There is a natural product we grow ourselves which can be used to make clothing, ropes and even building materials – and much of it goes to waste on a daily basis. But perhaps not for long. An emerging wave of designers is harnessing the power of human hair to tap into issues of the circular economy, identity and beauty through provocative objects and installations.

“It’s very lightweight, flexible, oil absorbent, high in tensile strength – and it doesn’t require any extra energy, land or water to grow,” said Dutch designer Sanne Visser via video call. After recently completing a residency at London’s Design Museum to explore recycling human hair, Visser is presenting a new installation for London Design Festival (LDF) this month. Titled “Extended,” it comprises eight mirrors hung on ropes made from hair collected from salons and barbershops in West London.

Visser adopts ropemaking as a technique across her projects with hair, both to emphasize its strength and to use it as sustainably as possible, without the need for other materials. Sorting the collected waste hair by color and length, she sterilizes and washes it, then sends it to a spinner who turns the strands into threads and yarn using a traditional spinning wheel. Visser subsequently feeds the yarn into her own rope machine to make different types of rope, which have been used to create dog leashes, netted bags, shoulder straps, and swings.

When Visser started working with human hair six years ago, the hairdressers she approached to ask for waste cuttings were skeptical. Many said no. As she has built up a body of work, however – and as new initiatives promoting the reuse of waste hair have grown – it has become easier. One of these initiatives is Green Salon Collective (GSC), which works with hairdressers across the UK and Ireland to recycle hair. GSC collaborates with manufacturers or designers (including Visser) to turn hair into new objects and products – from hair booms (cotton or nylon tubes packed with hair cuttings used to stop oil spreading in seas and on beaches) to building materials.

