What Syrians want you to know

55 stories of lost homes, lost lives — and hope after five years of war Click or tap a photo to read more

Mouneer Bu Kolthoum

Amman, Jordan

Hip hop musician

Mouneer, 24, was a student in Damascus before the war; now he’s a hip hop musician in Amman. He never thought the war would go on like this, he says. “But I am proud as hell to be Syrian and I wouldn’t change anything about that.”

"A lot of people try to categorize Syrians — he’s regime, he’s this or that – I’m always just a musician. I wasn’t looking for this, but I found myself in a position where I could speak for a lot of Syrians (and displaced Palestinians) through my music. About loneliness, about no rights … about being forced to live away from the places they want to live.”

He hasn’t seen his family and friends for three years. “Now everyone around me seems like they are on another planet with totally different thought patterns,” he says.

When the war ends, the first person he wants to see is his girlfriend, who he also hasn’t seen in three years. “I want to be living in a place where I can work, have my civil rights and pay my rent.”

Omar

Antakya, Turkey

Omar’s young life has been one of constant movement. His family first fled Aleppo for Cairo, and then in 2013 to Antakya, Turkey in search of work. Next month Omar will relocate to Norway, joining his father who has gained residency there.

Asked what he thought of moving to Norway, the four-year-old said, “I like to travel.” Every time he moves, he puts all his things in a small backpack that he carries himself.

Because Omar has moved so much in the past five years, he’s had to learn new languages so people can understand him – and he’s become very good at making new friends, he says.

When the war ends he wants to see his bike again – and when he grows up he wants to be a football player and own a phone so he can talk to his family in Syria.

Hanine

Baalbeck, Lebanon

Baker

Hanine, 17, has grown up during the war. She was in middle school in Damascus when it started. Now she works in a pastry shop in Baalbeck, Lebanon.

“I became stronger,” she says. “I feel that I lost my femininity. I’m not the girl who takes care of how she looks, or puts on make-up anymore. I don’t think about things like this at all now. I forgot Hanine, the girl. I have become more practical. I am Hanine the laborer now.”

Today, Hanine is the sole breadwinner in her family. “Two years ago I developed into someone I am proud of, because I am capable of juggling all of these responsibilities. I am proud of myself because I don’t think there is a girl my age who is able to earn a living for her family, study, and take care of the house’s chores all at the same time -- not to mention working on developing my talents like singing, painting, acting and handcrafting. I do a lot.”

She doesn’t plan on staying in Lebanon for long. “In five years, I won’t be here,” she says. “I will be in Europe. I hope that I’ll be either a college student studying engineering, or graduated by then.”

“All the people that I loved in Syria are now somewhere else; they are either dead or refugees around the world,” Hanine says. But she does plan to visit Syria again some day.

“I would want to visit places in Syria where I have memories. I miss my friends. I have a friend, Rania El Kaissy, that I love very much. I’ll tell Rania that I miss her so very much, and that I miss our walks together and that I miss spending time with her.”

Nour

Chebaa, Lebanon

Nour, 8, fled Syria two years ago with her mother and brother, making it safely to the south of Lebanon after walking across Mount Hermon for two days.

Her father is still in Syria, but she and her family have lost contact with him. The winter is harsh in Lebanon, and Nour has to help her mother carry blankets they received to help them get through the winter months.

“I want to go back to see my father and I want to go to school,” she says.

Samar and Mohammed

Syria

Samar, 50, has learned how difficult it is to survive in war. She lives with her husband Mohammed, 57, in a garage in Syria. Samar says it is better than living in a besieged area.

“We had to make bread by ourselves, like the old days. We are tired now more than any time before.”

Neither one can remember a good memory from the past five years. Samar, breaking down as she speaks, says she can’t wait to visit her children. “I will hug them strongly. May God bless them.”

Farah Shretah

Netherlands

Farah, 27, is a freelance filmmaker and actress from Latakia. She’s in the Netherlands waiting for permission to be reunited with her daughter.

In the past five years she says she’s had to start over from nothing more than once – experiences that have made her believe in her ability to succeed.

Farah says the biggest change since the war began was the birth of her daughter, who is now three. She lost her own mother when she was a year old – but she’s determined to do anything to provide for her daughter.

If she could return to a war-free Syria, Farah says she would visit her grandmother to tell her the impact she had on her life. Farah says she hopes that her grandmother can wait for her to return, because if she were to pass away, there would be nothing left for her to return to, other than the remnants of old memories and the skeletons of her friends.

Five years from now, Farah dreams of visiting Disneyland with her daughter. She sees them playing together, having fun, feeling safe and being happy. She also sees herself working on a film career and a successful life.

Hala

Gaziantep, Turkey

English teacher

Hala, 27, was about to embark on an English literature university course when she left Aleppo three years ago for Gaziantep.

“I’m in a situation now where the future is unclear, I feel unstable sometimes,” she says. “I am lucky as all my family is now in Turkey, but people in Syria are suffering. During my whole life in Syria, no one told me that you shouldn’t love your country so much because you might have to leave it without saying goodbye.”

