11 bodies, one house of horrors: Why Cleveland women were 'invisible'

- A year later, families in the Cleveland area continue to mourn the death of 11 women

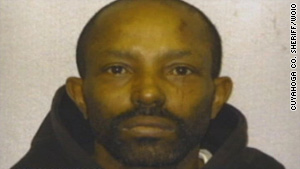

- Anthony Sowell, 51, who will go to trial in February, allegedly killed the women in his home

- The body of Tonia Carmichael, 52, was one of the first to be discovered last year

- Criminologists say serial killers often target vulnerable women such as prostitutes and drug users

Cleveland, Ohio -- Nine-year-old Jonathan Carmichael thought his mother was Superwoman.

He observed her unstoppable force, working double shifts as a medical secretary so they could live in a modest town house in a decent neighborhood. He saw her fly off to do overtime, and then surprise him and his sister with toy cars and video games and a trip to Disneyland.

But by the time he was 12, his super mother had vanished, replaced by a crack cocaine addict. He watched her pawn the gifts she'd bought him to feed her habit.

If Jonathan felt confused, his sister Donnita was angry. She was 18 when the mother she once knew went missing. Donnita loved her and she hated her. She argued with her and listened to her. She tried desperately to save her from her addiction. And when she failed, she stopped calling her "Mom."

Sometimes, their mother, Tonia Carmichael, disappeared for days or weeks at a time. So on November 10, 2008, when her children heard she was missing, it seemed, sadly, like nothing new.

She was gone.

So were Crystal Dozier, 38, and Tishanna Culver, 29.

And Le'Shanda Long, 25, and Michelle Mason, 44.

They were all black women with ties to the quiet neighborhood of Mount Pleasant in the eastern part of Cleveland. They were all mothers, some grandmothers, some second cousins. Almost all struggled with a drug addiction at some point in their lives. Court records show many resorted to stealing and some turned to prostitution to support their habits.

Six more women would disappear after 52-year-old Tonia:

Kim Yvette Smith, 43.

Nancy Cobbs, 43.

Amelda Hunter, 46.

Telacia Fortson, 31.

Janice Webb, 48.

Diane Turner, 38.

When police found their bodies in October 2009 -- all on one man's property -- everyone wondered: How could 11 women in the same town disappear over two years without public notice?

Tonia's body was the first to be identified in what locals soon dubbed the Cleveland house of horrors. Her remains were unearthed from a shallow grave in the backyard, decayed beyond recognition, except for plastic jewelry falling off her skeletal fingers.

Police believe the women were easy prey for Anthony Sowell, a convicted sex offender who served 15 years for the attempted rape of a woman in 1989. Sowell, now 51, had moved to the home on Imperial Avenue in 2005, after his release from prison.

He has been charged with 11 murders, two rapes, one attempted rape and more than 70 other related charges. He has pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity and is scheduled to go to trial in February 2011, according to the prosecutor's office. His lawyers declined to comment for CNN or let Sowell be interviewed.

2009: Sowell appears in court

2009: Sowell appears in court

2009: Suspected serial killer in court

2009: Suspected serial killer in court

"We feel his Miranda rights were violated," one of Sowell's attorneys, John Parker, told the Cleveland Plain Dealer after a hearing in January. "He was interviewed by police at great length. I have seen videotape of the interrogations and I have asked that it be excluded."

Since the bodies were discovered, other women have come forward, alleging Sowell attacked them. His attorneys would not comment on those allegations either.

Criminologists say serial killers often target people whose lives may be messy or off the grid -- prostitutes, runaways and drug users -- because their absences might not raise red flags, even for their families.

Sometimes members of the public blame the victims in these cases for living a vulnerable and dangerous lifestyle, said Jack Levin, a professor of sociology at Northeastern University who specializes in studying serial killers. And certainly some observers vilified the "Imperial 11" as drug users and criminals. But family members and friends say their stories are far more complicated.

For instance, 31-year-old Telacia Fortson, a mother of three, was living in a shelter and trying to stop using. Church members say she attended St. Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ, a block from Sowell's house, for six Sundays in a row before she disappeared.

Some observers suggest the location of the crimes explains why the bodies went overlooked.

