mistake. But the men ignored the message, because they distrusted the messengers, and because, like Trump, they hated being told no. These rugged individualists who felt their country being stolen were not about to "listen to reason" from those they suspected of committing the theft. No, you can't elect someone like Trump? Their campaign slogan might as well have been Yes I Can.

You can't vote for a man who insults women and immigrants and Muslims and people with disabilities.

Yes I can.

You can't vote for a man who boasts about sexually assaulting women.

Yes I can.

You can't give the nuclear codes to a man who might blow up the world because someone looked at him sideways.

Yes I—

✦ ✦ ✦

Trump's campaign had been declared dead in August, and again in October. Now, if he could somehow control himself, he had a chance to win. "Stay on point, Donald," he said aloud at a rally on November 2. "Stay on point."

In the last week of the campaign, he was narrowing the gap. Polls showed him leading in some battleground states, drawing closer in others. Regardless of his intentions, James Comey's letter had given Trump a gift. It had helped unite Republicans against Clinton.

Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid of Nevada said Comey may have violated the Hatch Act barring political activity by federal employees. Three former U.S. attorneys general, including two who served under George W. Bush, lashed out at Comey for writing the letter so close to the election. Thirty-six former state attorneys general signed a statement saying Comey's letter contained "unfair speculation and innuendo." His letter infuriated and terrified Clinton supporters, some of whom believed it would cost her the election. When it was over, a top Clinton aide would say it had.

Two days before the election, on Sunday, November 6, Comey sent Congress another letter saying the Clinton email investigation was closed again, meaning that she was once again in the clear.

✦ ✦ ✦

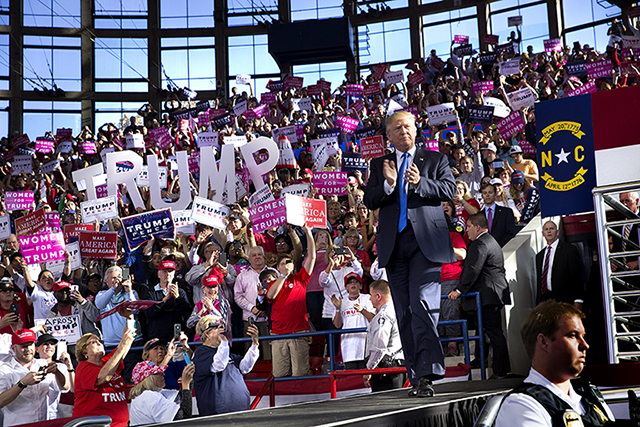

The sky was clear in Florida the final weekend of the race. Inside a warehouse at the state fairgrounds in Tampa, Trump convened his first of four rallies. A sign in the crowd said DOWN WITH THE SWAMP WITCH.

He went on to an airport hangar in Wilmington, North Carolina, where two small boys wore rubber Trump masks. "As you know," he said, "the FBI has reopened its criminal investigation of Hillary Clinton." This hyperbole led to chants of LOCK HER UP, LOCK HER UP, and a woman near the press riser said, "Put Obama in there with her." A pale crescent moon hung behind the stage. "We're winning," Trump said. "We're winning everywhere."

Analysts thought he was wrong, and that was fine with him. (The polls had also failed to predict Brexit, the United Kingdom's surprising choice that year to leave the European Union, and Trump liked to call himself "Mr. Brexit.") Even some operatives in his party thought he was running a terrible campaign: no organization, no ground game, no clue.

"We made a conscious decision to let that narrative continue," his deputy campaign manager, Michael Glassner, said in an interview, "because we believed that it was in our interest for them to underestimate us."

After Mitt Romney fell short in 2012, Republican National Committee Chairman Reince Priebus vowed not to let the Republicans get out-hustled again. The RNC spent more than $175 million to improve its ground game. They had a file of 197 million voters, each scored on a hundred-point scale for their likelihood to vote Republican. And the RNC deployed all these weapons in the service of Trump. Five days before Election Day, the RNC's models showed Trump winning Michigan by two-tenths of a point.

He left Wilmington and went on to Nevada. Inside the Reno-Sparks Convention Center, where a young woman wore a pink hat that said DEPLORABLE, he continued his assault on Clinton.