She’s grown up in the past five years. “I’ve learned that I can be independent and can do anything I want, and that I have many strengths. I know that women can do anything. I know what rights we all have and what challenges and situations I can endure – and I know what I can do to help.”

Hala says she’s still trying to help out Syrians, even though she’s not there. She’s started a Master's degree in Gaziantep, and is “trying to be as hopeful, funny and happy as much as I can.”

She hopes to return to Syria one day. “I want to visit my grandmother’s grave. I want to visit my neighborhood, my school, my university. I miss the Syrian people, not just one person – one person is not enough,” she says.

“I imagine myself walking with children, rebuilding what is being destroyed right now, helping people with their needs. Maybe I will be teaching English, as that is what I can do – helping my country to be strong again.”

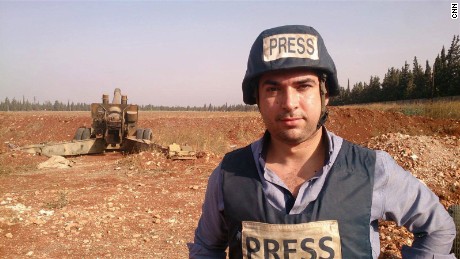

Emad Najm Husso

Innsbruck, Austria

Journalist

Emad, 29 is from Aleppo but now lives in Austria. He works as a journalist and as a coordinator in the Life Makers Team, a civil work organization active in Aleppo.

“Over the past five years, I unleashed my writing talent,” he says. “The opportunity presented itself as there was a need to report what was happening in Aleppo during the war.

“I was able to work as a journalist -- without the boundaries imposed by the Syrian regime, [without] oppressing freedom of speech and expression,” he says.

In the past year he’s written for a number of media outlets, including Good Morning Syria, while working for a number of aid organizations operating in Syria. But he says he hasn’t reached the peak of his abilities yet.

Emad says he’s awaiting a reunion with his family in Turkey once he secures a residency permit. The wait, he says, “has taught me firmness, determination, and dynamism at both personal and professional levels.”

When the war ends he says he’ll visit his friend Safwan Bakir in Aleppo: “When we meet, I will hug him and say, ‘You see? The war is over and the dream of revolution became true, establishing grounds for a state of justice, freedom, and dignity. I’ve missed you, Safwan.’”

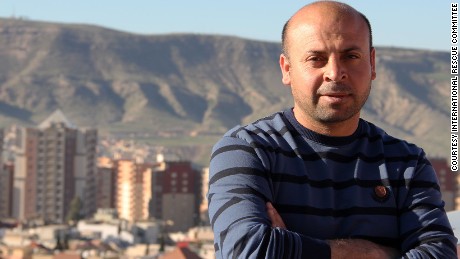

Murad

Mafraq, Jordan

Health volunteer

Murad, 28, was a nurse in Syria before the war.

Before the war he says there was never a day he did not feel like a strong person.

Now he's a health volunteer for the International Rescue Committee in Jordan, and says he has learned something new every day since the start of the war. “The war, leaving my country, life now, the problems – they all teach you how to deal with difficulties, adapt and get on with different people.”

He adds, “In the past five years, I’ve seen and experienced things that made me feel scared. Having survived them though, I feel like I’m not so weak after all.”

Ahmad

Baalbeck, Lebanon

Aspiring singer

Ahmad, 17, was a student in Yarmouk camp before he left Syria. Now he paints houses for a living in Lebanon.

“I was young five years ago, living a normal life,” he says. “I did not know what hardship means, I did not know what life is like.”

“But I have learned so much during these past 5 years; mainly I learned to depend on myself. When I was in Syria, for instance, my parents would earn money and take care of me and my needs. Now I earn a living and pay for myself. I have to work and earn a living, or else we won’t survive as a family.”

Ahmad says he’s at his best when he’s singing. “I sing in front of colleagues,” he says, “but I would love to see myself singing on stage.” He wants to become a professional singer five years from now.

If he could go back to Syria, the first person he would visit is his uncle. “I grew up with my uncle. He was very supportive and I love him very much. He was the one who told me that my voice has potential when I was a child, but I never really believed him,” Ahmad says.

“He used to tell me that he will teach me how to sing, and for two years he tried to teach me little by little, but I wasn’t taking it seriously, and I didn’t have the courage to believe in myself. During these past five years, I discovered that I have a lot of strength in me to overcome all of this hardship. And somehow I became courageous enough to let it all out and embrace my talent to sing.”

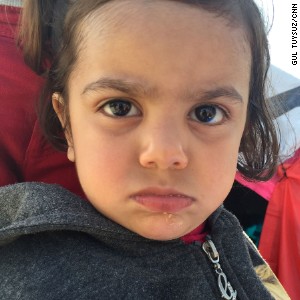

Lamees Taweel

Karak, Jordan

Lamees is 3 and likes to pose for selfies. Her parents are unable to find work in Karak, Jordan and the family is reliant on her older brother Ziad, a waiter, to meet the family’s basic needs.