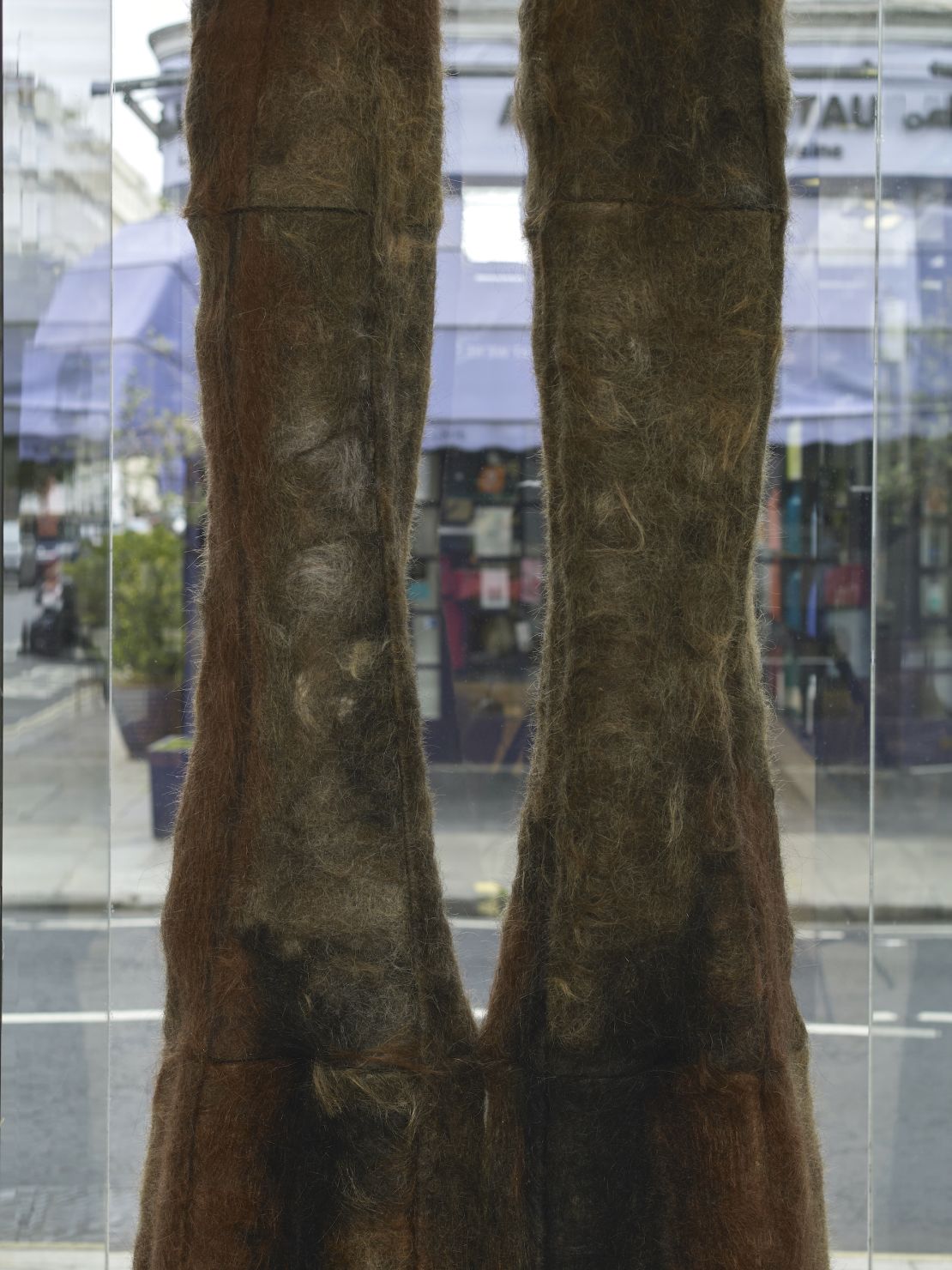

The latter sees GSC working with architecture and design studio Pareid on an installation also at this year’s LDF, comprised of two intertwined, hair-covered columns at a salon in West London. The hair used for the project, titled “Chiaroscuro 1,” is felted and applied as a surface covering.

Pareid is keen to make a fully immersive space using human hair and has been experimenting with using it as a binder for mud bricks. The early prototypes don’t exactly look beautiful, however: “We are drawn to things that might be considered ugly or unappealing at first,” said Pareid co-founder Hadin Charbel in a video call. “Waste like human hair possesses a kind of icky quality – it has that confrontational element to it.”

Confrontation, and challenging perceptions,was are also key to the work of Alix Bizet, a French designer working with hair to address issues of racialized identity, community experience and marginalized beauty. “I discovered, as a Black person, in society there is good hair and bad hair – that’s where the project started. Looking at this discarded material, we can learn so much about society,” she said over video call.

In a 2020 project called “Afro Hair Futurity,” Bizet created crown-like headpieces from afro hair, presented alongside podcasts of interviews with people talking about their personal and professional experiences of afro hair. For earlier projects such as “Exchange” (2016), “Hair Matter(s)” (2016) and “Hair by Hood” (2017), Bizet made garments including hoodies from felted human hair; in workshops with London school students for “Hair by Hood,” the designer prompted discussions about how culture and identity is related to hair, and the role that hair salons play in communities. Other projects have explored the displacing impact of gentrification on afro hairdressers in Peckham, South London, and how to decolonize museum collections through gathering more diverse stories of hair. “My aim is to design for diversity and with diversity, giving visibility and empowerment to all narratives of hair, including afro hair,” said Bizet.

Back at LDF, Anouska Samms – who uses human hair to explore identity on a familial level, as well as interrogate mythology and symbolism – will exhibit some of her striking hair-infused ceramic pieces as part of group show Unfamiliar Forms. These come from her ongoing “Hair Series” (2019-2022), which uses human hair – collected mostly through Instagram callouts – to create sculptural clay vessels and a tapestry, as a way to reflect on maternal relationships. “I was always teased for my hair,” Samms recalled in a video call. “It was just huge, curly and ginger. My mum and grandma are ginger, and I come from a long line of redhead women.”

Samms’ large hanging tapestry, “Big Mother” (2022), weaves locks of red human hair together (some artificially dyed) with cotton and yarn. Through it, Samms hopes to reference a long tradition of weaving that is connected both to women and the idea of birth and creation. Her ceramic vessels, meanwhile, touch on the ancient relationship between pottery and women: in prehistoric societies, women were the primary potters.

Using waste hair isn’t the same as using other waste materials, such as plastic bottles. Hair is both an intimate human material, and a sustainable resource that can be harnessed in practical and creative ways. Although initiatives such as GSC offer the potential to scale up its use, some designers are quick to point out the importance of retaining personal narratives and connections.

“Hair is a living fiber,” said Bizet. “Just because we collect it as a discarded material, it doesn’t mean we’re free to use it without thinking about the ethical aspects. This fast capitalist world of using hair as a new fiber removes the identity of it. Through sanitization, the hair will lose its human aspect and narrative.”

Like Bizet, Visser is keen to connect works that utilize human hair back to the people who donated it. She hopes her “Extended” mirrors will eventually find a home in each of the eight salons and barbershops she collected hair from. There, regular local customers will be able to see the mirrors hanging on the wall and know that, most likely, their hair made it happen.

London Design Festival runs September 17-25, 2022.

Top image: A clay sculpture adorned with ginger hair as part of Samms’ “Hair Series.”