"We didn't bring any so-called stars along—we didn't need them," he said, referring to the bevy of celebrities, from Jay-Z to Lady Gaga, who campaigned for Clinton in the final days. Her dazzling cast of surrogates included both Obamas, her ex-president husband, Vice President Biden and her former opponent, Bernie Sanders. In 2016 Trump ran against the Democrats, the Republicans, two political dynasties and the last three presidents. Through the force of his personality, he would defeat them all.

Trump would not win by mobilizing an unprecedented coalition of Republicans. (Indeed, at the time of publication, Clinton held a lead in the nationwide popular vote.) He would win because Clinton underperformed Obama's showing in 2008 and 2012.

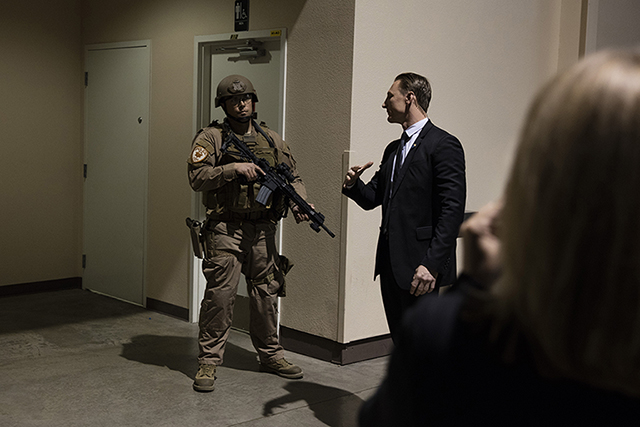

There were chants of U-S-A and LOCK HER UP, and it seemed like a normal Trump rally until someone yelled something about a gun.

The sequence began when Trump noticed a protester in the crowd. "Oh, we have one of those guys from—from the Hillary Clinton campaign," he said. "How much are you being paid? Fifteen hundred dollars?"

He paused, shielding his eyes, looking back into the crowd. Two Secret Service agents ran onto the stage. "Go, go," one of them said, hustling him behind the curtain. People ran for the exits. Officers in tactical gear ran toward the stage. The officers led a man out of the room. The crowd went wild, chanting U-S-A again. The stage was empty for almost four minutes. Then Dan Scavino, Trump's director of social media, took the microphone.

"NOBODY IS GONNA STOP THIS MOVEMENT!" he shouted.

Trump swaggered back out. He let the applause wash over him.

"Nobody said it was going to be easy for us," he said. "But we will never be stopped. Never, ever be stopped."

The authorities never found a weapon. No arrests were made. Nevertheless, both Scavino and Donald Trump Jr. retweeted a Trump supporter who said, referring to Clinton's rain-shortened rally in Florida, "Hillary ran away from rain today. Trump is back on stage minutes after assassination attempt."

The violence that attended the 2016 campaign was unlike anything the nation had seen since the 1960s. There were victims and perpetrators on both sides, although markedly more on the Trump side. Left-wing protesters attacked Trump supporters, stealing their MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN hats and setting them ablaze. Someone fire-bombed a Republican Party office in North Carolina. In Mississippi, someone torched an African-American church, leaving the words VOTE TRUMP on the side. And some Trump supporters hinted at further violence if Clinton was elected.

"On November 8th, I'm voting for Trump," former Congressman Joe Walsh tweeted. "On November 9th, if Trump loses, I'm grabbing my musket. You in?"

It was an unsettling question, contrary to all protocols of American democracy. But it would be left unanswered.

✦ ✦ ✦

I late July, Clinton visited Johnstown, Pennsylvania, a desolate city of 20,000 whose welcoming committee included the bearer of a sign that said KILLARY KILLED COAL. Inside Johnstown Wire Technologies, where fine gray dust covered the surfaces, Adam Wisniewski said Johnstown had been so poor for so long that it barely felt the effects of the 2008 recession. He was 38 years old, delivering caskets part-time, and he knew people who sold food stamps to buy sports equipment for their children.

Bill Clinton's America once included Johnstown. When he ran for re-election in 1996, the Man from Hope won almost every state in Coal Country and the upper Midwest. Labor unions were stronger then, factory jobs more plentiful, blue-collar white workers more inclined to vote Democratic. Johnstown is in Cambria County, which Bill Clinton won with 51 percent of the vote that year. Twenty years later, this county would help give the presidency to Trump.