Growing up in war has meant that Lamees has lived a very different life to that of her older two siblings. In Damascus their lives were filled with constant socializing with friends and family. Her father owned a popular restaurant and this was often the center of social activity. Living in a foreign town where they do not feel safe has meant Lamees lives a very confined life.

At a child-friendly center in town, Lamees has learned that she is a “good drawer” and very good at making friends,. She wants to go to the center every day to meet new friends.

Most nights Lamees helps her father prepare dinner. She’s good at chopping vegetables and would like to have her own restaurant when she is older. And when the war ends, Lamees wants to meet her cousins in Syria.

Niveen

Amman, Jordan

Law student

Niveen, 21, is a university student in Amman. When she arrived in Jordan from Damascus, she made new friends and hoped she wouldn't be staying long.

She has since learned to be patient the last five years in these difficult years. When the war ends, Niveen wants to see her friends and let them know how much she has missed them.

Nirous Hussein

Athens, Greece

Nirous, 8, wants to be a teacher some day. Her family arrived in Greece in late February following a month-long journey from northern Syria. They hope to make their way to Germany.

"If I can go back, I would want to see my cousin," Nirous says. But her mother says that after they left Syria, her cousin died when bombs destroyed their house.

Jood Mahbani

Syria

Journalist

Jood, 29, is a journalist from Homs who still lives in Syria.

“Over the past five years, I realized the value of my life and that of others, and I learned that we should all strive to preserve it. Man can only feel human when free and unchained,” she says.

“I felt at my best when I became involved in community work, meeting new people and visiting new places,” she says. “Another great moment was when my first article was published on a renowned website and quoted by over 15 others. The best part about this is the happiness that I see in my mother’s eyes when she reads my articles, and my friends’ support. These are moments and feelings that I would not trade for the world.”

“When the war comes to an end, I hope I can visit the grave of the first person who encouraged me to write. He gave me support and motivation. I want to apologize to him and thank him, because despite our differences, I can never forget such a dear person who influenced my life so much and that of many others.”

Bushra

Tripoli, Lebanon

Student

Bushra, 7, is the sole survivor of a bomb blast that destroyed her home in Homs and killed her immediate family.

She travelled by car and by foot with her elderly grandmother to Lebanon in 2012, where she has settled in a Danish Refugee Council Collective Center in Tripoli. She doesn’t like to talk a lot, and is never without her stuffed toy “rabbit” she managed to bring with her from Syria. It is the only possession she has from home.

Bushra doesn’t like to go outside – the only time she leaves her apartment building is when she travels to and from school with her best friend Mahmoud.

She feels strongest when she’s learning at school, where she forgets to be sad. She doesn’t know who she would visit after the war, because her family is gone. But when she gets older she wants to return to Syria to be a French teacher.

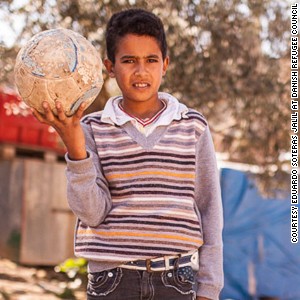

Chindar Farhan el Kurdi

Amman, Jordan

Chindar, 13, is from Amuda and is the eldest son in his family. He’s illiterate like his parents, and doesn’t go to school in Amman because he doesn’t like how he’s treated by the teacher and other pupils.

In the past five years he says he’s learned a lot about being quiet. His family of five lives on $10 per person per month, which they receive from World Food Program. Everything they eat and need must be subtracted from this sum.

He said he would like his family to have their own house again: “The tent is not so comfortable … when the rain comes, the water gets inside.” “My life was better in Syria,” he says. “I did things. I went to school. I miss my home and my relatives – we were so close to each other.”

Chindar says he’s at his best when he plays football. But he doesn’t own his own ball and has to wait to play with other children. The only objects he owns just for himself are marbles -- he has a jar full of them because he is a good player and always wins.

When the war ends he wants to visit his grandmother back in Syria. And he wants to become a blacksmith.

Raheem

Akkar, Lebanon

Student

Raheem, 11, fled Idlib for a settlement in Akkar, Lebanon. He wishes he could be alone more, he says. “In the camp everyone is everywhere all the time.”

Raheem doesn’t like to complain, but sharing a cramped shelter with nine other family members is hard.

He says: “In Syria I had my bike. I’d ride with my friends every day, to school and around. There were many fields to play in, but here there is nowhere, just roads and traffic. If I had my bike I would ride to the ocean. I can see the ocean -- but I have never been there.”

Every day, he tries to help his mother look after his younger siblings. He tries to do everything for himself so he is not a problem for his mother. He takes himself to school and makes sure he his homework every day.

In the future he wants to be a lawyer so he can help people know their rights – especially refugees.

Taqiya Osman

Idomeni, Greece

Taqiya, 50, is a housewife from Al-Bab who is now in Idomeni, Greece, one of hundreds of thousands of Syrians seeking refuge in Europe.

In the past five years she says she’s learned that God is protecting her and her two youngest children who she’s travelling with.

