Schulz and 'Peanuts' still inspire wonder

(CNN) — “Peanuts” is everywhere.

On Friday, “The Peanuts Movie,” a feature-length film featuring Charlie Brown, Snoopy and the gang from Charles M. Schulz’s long-running strip, opens across America.

That’s the latest addition to the holiday specials, Christmas stamps, commercial ventures, figurines and — oh, yeah — 65-year-old comic strip starring the legendary group of characters.

A new book, “Only What’s Necessary: Charles M. Schulz and the Art of Peanuts,” highlights Schulz’s contributions to the culture. They’re substantial, author Chip Kidd says.

Kidd also oversaw the assemblage of detail from the Schulz archives, which includes Schulz’s correspondence, promotional materials for the strip, “Peanuts” merchandise and Schulz’s painstaking (and sometimes abandoned) sketches.

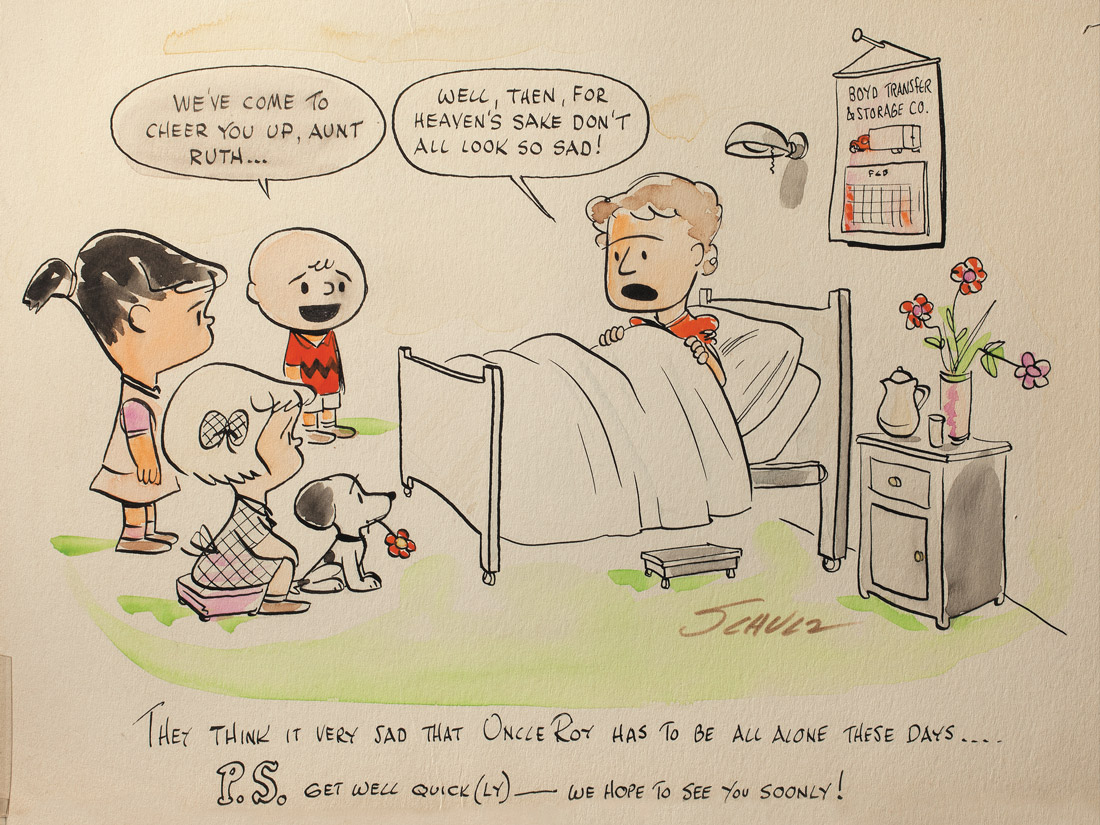

A get-well card for Schulz's Aunt Ruth.