Sowell's inconspicuous two-story home sits in a dilapidated neighborhood known as Mount Pleasant, where one in five homes are in foreclosure and at least a third of the residents receive food stamps, according to a study by Case Western Reserve University's Center on Urban Poverty and Community Development.

Neighbors and even a councilman had failed to realize a stench wafting in the area around Sowell's home was human flesh.

And there is another suspicion echoing among Cleveland residents, particularly in the black community: that the lives of poor black women aren't worth much, certainly less than had they been suburban white women.

"We're saying you don't have the right to judge whether or not a case is worth being investigated," said Dave Patterson, a local activist who is pushing the legislature to reform the way police handle missing-persons cases, to give more priority to cases involving adults.

Almost a year after the discovery of the bodies, it is still hard to say why the disappearance of 11 women went largely unnoticed for nearly two years.

The reasons are complex, as were the roller-coaster relationships between the women and the family members who knew they were missing and miss them now.

"I had seen her high, missing, trying to put her life together," Jonathan Carmichael, now 25, said of his mother. "I had seen her on a good streak for a long time and then she'd hit a bad number and fall right back onto the streets."

There was no reason to think this time was any different.

The fixed truck door

On the morning of Monday, November 10, 2008, Tonia Carmichael asked her mother for $20 to fix the door of her truck.

Barbara Carmichael, now 72, knew better than to give her daughter the money. Over the past 10 years, she'd ceded plenty of loans to Tonia and even watched her steal her own car. But a mother never turns on her daughter, no matter how many mistakes she makes, says Barbara, whose strength seems to burst from her delicate, 5-foot frame.

"Tonia was like a train wreck you see happening, and you can't stop it," Barbara says. "I really thought if I cared enough and tried hard enough, I could change her and make a difference in her life."

Barbara was raised by a single father in Cleveland in the 1940s and yearned for a daughter for as long as she can remember. Two factors fueled this longing: Growing up in a house full of brothers and her own mother's mysterious disappearance during a cross-country vacation when Barbara was 2.

So Tonia had been an answer to her dream.

Barbara was just 17 when her baby girl arrived, on June 30, 1956. Single and working as a nurse, Barbara would remove the ribbons from bouquets in the hospital and tie them in Tonia's hair.

Barbara had already lost a son, Donnie, 21, a victim in an armed robbery in 1976. So despite her best judgment, Barbara couldn't refuse Tonia's request. She gave her the $20.

When nighttime came and there was still no word from her daughter, Barbara knew something was wrong. She called her grandchildren for help. Together, the whole family canvassed nearby neighborhoods in the dark.

A few days later, driving in the rain in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood, Barbara spotted Tonia's truck on the corner of 118th and Kinsman Road.

It was four blocks from Sowell's home, and the door had been fixed.

"Twisting it, twisting it, twisting it"

A month after Barbara reported her daughter missing to police, a 40-year-old Cleveland woman, a deep gash on her right thumb and scratches on her neck, frantically approached a patrol car in the Mount Pleasant area, according to police records.

She told officers a man in a gray hoodie offered her beer, and when she declined, she said, he punched her in the face several times, tried to rape her and dragged her toward a house at 123rd Street and Imperial Avenue.

"He just kind of twisted my neck, twisting it, twisting it, twisting it," Gladys Wade, who managed to escape from the man, told CNN last year. "I was gouging his face at the same time. At the same time, I was trying to take his eyeballs out. It was like the devil, you know? Eyes glowing."

The man, who Wade said was known as "Tone," was in fact Anthony Sowell, police reports show. Sowell told police a different story. He claimed Wade, who had a record for forgery and assault, had robbed and assaulted him, according to the Cleveland Plain Dealer newspaper.

Sowell, who had spent 15 years in prison for attempted rape, had grown up in East Cleveland, a suburb of Cleveland. He had joined the Marines at 18, an opportunity that took him to California, North Carolina and Japan, according to authorities. He served eight years, then returned to East Cleveland. People who interacted with him after his release said he appeared to be "a normal guy," known around the neighborhood for selling scrap metal.