“The rockets, the bombs, they fell all around us, but we were spared. One was next to our house, but it didn’t explode. Three weeks after we left I was told that a bomb destroyed our house.” In five years from now she wants to be back in Syria – and to have gone to the Hajj.

The first people she wants to see when she heads home are her four older daughters, who are all married and still living in Syria. “What can I say? I kissed the ground when I made it to Greece with my two other children. But all I want to do is kiss the ground when I get back home to Syria.”

“I am afraid of being a foreigner in a strange and large land. I am afraid my daughters will get lost, but I was more afraid of the airstrikes.”

Ahmad Bayer

Amman, Jordan

Teacher

Ahmad, 30, used to be a student in Daraa, but now he’s a teacher who co-directs a children’s cultural project in Amman. He says he is extremely proud of his rich Syrian heritage, and it would be a tragedy if today’s children did not share this view.

“I believe for anyone to feel a sense a belonging to where they are, they must respect it. This work is my commitment to my people,” he says.

He says his ability to take opportunities and integrate into Jordan stems from his strong sense of knowing who he is.

It’s a trait he says comes from his maternal grandmother, who raised him to be proud of his culture. “We don’t have anything that splits us as humans. It’s just up here,” he says, tapping his head.

Ahmad says the past five years has made him unable to trust strangers – but he’s working on his relationships.

Obayda Ghassib

Stuttgart, Germany

Physician

Obayda, 25, is a doctor who spent six months during the war working in field hospitals on the Turkish-Syrian border.

From there, he decided to take the boat and land journey from Turkey to Greece and across the Balkans before making it to Germany.

The last five years have changed Obyada because he has had to learn to become self-sufficient since his parents are refugees in Lebanon. Since arriving in Germany, Obayda says he feels human again. In five years he hopes to be practicing medicine in Germany.

Refaat Mahassen

Amsterdam

Refaat, 31, worked in human resources in Syria before he ended up in Amsterdam.

The past five years have taught Refaat that life is fragile and challenging. He approaches life differently now, he says, doesn’t take things for granted, and tries to enjoy what little he has.

Once the war ends, Refaat would like to see his parents, family, friends and other loved ones – but he’s not sure that will be possible. He fears that Syrian society has been completely shattered by death and migration – and that if he returned, there’s a chance no one would be left.

Five years from now, he sees himself where he is now, in the Netherlands, surrounded by family, loved ones and friends old and new. He hopes to have started a new career by then, but most of all he hopes that he’ll be happy.

Alma Saleh

As-Swayda’ and Damascus, Syria

Teacher, reporter

Alma, 30, lives in as-Swayda’ and Damascus. She was a student when the war started, but now she’s a Spanish teacher and a reporter who volunteers with children.

“My entire life changed during the war,” she says. “I learned to stay strong and see things differently. I discovered how strong-willed and stubborn I am, and realized that I am capable of finding alternatives to continue my work in spite of the harsh circumstances.” “I feel at my best whenever I finish what I have to do regardless of everything, like when a psychological support activity is successful and I leave a good impact on the child, or when I write an article about life in as-Swayda’ and it gets published despite the risks.”

“After the war, I plan to visit Daraa and see the parents of a friend of mine. I want to apologize to his father for not being able to help him during the war. This apology goes to all of the residents of Daraa as well.”

“Five years from now, I hope to achieve one of two dreams of mine: I want to start a radio station in as-Swayda’ to echo the voices of its people, or establish a school for the displaced people arriving in the city and for orphans, including basic school materials and psychological support.”

Basel al-Malla

Latakia, Syria

Journalist

Basel, 23, lives in his hometown in Latakia governate. He used to be a student and volunteer, but now he works in media.

“Over the past few years, I learned to rely on myself more than ever, and I tried not to grow attached to anyone around me, for I could lose them in any moment, either because of their traveling or the security situation,” he says.

“The war in Syria has had an impact on each and every one in the country. The governorate that I live in is relatively stable, but that is not enough for me to feel safe. I always feel like I need to work harder because I will leave Syria one day.”

As the cost of living rises in Syria, Basel has taken on other jobs, including photography. “I often grow tired of the workload and want to quit, but then I think of my family and quitting is no longer an option,” he says.

“Unlike most people, I do not plan to visit anyone when the war ends – or at least I have not thought about it. I would rather have my friends who left Syria return home so we can see each other here.”

“As a child, I used to see all the beautiful regions of Syria on television, and I dreamed of visiting them when I was old enough. However, it is too late now, for the war has destroyed everything that is beautiful in this country.”

Walid

Zaatari refugee camp, Jordan

Walid, 29, is from Daraa. Today he lives in Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan.

The war has changed him mentally and physically. “At the beginning of the revolution, the very early days, I participated in demonstrations and I used to attend university at the same time, wishing to finish my education,” he says. “I used to also visit my friends in Damascus, where I always had the most joyful time, but then things became very difficult and I had to drop out of university and I was not able to contact my friends like I used to.”