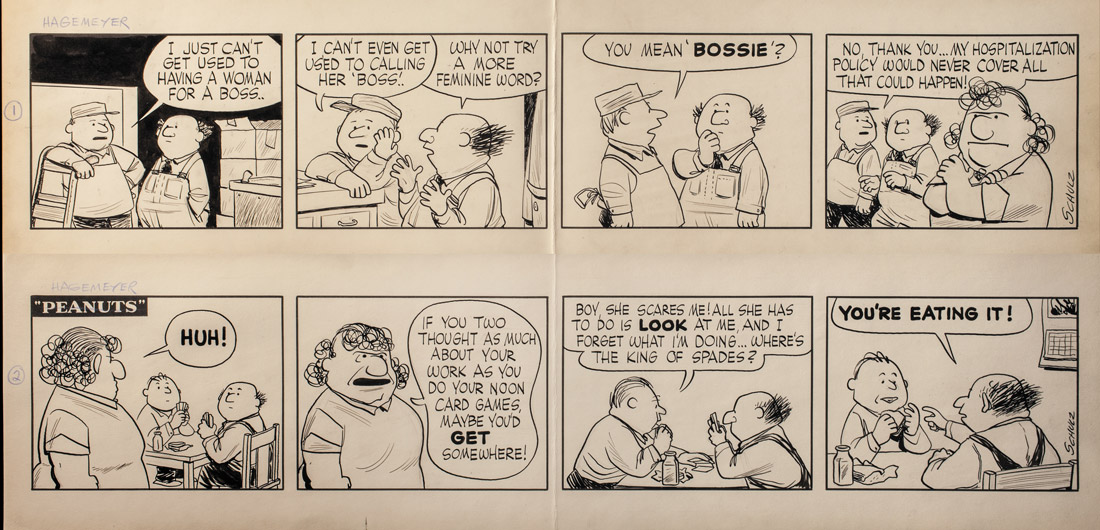

Schulz tried his hand at another strip, “Hagemeyer," after “Peanuts” became successful.

“To me, it’s like, why do people read ‘Tom Sawyer’ again and again throughout the generations?” asked Kidd, also a renowned artist in his own right. “A really great piece of literature transcends generations.”

The breadth of Schulz’s imagination is still astonishing to contemplate.

“Peanuts” began October 2, 1950, in seven newspapers. It was a quietly amusing strip focused on children, though with an awareness that could come only from an adult: “Good ol’ Charlie Brown,” a boy says in the very first strip as our hero walks by. “How I hate him.”

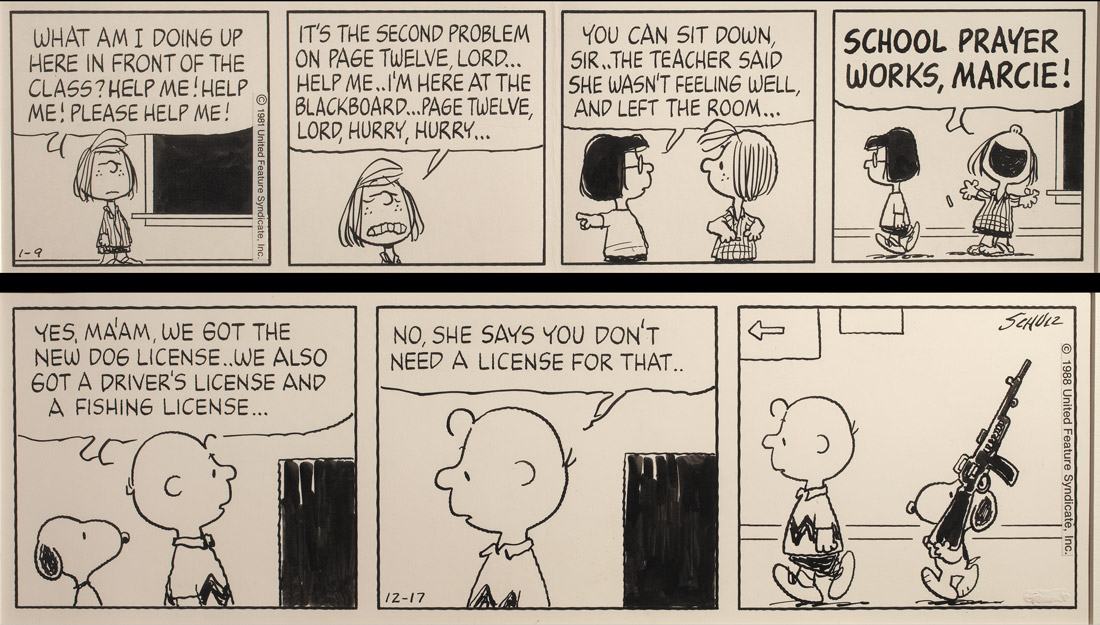

Over the years, its subjects expanded to include, essentially, the whole of human experience: religion and psychology, history and literature, the pain of disappointment and the joy of triumph (though the latter, sadly, never came for Charlie Brown).

And politics.