Hillary Clinton knew she had to reach some of these white working-class voters, but she went about it awkwardly. During a CNN town hall in Ohio on March 13, she was talking about renewable energy and said:

"…We're going to put a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of business, right? And we're going to make it clear that we don't want to forget those people....Now we've got to move away from coal and all the other fossil fuels, but I don't want to move away from the people who did the best they could to produce the energy that we relied on."

What did people remember from that statement? We're going to put a lot of coal miners out of business.

"Her point was, 'I have a plan to help coal miners transition to a new economy,' Clinton's director of speechwriting, Dan Schwerin, said in an interview. "More than anyone else in the campaign, she has cared and thought about how we can get to working-class white voters in places like Appalachia. It's just a cruel irony that her passion for this subject led to that; it came out in the wrong way with that comment."

Unprecedented 2016

Daniella

Diaz

A clash of identities

Trump kept it simple. Signs at his convention said TRUMP DIGS COAL. He ran against both Clintons, blaming them for the free-trade agreements that he said were responsible for massive job losses. Their overall effect was closer to neutral, but KILLARY KILLED COAL had a nice ring. When Clinton visited Johnstown, the Trump campaign released a statement comparing it to a "robber visiting their victim." Could Trump actually bring jobs back to Johnstown? Adam Wisniewski didn't think so. To him, Trump's promise was just another drug, like the opioids that killed fifty-three people in Cambria County the previous year.

"People feel so lost today," he said. "They would rather just take the magic pill and go back to sleep."

All across the industrial Midwest, Hillary Clinton lost counties that had previously voted for Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. She lost Cambria County by 38 points, and she lost Pennsylvania.

✦ ✦ ✦

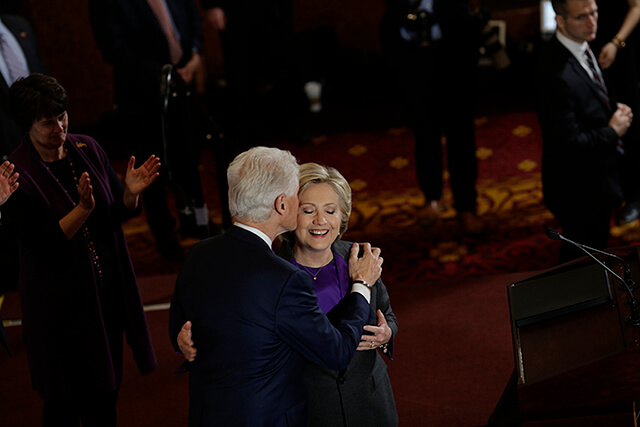

She had two speeches written, just in case, and as the first results came in she was reviewing them at the hotel suite in Manhattan. Her top aides were there, along with Bill and Chelsea and the grandkids. There was salmon with roasted carrots on the buffet in the hallway, vegan créme brûlée for dessert. The concession speech was a precaution from a woman who liked to be prepared. A mile and a half away at the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center, other staffers prepared for a victory party. The building had an actual glass ceiling. Cannons would fire green-tinted confetti that resembled shattered glass.

"Thinking about my daughter right now," a confident Tim Kaine tweeted at 8:30. "No little girl will ever again have to wonder whether she, too, can be president."

Clinton's own mother had been unwanted by her parents. Left to roam the streets of Chicago at age 4. Sent to live with her cruel grandmother at age 8. Turned out on her own at age 14. Her name was Dorothy. She got married, had children, spent her life giving them the home she never had. She took a break from hanging up the clothes to lie in the grass with her daughter and look up at the clouds. Dorothy Rodham died in 2011 at age 92, five years too early to witness this night. Her daughter was running for president a second time, and once again she would come up short.

At 11:07 p.m., CNN projected the battleground of North Carolina for Trump.

Around 11:20, a young Clinton staffer wiped away tears.

Around midnight, with Clinton still sequestered in the hotel, people began leaving the Javits Center. At a bar nearby, a man lay on the floor and wept.

