How our planet has changed over time

It can be challenging to visualize the effects of climate change when it happens over time and on such a large scale.

However, NASA has been snapping images of the Earth from space for decades now. With these images compared over time, you can see the toll the warming of the Earth is taking on the planet.

Below are some examples from NASA’s Images of Change project, which shows areas that have been directly affected by the climate crisis.

Neumayer Glacier, South Georgia Island

The Neumayer Glacier, on the east coast of this small island in the southern Atlantic, has shrunk more than 2.5 miles this century, according to NASA. The glacier flows into the ocean, so even a tiny change in the ocean’s temperature can have a significant effect on it.

Warmer sea-surface temperatures can expedite the retreat of tidewater glaciers by melting and calving icebergs. As this fresh water enters the ocean, it contributes to sea-level rise.

Lake Powell, Arizona and Utah

Prolonged drought coupled with water withdrawals have caused a dramatic drop in Lake Powell's water level, NASA says. These images show the northern part of the lake, which is actually a manmade reservoir extending from Arizona into southern Utah. In 1999, water levels were almost at full capacity. By May 2014, it had dropped to 42% of capacity.

Although records show droughts are a part of this region’s climate variability, the droughts are becoming more severe.

Even in “low-emission” climate scenarios (forecasts that are based on the assumption that humans’ ever-growing dependence on fossil fuels will begin to slow down and even decrease in the future), models predict precipitation may decline by 20-25% over most of California, southern Nevada and Arizona by the end of this century.

Camp Fire, California

The Camp Fire, in California’s Butte County, became the state’s deadliest and most destructive wildfire last year. It left 85 people dead and destroyed almost 14,000 homes.

Climate change caused an increase in the amount of land burned by wildfires across California in the last 50 years, according to a new study published earlier this year in the journal Earth's Future.

The cause of the increase is simple. Hotter temperatures cause drier land, which creates a parched atmosphere.

"The clearest link between California wildfire and anthropogenic climate change thus far has been via warming-driven increases in atmospheric aridity, which works to dry fuels and promote summer forest fire," the study said.

Northern Europe

These images show how a persistent heat wave in 2018 turned typically green areas brown. According to the European Space Agency, much of this region turned brown in just a month as several countries experienced record-high temperatures and low precipitation.

Heat waves like this one are just going to increase. Parts of Europe and North America could experience an extra 10 to 15 heat-wave days per degree of global warming, according to a study published in Nature.

Tigris River, Iraq

The 2019 image shows the Tigris River swollen and filled with suspended sediment, the result of an unusually wet winter and spring, NASA says. The surrounding land is also much greener than it was in 2015.

Climate change doesn’t just make everything hotter and drier. Extreme rainfall events will become more frequent and severe as the planet warms. This can lead to cases of “weather whiplash,” where extreme dry years are followed by extremely wet ones, according to scientists. That was the case in Iraq in 2019, which had far above average rainfall after years of extreme drought, causing rivers to swell well beyond their banks.

Columbia Glacier, Alaska

These images show how much the glacier has retreated over nearly three decades. The Columbia Glacier descends through the Chugach Mountains into Prince William Sound.

The retreat of the Columbia Glacier contributes to global sea-level rise, as the glacier melts and creates icebergs. This one glacier accounts for nearly half of the ice loss in the Chugach Mountains, says NASA.

Theewaterskloof reservoir, South Africa

Theewaterskloof, the largest reservoir in South Africa’s Western Cape province, was at full capacity in October 2014. But because of a drought, it plummeted to 27% of capacity in October 2017.

Speaking to CNN in 2017, Cape Town Executive Mayor Patricia de Lille explained her concerns about the water crisis: “Climate change is a reality and we cannot depend on rainwater alone to fill our dams, but must look at alternative sources like desalination and underground aquifers."

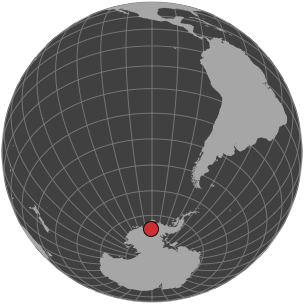

Pine Island Glacier, Antarctica

Iceberg B-46 started breaking off of the Pine Island Glacier in October 2018. It may look small here in the second photo, but it’s actually 115 square miles. The glacier has been calving more and more icebergs in recent years, NASA says.

Scientists are watching Pine Island Glacier closely because of its thinning, retreat and contribution to sea-level rise.

Lake Aculeo, Chile

This lake in central Chile dried up last year. By March 2019, it consisted of dried mud and green vegetation. Scientists attribute it to a decade-long drought coupled with increased water consumption from a growing population.

This megadrought had many contributing factors, but scientists say that about a quarter of its severity and intensity can be attributed to global warming.

Hurricane Harvey aftermath, Houston

The second image here shows the extensive flooding caused by Hurricane Harvey in August 2017. Both images were made with a combination of visible and infrared light that highlights the presence of water on the ground.

Human-caused climate change made the rainfall from Harvey, which dumped more than 19 trillion gallons of water and brought devastating floods to the Houston area, roughly three times more likely to occur and 15% more intense, according to World Weather Attribution, an international coalition of scientists led by nonprofit scientific research group Climate Central.

Sudirman Range, New Guinea

The tallest peaks of this mountain range have been cold enough to support glaciers, NASA says, but the ice has diminished dramatically over the years.

Tropical glaciers like this one are shrinking across the world. Scientists estimate these glaciers could be gone within about a decade.

Okjökull glacier, Iceland

This once-iconic glacier, seen on the far left, was declared dead in 2014, NASA says. Only small patches of thin ice remain.

Scientists bid farewell to Okjökull, the first Icelandic glacier lost to climate change, in a funeral of sorts earlier this year.

The inscription on the monument, "A letter to the future," paints a bleak picture.

"Ok is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. In the next 200 years, all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and know what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it," the plaque reads in English and Icelandic.

Photo editors: Kyle Almond, Brett Roegiers, Bernadette Tuazon

Design and development: Curt Merrill, Sean O'Key