The Great Pumpkin, Joe Shlabotnik, Lucy’s help booth — all sprung from Schulz’s mind. He invested Snoopy, in the beginning Charlie Brown’s almost-silent canine companion, with a life as detailed as the never-seen interior of his seemingly humble doghouse: battling the Red Baron, lamenting the loss of his Van Gogh.

No wonder magazines put “Peanuts” on their covers. No wonder whole chin-stroking books have been written on its significance.

Schulz himself was aware of the power of his creation, though he claimed the strip was, essentially, about disappointment. "All the loves in the strip are unrequited; all the baseball games are lost; all the test scores are D-minuses; the Great Pumpkin never comes; and the football is always pulled away," he once said.

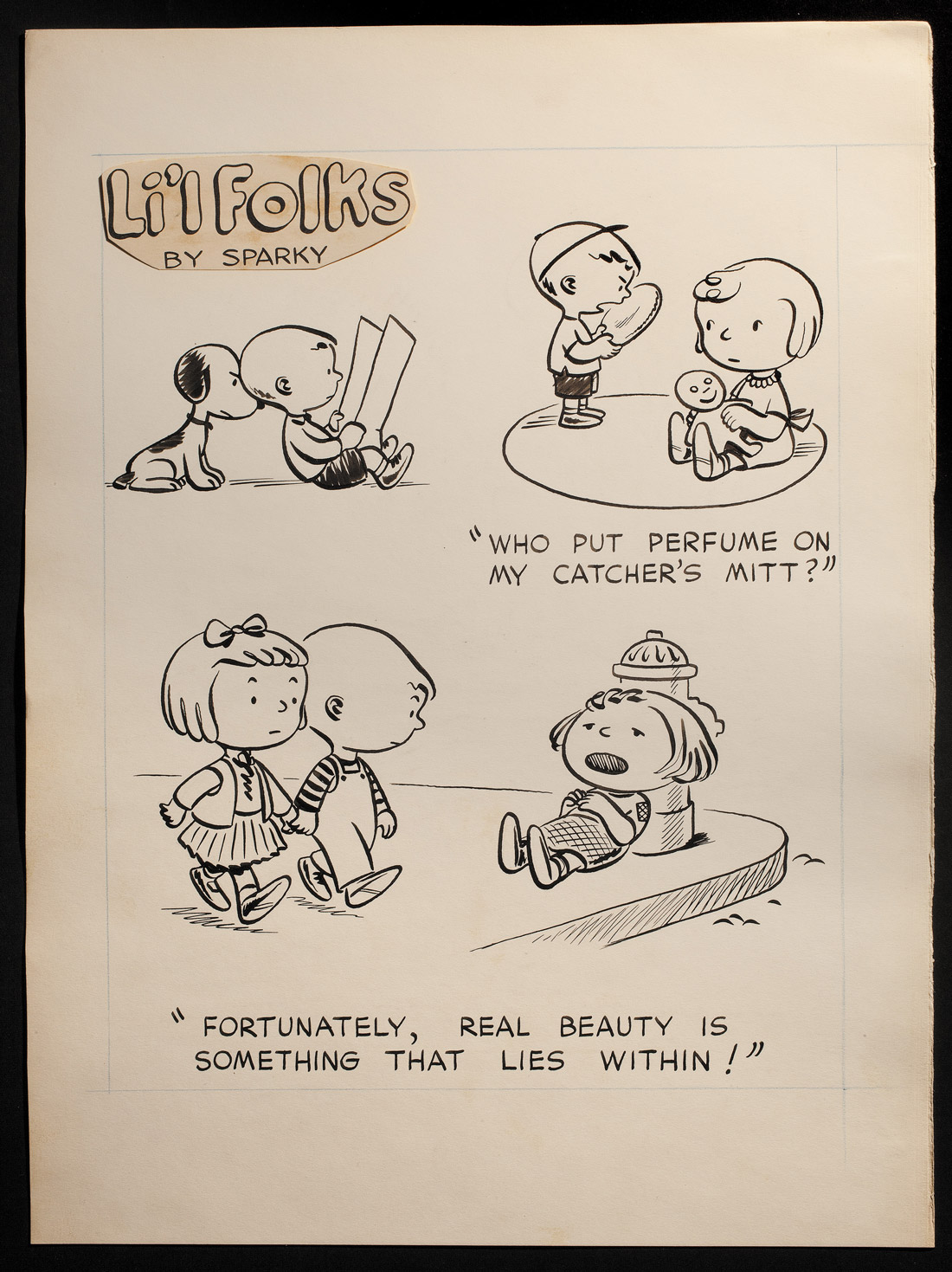

Among the most revelatory finds in “Only What’s Necessary” are what Kidd calls the “missing links”: early strips that show the transition from “Li’l Folks” (the original version of “Peanuts”) to the strip that eventually appeared in newspapers.