A young father who lives on Imperial Avenue near Sowell remembered shooting dice with him on several occasions. He said Sowell had let him hide drugs in his backyard, where eventually police would find five of the 11 bodies.

Elias Tayeh, a graying man in his mid-50s who owns a convenience store across the street from Sowell's home, recalled talking to him at the cash register two or three times a week. He noticed Sowell, who often "stunk," would purchase Cobra malt liquor and an abnormally large number of trash bags.

On December 8, 2008, when police went to Sowell's house after Wade's complaint, they knew he was a sex offender, according to an e-mail from Nancy Dominik, a spokeswoman for the Cleveland Police Department.

He was in the Tier 3 category, the most dangerous classification in Ohio, the Cuyahoga County Sheriff's Office said. Officers had checked on him numerous times at his home. During those visits, the officers didn't notice a smell or anything unusual, said spokesman John O'Brien. He also pointed out that officers weren't allowed to enter the home during the checkups.

But a police report from the December 8 visit shows authorities saw blood droplets on the walls and steps.

In a second report written two days later, a Cleveland officer said they did not see any "visible signs" of Wade being punched in the face. The officers told CNN affiliate WKYC that they dropped the case after Wade declined to press charges.

After Wade's complaint to police, six more women would disappear.

Police defend investigation

Ed Tomba is a decorated officer with short gray hair and a serious face. He's worked 20 years with the Cleveland Police Department, first as a homicide detective before moving up the ranks to become deputy chief.

He's heard the criticisms about his team's performance:

Why wasn't Wade's complaint investigated more thoroughly?

Why weren't missing-persons complaints followed up on more rigorously?

"I think we've done a very good job," Tomba said. "We have a solid protocol."

Tomba declined to comment specifically about the case because it has not gone to trial.

The police have pointed out that only four of the 11 families reported their loved ones missing. The department has also said it is currently reviewing its missing-persons practices.

The Cleveland police received 1,576 missing-person reports last year, and as in most cities, missing children cases receive top priority.

The cases of missing adults present a different challenge because adults can legally leave home without telling anyone. Cleveland police say most missing adults return within a month. Unless foul play is suspected, detectives rely on families to come forward with new leads.

Often, officers say, families fear prosecution and don't come forward when a missing loved one has been involved in criminal activities.

Of the four families that filed reports in the house of horrors case, Michelle Mason's was the most insistent. Mason's missing-person report is 34 pages long, chronicling several leads and search efforts.

Mason's mother, Adlean Atterberry, 67, trekked though Mount Pleasant and the east side of Cleveland putting up fliers about her daughter. During rush hour, her family waved posters with Mason's picture on it on street corners.

They say fliers near Sowell's house were mysteriously removed.

"You don't know what outcome is going to make you happy after searching so long for the person," says Frankie Williams, Mason's 24-year-old son. "You don't know if you even find them alive if it will make you happy or angry that they were alive and didn't say anything."

Among the families that didn't file a missing-person report was that of Amelda Hunter.

Her son, Bobby Dancey, recalls his mother whipping up pepperoni pizzas from scratch. They used to laugh and joke at the dinner table together. She taught him to dance in their living room, four houses away from where Sowell lived.

But she also abandoned her son countless times to use drugs. So when she disappeared in the summer of 2009, Dancey never filed a police report.

"She had left before," he said quietly.

Targets of serial killers

Serial killers prefer to target individuals engaging in unaccepted behaviors because they can use the victim's lifestyle as leverage in their efforts to control them, says James McNamara, an FBI expert on serial killings.

The victims' "invisibility" enables the serial killer to work without notice, several experts on serial killers say.

It took more than two decades for police in Los Angeles, California, to crack the case of the "grim sleeper," who terrorized and killed at least 10 black women, some working as prostitutes. In July, Lonnie David Franklin Jr., 57, was arrested and charged with 10 counts of murder. Franklin has pleaded not guilty and is awaiting trial.

In North Carolina in 2003, police began discovering the remains of women, almost all black prostitutes, around the small town of Rocky Mount. Nine bodies were found.

Many of the victims led dangerous lives, according to local media reports, slipping in and out of random cars and coming into constant contact with strangers.