“I have lost a limb, which is my leg,” he says. “And in terms of the psychological aspect, I now have new feelings of hate, contempt and revenge. My viewpoint regarding people around me has changed. I discovered that no one can benefit and help the other, even countries and nations cannot did not help us in anything, whether Arab or foreign countries.”

Walid misses his family -- “each member of it, no exceptions: my father, mother, my wife, my siblings,” he says. “I would like to tell them that life without them is meaningless, and that the most tragic thing that happened to me was not my injury, it is the fact that I am distant from them. I am willing and ready to accept the loss of all my limbs if that would make me see them in return.”

Marwan

Mafraq, Jordan

Health volunteer

Marwan, 29, is from Damascus but now works as a health volunteer in Iraq for the International Rescue Committee.

“I had bigger dreams than this,” he says. “My goal was to continue my education. I wanted my parents to see me graduate, but I had to leave Syria. When I was in Syria I had opportunities, now they are limited. I’m very proud of being a volunteer, but I feel like I could do so much more.

“The young generation of Syrians have lost so much – their childhoods, their education, health, safety and care. I want to return to my country and help build it again once the war is over. I want to spread peace, love and justice and unite the people of Syria once more. I want us to take care of this young generation and raise them to make up for everything they lost and everything we lost.”

Rakan

Al Sarhan, Jordan

Rakan, 23, left his hometown of Homs and is now a refugee in Jordan. He can’t wait to go home.

“I don’t think a day has passed in the last five years where I’ve felt like the best version of myself. I feel weak and humiliated. As a refugee, some people give you respect; others don’t. It’s very hard adapting to the situation here. Life in Syria was very good; I had my freedom, I could come and go as I please. Here in Jordan, I feel constrained.”

“The most important thing for me is to return to my homeland. Even though there’s no one left – everyone I know there died. Even if I have to live in a tent, I just want to go back to my country, nothing else matters to me.”

Haidar Razzouq

Homs, Syria

Radio correspondent

Haidar, 34, is a radio journalist in Homs. Before the war, he says, he had a normal life and “wanted to be a good Syrian."

As a journalist covering five years of war he says he was a “little naïve and immature” before the war started.

In the next five years, he would like for the war to end and Syria to return as it was before the conflict.

Radwan

Gaziantep, Turkey

Mercy Corps

Radwan, 25, worked at a telecommunications company in Aleppo when the uprising began, and he was studying law. “Everything stopped and I was unable to obtain my law school certificate,” he says. “I was very sad.”

Today, he works for Mercy Corps in Gaziantep. “During the last 5 years, we, as Syrians, have been faced with circumstances that have changed us as a society and as individuals,” he says. “We’ve lost so many people that we know. I am amazed that we are still able to live our lives, without surrendering to these challenges, without giving up.”

“I’m happy to be part of this humanitarian work that is trying to reach the Syrian community … I know my contribution may not be as dangerous as for the people who are working under shelling every day -- but at the same time, it is better than not doing anything.”

When the war ends, there are two people Radwan wants to visit. “I want to see my sister, I haven’t seen her since I left Aleppo almost two years ago. She is suffering a lot with her family and two daughters. It is really hard that I haven’t been able to see her – they have no electricity, no internet, we cannot even communicate.”

“I lost a friend of mine, he was working in the civil defense, helping people during airstrikes and shelling. I want to go to his family and give them my condolences and put a flower on his grave.”

Radwan wants to return to Syria, but says “the solution needs to come from those who are managing the politics -- they have to take the decision to end the war and bring peace to Syria.”

“In five years’ time, I see myself teaching and helping people recovering from trauma. Following this war we will have an uneducated generation for a while. This is a serious issue for our country and communities, and I want to help.”

Muheeildin

Gaziantep, Turkey

Mercy Corps

Muheeildin, 40, was a lawyer in Aleppo before the war – but when ISIS came to his village, he fled to Gaziantep with his family.

“Everything has changed” in the past five years, he says. “My career, my friends, my lifestyle, my country, my language.”

“I possess a strong will to face difficulties and cope. Whether it is leaving my home and coming to a new country with my wife and children, and leaving all of my relatives and friends behind, or learning a new language – Turkish – to get by.”

He says he’s been the best version of himself in the past three years, working to help others in need: “My best moment was probably when I was in the field, inside Syria with Mercy Corps, meeting those in need face to face and being lucky enough to be in a position to help them.”

Muheeildin hopes to return to Syria when the war ends. “The first person I want to visit when the war ends is my best friend, he was killed by a sniper in Aleppo,” he says. “I want to visit his grave in Aleppo.”

Mohammad

Sidon, Lebanon

Vegetable seller

Mohammad, 17, is from Homs. Today he works at a vegetable market in Sidon, South Lebanon.

“When I was in Syria, I didn’t worry about anything,” he says. “I didn’t have to worry about anything but my studies. I wasn’t working. My day would be going to school, doing my homework, and playing with my friends. When I first got to Lebanon, I felt the change. I got depressed, and started worrying about things I knew that a boy my age shouldn’t worry about. Sometimes I would sit by myself, remember my friends in Syria and just cry.