The returns kept coming in. Experts had expected Trump to lose, and to drag other Republicans down with him, costing them the Senate and drastically reducing their majority in the House. Instead, his long coattails helped them keep control of both chambers. The experts had been talking all year about chaos in the Republican Party, but it was the Democrats who had fallen apart. Obama's legacy was now in jeopardy, his many executive orders subject to nullification by President Trump, his signature health-care law in danger of being scaled back if not repealed altogether. The new president might choose as many as three or four Supreme Court justices, thus shaping the high court for decades to come and putting Roe v. Wade in question.

The Democrats had a candidate who connected with the angry white worker. Some of his rallies were even larger than Trump's. In the primaries he defeated Clinton in both Wisconsin and Michigan, hinting at the vulnerability of her Blue Wall. Head-to-head polls in May showed him leading Trump by as many as 15 points. But the Democrats nominated a status quo candidate when many voters desperately wanted change. And the Clinton campaign ignored the lessons of the primaries, essentially deciding to ignore Wisconsin and avoid Michigan as long as Trump did.

Midnight turned to 1 and 2, with Clinton nowhere to be seen. The race had not been officially called, but it was clearly over. Her campaign chairman, John Podesta, addressed the weary faithful at the Javits Center.

"Several states are too close to call," he said on live television, provoking chants of LOCK HER UP at the Trump victory party about twenty blocks away. "...You should get some sleep."

Shortly after 2:30 a.m., Clinton called Trump to concede and offer congratulations. CNN called the race at 2:48. Trump took the microphone at 2:49 to chants of U-S-A. Despite his many previous threats, he said nothing about locking her up.

"Hillary has worked very long and very hard over a long period of time, and we owe her a major debt of gratitude for her service to our country," he said. "I mean that very sincerely. Now it's time for America to bind the wounds of division; have to get together. To all Republicans and Democrats and independents across this nation, I say it is time for us to come together as one united people."

For all the uproar over the racial tension he stirred, exit polls showed that Trump captured 8 percent of the black and 29 percent of the Latino vote, slightly better than Romney had in 2012. Clinton could not quite re-create the Obama coalition. She fell short among both minorities and young voters, as well as white working-class voters in the Midwest.

And while she won women overall by 12 points, she lost white women by 10 points.

Later, Clinton's allies would blame Comey for lower-than-expected turnout—and for her loss. They had seen encouraging trends in early voting before October 28, particularly among minorities. But on Election Day itself, Clinton did not hit her targets.

"If you were on the fence, and you were repelled by Trump and open to her, and the Comey letter happens, and you were reminded of the emails, a lot of people decided, 'Never mind,'" a senior adviser told CNN, speaking on condition of anonymity. "And it killed the mood among minority voters."

Next morning she had to face the cameras. At a ballroom in the New Yorker hotel, nearly all her top aides teared up. Her husband worked the rope line, wiping away tears. This would be one of the hardest things she had ever done.

A concession speech can be more important than a victory speech, and this concession speech was more important than any in recent memory. Clinton had just lost to a man she considered temperamentally unfit for the presidency. Her political career was probably over. The hopes of tens of millions of women were dashed. "A piece of me died last night," her supporter Ruth Ellis wrote in an email. Clinton had come so far, gotten so close, and it might be a long time before voters gave a woman another chance. Her own mother had died waiting for the first woman president, and no one knew how many others would do the same. She said the glass ceiling would shatter one day, a reference to her concession speech from eight years earlier. She told her followers not to lose heart. And she told them to give Trump a chance.

"Last night, I congratulated Donald Trump and offered to work with him on behalf of our country," Clinton said. "I hope that he will be a successful president for all Americans."

She lingered on the word all, making the emphasis unmistakable. It sounded like a challenge, and maybe a prayer.

Protests broke out that night in several major cities. In Los Angeles, young Latinos kindled a piñata in the shape of Trump's head and chanted, NOT MY PRESIDENT! NOT MY PRESIDENT! But he was, or would be soon. He would not just preside over the roughly 60 million people who voted for him. He would preside over the slightly larger number who did not. He would preside over the flag-wavers on the plains of Iowa and the flag-burners on the streets of New York. He would preside over Jersey Dave Calabro, Khizr Khan, the young men and women in Los Angeles who gave his effigy a crown of fire. Now he had the power he wanted. It was time to bring together the nation he had helped to drive apart.