One man has been charged with one murder. Authorities are still investigating the other deaths.

After analyzing more than 110 serial murders, Steven Egger, an associate professor of criminology at the University of Houston at Clear Lake in Texas, found at least 75 involved victims who were drug abusers, homeless or prostitutes.

--Jack Levin, professor of sociology at Northeastern

"People are quoted on television saying they deserve it because of their lifestyle, forgetting about the fact that it's somebody's daughter, wife, possibly somebody's mother," Egger said.

There is no simple method of categorizing serial killers. Many people believe serial killers are reclusive misfits or white males, but that is not true, according to the FBI. Authorities have caught serial killers who are black, Asian and Hispanic, but they say white serial killers usually receive the most media attention.

Serial killers usually blend into their surroundings. A combination of biology and environment influences someone to become a serial killer, the FBI says. Serial killers prefer to constrain their killings to one area because they may feel comfortable there.

Their motives also vary. Some are sexually motivated while others are obsessed with the power they experience when they kill.

"These killers know what they are doing is wrong, but they simply don't care," said Jack Levin, professor of sociology at Northeastern University.

"They choose to do it because it makes them feel good."

Finally, the horror is uncovered

The bodies at Sowell's home were finally discovered when a 36-year-old Cleveland woman went to police.

On September 23, 2009, she reported that Sowell had invited her into his home for beer. Her description of what happened there was eerily similar to the events laid out by Sowell's 1989 victim and, later, by Gladys Wade.

The woman said Sowell punched her in the face and began performing oral sex on her. She was able to escape, she said, by promising to return the next day.

Officers issued a warrant for Sowell's arrest based on her account.

They entered his home on October 29, 2009. First, they discovered two bodies rotting in the attic, then five more more buried in the backyard. Eventually the body count reached 11.

Barbara Carmichael gave DNA samples to the coroner's office a few days after learning about the bodies in Sowell's yard. But Barbara already knew what the results would show. It was a mother's intuition.

She is trying to move forward, but her home is a constant reminder of Tonia.

The shiny blue beads that dangle from her curtains in the kitchen? "Tonia picked them out," Barbara says.

The shoe holder in her living room? "We built it together," she said.

Police continue to investigate Sowell. Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Bill Mason is reopening 75 cold cases. In East Cleveland, the suburb where Sowell lived in the 1980s, police are looking into three murders that involved strangulations and one missing person. They believe Sowell may be connected.

In February, a woman testifying before Judge Timothy McGinty of the Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court in an unrelated matter said that Sowell attacked her. (CNN does not name victims of sexual assault unless they consent.) And another woman, who according to a police report came forward after the bodies of the 11 were found, told police she survived an attack from Sowell.

She also quoted him as saying: "You're just another crack bitch from the street. No one will know if you are missing!"

'You only get one mom'

Donnita Carmichael, 33, is angry at her mother for choosing drugs over her and her brother.

But some days she blames herself, thinking she should have been more supportive. Before her mother's disappearance, Donnita spent seven years working in a drug rehab clinic, talking her clients through their most complicated troubles. But when drugs haunted her own family, she fumbled for words.

That's a regret Donnita will carry for the rest of her life.

"You only get one mom," she said. "I would take her any day using drugs rather than her not being here."

--Donnita Carmichael, daughter of Tonia Carmichael

In March, Donnita and her brother Jonathan, now 25, attended a gathering for victims' family members. Seven other members of Tonia's family were there, including her great-grandson, whom she never met.

Marcia McCoy, a Cleveland resident who organized that event and others, says she wants it known that the city won't forget the Imperial 11. She handed out gifts to their families: purple sweat shirts with the words "Invisible No More."

Taking to the microphone that night was one of the women's children, a fourth-grader named Nira. She is the daughter of Le'Shanda Long, who at 25 was the youngest victim.

Wearing her hair in braids just the way her mother liked, Nira confidently recited a poem about strength and shared fond memories of her mother reading stories to her and tucking her into bed.

She is among the 23 children, at least 36 grandchildren and one great-grandchild the Imperial 11 left behind.

Nira has no idea how her mother died, and no clue about her troubled history.

All she knows it that her mother is gone. And she will never get to know her.