“Then I met some people here in Lebanon and I made a great friend, Wassim. We know everything about each other. This friendship between us made me feel a bit better. I am not as depressed as I was before.”

“I have been in tremendous pressure regarding my legal papers in Lebanon. There is no way for me to extend my papers unless I go back to Syria; but that is too dangerous. So now, I don’t have legal papers and every time I leave my tent I’m risking being captured by the Lebanese police. I am very afraid.”

“I think in general I’ve become much calmer,” Mohammad says. “It’s a good version of me for the people around me I think; but they don’t know that the reason I’m this calm is because I feel broken.”

The first person Mohammad wants to see if he goes back to Syria is his cousin. “She was my best friend,” he says. “We would go to school together, do our homework together and play together. I would tell her that I miss her so very much. The war changed both of us a lot.”

In the future Mohammad wants to be anywhere besides Lebanon. “In five years I hope to have a good job where I’m respected, unlike the job I have here,” he says. “I hope to be living in my house, and own a car. I want to live a normal life outside of Lebanon. Life in Lebanon is terrible.”

Kinda Hamwi

Netherlands

Kinda, 28, is from Damascus and worked in advertising before fleeing to the Netherlands.

Looking back on her life during the war, she’s stunned at how she and her fellow Syrians handled the situation around them. Even though they were surrounded by explosions, shelling, and kidnappings, they simply kept going, day by day, without fear and anxiety, almost totally numb to what was going on.

But there’s only so much loss a person can take, and in 2012 Kinda says she became severely depressed. It was then that she had the epiphany that there must be a reason she was still alive – and she has since grabbed life with both hands.

The first place Kinda wants to visit if she returns to Syria is her father’s grave, since she wasn’t able to attend his funeral in 2013.

In the future Kinda sees two visions. One is a stable life in a foreign country where she can get asylum and be accepted by the community. The other is a future where she returns to Syria to help rebuild her beautiful country.

Ali Mulhem

Gaziantep, Turkey

Ali Mulhem, 28, had just graduated from medical school when he met his fiancé at a demonstration in 2011. He spent the start of the war encouraging people to join the opposition until he was arrested by Syrian security forces.

Released after three months in jail, Ali Mulhem lived at a hospital in the Yarmouk refugee camp treating wounded people until he says he was detained again and tortured.

That’s when he and his fiancé left for Gaziantep, Turkey, months apart.

After five years of war he says he has become a "monk," finding “happiness in the regular and basic things in life such as having food, water and sleep”.

He can't go back to Syria, he says, “but at least the love of my life is with me.”

Shaha Othman

Athens, Greece

Shaha, 20, travelled from Aleppo to Greece in late February, crossing by sea in a boat driven by her father that held about 75 people.

"The children were so scared,” she says. We were all so scared. We left at night and arrived when it was day.”

Her family – all nine children and both parents – survived the trip. They want to go to Germany because there’s more opportunity there. Before they left, Shaha had completed her first year of university to become a primary school teacher. But their house was bombed and they had to flee.

“I miss my friends the most. I miss my life. I miss everything about my home,” she says. “If I could go back I would tell my friends how much I miss them. I love them.”

“In five years I want to be back in Syria."

Selda Hussein

Athens, Greece

Selda, 10, and her family arrived in Greece in late February following a month-long journey from northern Syria. They hope to make their way to Germany.

She says she use to live in a beautiful house but now she’s afraid to sleep. “I wake up when there are planes and I am scared,” she says. If Selda could go back to Syria, she would visit her uncle – the only family member who didn’t make the journey: “I would tell him, ‘I miss you so much.’”

“I don’t remember anything before the war,” she says. “I just remember the bombs.” When Selda grows up she wants to be a doctor so she can help people.

Saleh

Dohuk, Iraq

Social worker

Saleh, 35, says his life in Iraq is completely different to the life he had before. Once a lawyer in Syria, he is now a social worker for the International Rescue Committee.

“I have just won a humanitarian award for my work with IRC. The fact that I was chosen from staff all over the world makes me very happy and proud.”

“I want to return to my homeland. I hope I’ll have a calm life with my family, and I want my children to have a different life from the one I have. Family is the most important thing for me and I will do everything I can to make things easier for them. I would like to apply in Syria the things I have learned in Iraq, to build a better future for our children.”

“Once the war ends I would like to visit my parents, who remained behind in our village when we fled. I would not say anything, I would only hug them.”

Mahabad

Dohuk, Iraq

Child protection officer

Mahabad, 25, was a philosophy major at university before she became a refugee in Iraq. Now, she works as a Child Protection Officer with the International Rescue Committee.

“In the past five years, I have realized how strong I am. I have found inside myself a powerful ability to cope with the difficulties I encounter,” she says. In August 2014, thousands of Syrian refugees crossed the border into Iraq. "As a refugee, I saw myself in them, and I worked day and night to provide them with the support they needed, especially the children. Their smiles were the best reward for me.”