The range of Schulz’s imagination can take away from the brilliance of his art. He could say so much with just a few lines, but the simplicity of his drawing – and the fact that it was shrunk for use in more than 2,500 newspapers – could diminish the perception of his skill.

“I never cease to be amazed and delighted to see actual, original art,” Kidd said.

Schulz himself could be modest about his capabilities, comparing himself unfavorably with artists such as Andrew Wyeth. Ironically, Wyeth was a fan: "I have been thinking of you and your very remarkable quality of expressing in simple, direct statements the American way of life," the painter wrote to the cartoonist in late 1999.

Schulz’s success also invited criticism. Kidd observes that some fans turned against the strip in the late ‘50s when Schulz signed a marketing deal with Ford Motor Co.

Years later, Mad magazine did a wicked parody in which Charlie Brown was depicted as an avaricious, toupee-clad businessman.

But, says Kidd, there was the newspaper strip, and then there was everything else.

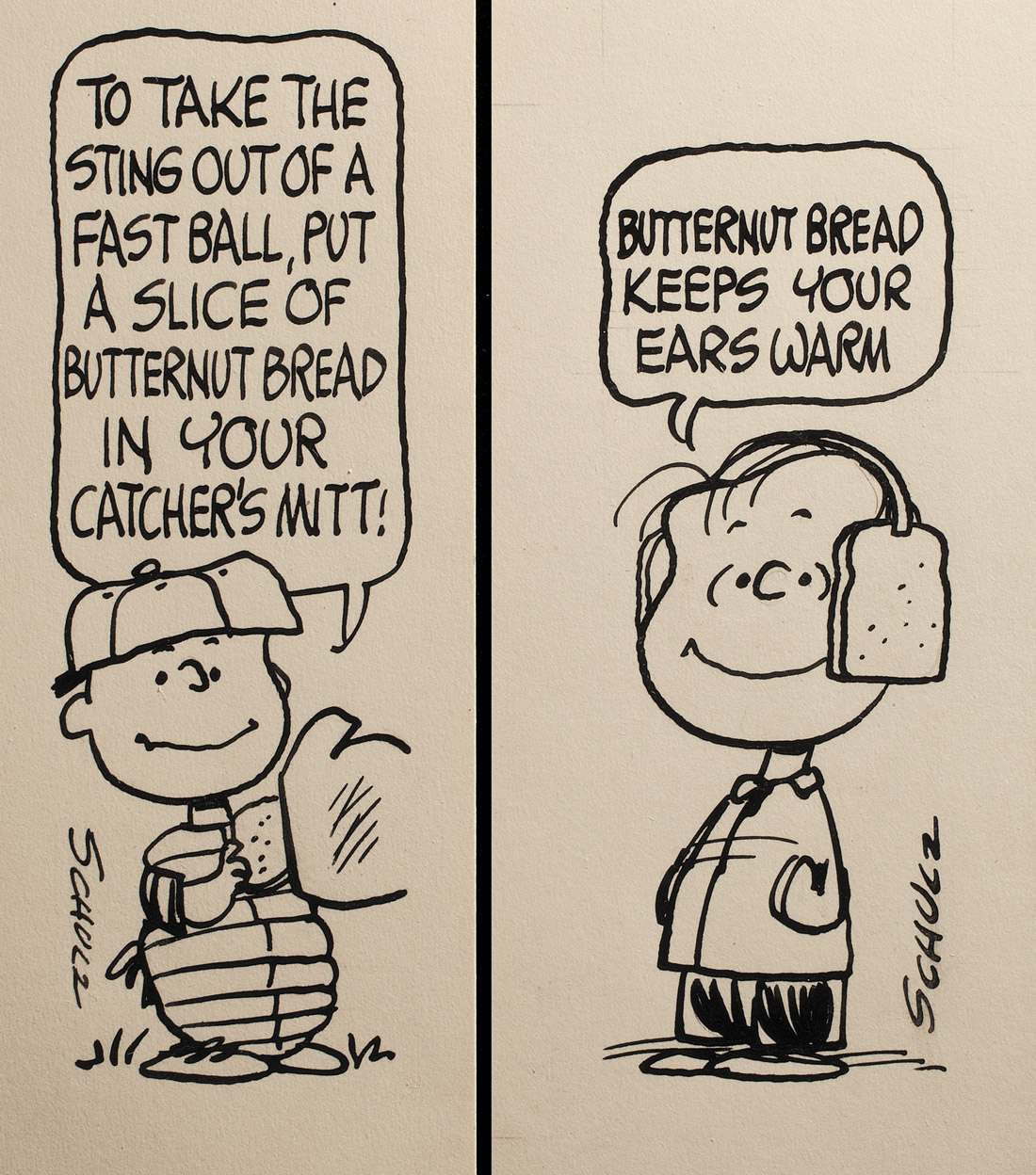

An ad for Butternut Bread.