“Having to leave university has been hard for me, so I hope in five years time I will have been able to return and complete my studies. I would like to meet my dearest friend from university. I don’t know what I would say to her at first; maybe I wouldn’t be able to say anything at all as I would just be so happy to see her.”

Manal AbdulRahman

Idomeni, Greece

Manal, 47, was a paralegal in Damascus but is now in Idomeni, Greece, one of hundreds of thousands of Syrians seeking refuge in Europe.

“We never thought that Syria would lose security, it was synonymous with security,” she says. “With the current situation, we learned to live with the bombs, artillery, tanks, lack of water and power, things we took for granted. We learned to survive.”

Manal says their ordeal has made her more irritable. “My husband and I are always arguing, it’s because of the psychological pressure on us all the time. The simplest things can set us off, our nerves are frayed.”

Manal wants to go home to a Syria that is safe. If she returns, she wants to see her parents, “to tell them I love them. They didn’t want me to leave. I want to say I am sorry, I had to leave, what we were faced with overpowered me.”

Ahmed Sheiko

Idomeni, Greece

Ahmed, 29, was a tailor in Aleppo. Now he’s in Idomeni, Greece, one of hundreds of thousands of Syrians seeking refuge in Europe.

Asked what the past five years taught him, he says: “I learned about hatred, betrayal, and struggle. That people are cruel.”

Ahmed says he was never involved in the war or the politics. “I tried to stay away from problems,” he says.

He wants to see his parents if the war ends, but adds: “Who can think that far ahead? Look around us. I just want to be somewhere, anywhere peaceful where we can live.”

Nada Sarraj

Idomeni, Greece

Nada, 28, is from Abu Kamal. Now she’s in Idomeni, Greece, one of hundreds of thousands of Syrians seeking refuge in Europe.

“I lost all hope” in the past five years, she says. “I cry easily.”

In five years she says she hopes to have a home to raise her seven children. “I don’t want a car or gold or anything, a simple life. And I want to work. My education stopped when I was 13 years old. But I want to work as a secretary or a nurse.”

Fatima

Lebanon

Fatima, 64, lives in a tent in Lebanon after fleeing Homs in 2012. Leaving with her son and his family, the family lived near a riverbank just across from Syria until that home was washed away.

She’s helping the family set up in their new settlement, leveling the ground underneath the tent. “I got younger since we left Syria,” she jokes.

A mother of five, Fatima misses her daughters, who are still in Syria. She says, “As soon as I can go back I want to go see them. One of them just gave birth to a baby boy that I still have not laid my eyes on.”

Gulbahar Daoud

Idomeni, Greece

Gulbahar, 1, is from Afrin. Her mother Berivan says she slept the entire boat ride to Greece.

“She’s always sick and crying,” Berivan says. “We want a good life, we just want her to be happy.”

“Ours was a life of suffering. We want her to forget our life -- what do we want with Kurdish or Arabic, what has our homeland given us?”

Nareen

Dohuk, Iraq

Child protection officer

Nareen, 26, has lost a lot in the past five years. “I have lost close family members, lived in poverty, not been able to graduate from college,” she says. “My little sister died in Syria and I have not even had a chance to visit her tomb. I had two choices: either to fall down or stand up. I have found out that I am strong and I never give up.”

Nareen is proud of the work she’s done for the International Rescue Committee in Iraq with vulnerable children. She’s also proud that she can support her family.

In the future she wants to live with her family in the UK. “I hope I can be an active and successful person there,” she says. “I would like to continue to help children wherever I am. I am also interested in going back to college and studying either fashion design, fine arts, or human and child rights.”

Siwan

Dohuk, Iraq

Child protection worker

Siwan, 29, was a teacher in Syria when she had to flee with her husband and baby. Once they made it to Iraq, Siwan decided she wanted to help refugee children and became a social worker for the International Rescue Committee.

“I felt weak, scared and worried [when we fled], but now I feel strong, brave, confident and calm,” she says.

“Seeing the impact of the IRC’s work on children who had experienced war and displacement was very rewarding, and I still remember the happy looks on their faces. Since then I have been dedicating all my energy to working with refugee children.”

“There are so many people I want to visit once the war ends! I miss my sisters and brothers and friends that have remained in Syria, but the first person I want to visit is my dearest childhood friend. I want to hug her and tell her how much I missed her."

“I want to be living in a safe place – I do not mind where, as long as it is safe. I also hope I will be an experienced social worker by then to be able to better help children, including my own.”

Hamze al-Ashmar

Idomeni, Greece

Hamze, 2, is from Yarmouk camp in Damascus. The camp was under siege, and he and his grandmother were both ill.

“There was no medicine,” Hamze’s father says. “He had a high fever. So we took them to the checkpoint, they sometimes let emergency cases through. We made the request and waited for two days. We left and never looked back.”

Hamze doesn’t sleep well, his father says. “He’s always crying and he doesn’t play like before.” His parents dream of being in a place where they can breathe and live – a place they can raise their son.

Louna Al Bondakji

Berlin, Germany

IT student

Five years ago, Louna, 22, lived with her entire extended family in one building in Damascus. Syria.

Life was easy, she says. Now in Berlin, she has discovered she has the strength to live here and live here alone far away from her parents and friends.

“Five years ago I had my own home, I had a car, I was studying and my family and friends were supporting me. I knew how people think in Syria. Everything was just fine.”

Even though the situation now is challenging, Louna says she is the best version of herself right now in Germany. “For the first time I have purpose in my life”, she says, as she is working on developing her coding skills.

Isa Mohammed

Idomeni, Greece

Isa, 25, is from Idlib. As he makes his way to Germany, he is camped out on the Greek side of the Greek-Macedonian border.

“No one will help you,” is the lesson he has learned in the past five years. “Through hardship, pain and the need to survive and find money, I had to take care of myself and keep my family safe. It is that – staying safe – that turned me into a man.”

Isa cannot think of one moment in the past five years that was a good one.

His worst memory is from the battle for Idlib last year. Starving from hunger, before fleeing Syria, he and his family would put stones on their stomachs to press them down to try to forget about the hunger.

Ibrahim Al-Sit

Amman, Jordan

Milk seller

Ibrahim, 27, is from Damascus. He sells milk now, even though he was a web developer back home. Life goes on, he says.

He never thought he’d leave Damascus five years ago, he says – but when his mother visited him in Amman in 2013, he felt human again. When the war ends, Ibrahim wants to visit his father in Syria, to ask for his forgiveness for leaving.

Jomana

Amman, Jordan

House wife

Jomana, 45, is from Damascus. She and her daughter are living in Amman, Jordan, while her husband and son are in Germany.

Most of her time is spent thinking about Syria, she says. “The first days in Jordan were the best because I was hoping to return to Syria. But now the hope is almost gone and sometimes I say there is no hope.”

In five years, Jomana doesn’t know where she will be. Maybe sailing to Europe or Turkey or anywhere else, she says.

Riyad Agha

Amman, Jordan

Baker

Riyad, 39, says the war has taught him to be patient. He owned his own bakery in Homs but now works as a baker in someone else’s shop in Amman.

In five years, he’d like to be back in Homs as soon as possible, back to his old life.

Addallah Hariri

Amman, Jordan

Addallah, 23, wants to go back to his hometown of Daraa, even though the past five years were normal for him in Amman. He says the best times of his life were in Syria.

Mohamad Ghazawi

Amman, Jordan

Student

Mohamad, 15, was a student in al-Muadamiya. Now he helps his brother at his tailor shop when school finishes in Amman.

In the past five years, he has learned to be “kind and respectful,” he says.

“I thought people who used to be kind turned out to be bad,” he says. If he could return to Syria he would “visit my house, visit my memories, then burn it all and leave.”

“We cannot predict life, and we don't see hope or light at the end of the tunnel. We don't see a solution. I can't tell where I will be in 5 years. I might travel, I might stay here in Jordan, or I might die. No one knows.”

Hussam Mohammed

Azraq Refugee Camp, Jordan

Student

Hussam, 16, says he became a man sometime in the last five years.

All he thought of when he was 11 was playing football when he was in Syria. Now in Azraq refugee camp in Jordan, he says everything is important, and he notices everything around him.

At 16, he says he is the best version of himself yet -- and for the first time in a long time, life is stable and he is able to plan his future.

When the war ends Hussam wants to visit his sisters, who are still in Syria, and give them big hugs.

Sakher Al-Mohammed

Cologne, Germany

Journalist and activist

Sakher, 27, was a political science student in Damascus when he joined demonstrations at the start of the war in 2011.

After living through four years of war, he escaped and came to Germany as a refugee.

He can’t remember life before 2011. In the past five years, Sakher says he has become an activist and is “trying to reclaim our civil rights and freedom of expression.”

Khaled Al-Shalabi

Germany

Khaled, 25, ended up in Germany after walking for two months with an injured leg.

At the start of the war, he lived in the Yarmouk refugee camp in Damascus and worked as a barber. An initial supporter of Assad’s regime, he later joined in on the demonstrations. After the camp was besieged by the regime, Khaled says lost his leg during a mortar attack. He dreams of going back to Syria and working as a barber again.

When the war ends, he says he hopes his “family and I are able to eat dinner together at the same table.”

Ibrahim

Beirut, Lebanon

Ibrahim, 2, and his family fled Abu Kamal after ISIS seized the Syrian town in 2014.

His father Abu Ibrahim, 37, says: "I have never imagined for one second that me and my family will end up in a different country as refugees. Just thinking about the idea itself makes me sick.”

Five years ago he used to own a car repair shop – now in Beirut, he works in one. “I used to help people with food and money,” he says. "Look at us now, we are refugees with no future -- not only my family but thousands of other Syrian families with no future. The entire world is watching."

“I have no family left in my hometown,” he says. “But God willing, when I return back, I would kiss the ground, I would smell its earth and its air. I really can't wait for that day to come."

Abu Ibrahim tears up at the thought where he wants to be in five years. "Home ... I want to be home, where else I should be but my own home with my family?" His wife touches his back as he starts to cry.