“Schulz very much compartmentalized the strip itself, (which) was number one. Only he could write and draw it, and he put the proviso in his will that when he was gone, the ‘Peanuts’ strip would be done,” he said.

“But then there was all the licensing and the TV specials and the movies and cartoons and all of that, and he did look at all of that very pragmatically, in that ‘I’ve got five kids and a household, and they’re all depending on me,’ ” he added. “It certainly wasn’t anything goes, but he was certainly open (to options).”

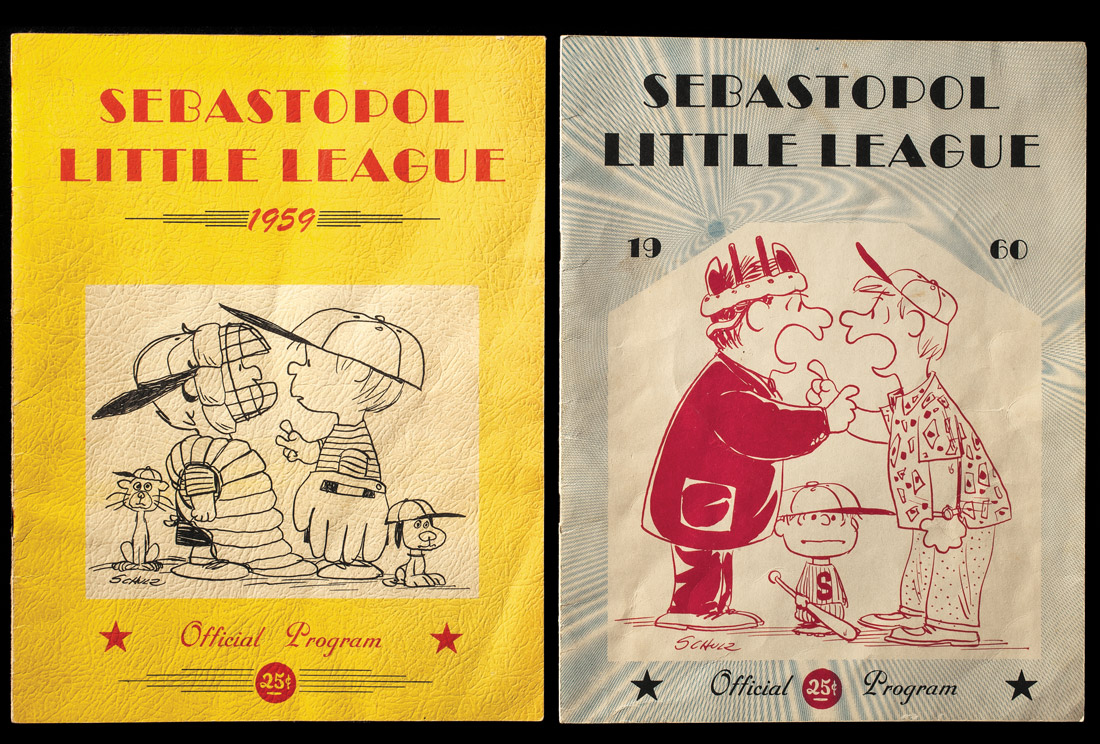

Schulz did the program for a local Little League.

It hasn’t lessened appreciation of the strip in the present day, 15 years after Schulz died – poetically, the day before his final original strip ran.

As the material in “Only What’s Necessary” reveals, you can never get to the bottom of “Peanuts,” says Kidd.

“The range and depth of all the different ‘Peanuts’ characters ... the way the characters evolved and this whole affectation that they were children but everybody knew they weren’t. It’s really fascinating,” he said.

So you’re not such a loser, Charlie Brown — even if, of all the Charlie Browns in the world, you’re still the Charlie Browniest.

Photographs Copyright 2015 Peanuts Worldwide LLC, courtesy of the Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center, Santa Rosa, California