Yogi Berra famously said “It ain’t over ‘til it’s over,” but one of the greatest careers in baseball history might have been over before it had even begun.

In 1944, two years before he started launching home runs at the Yankee Stadium, Berra was on a rocket boat off the coast of Normandy, providing cover fire for the D-Day Invasion.

He was injured during the attack, he pulled bodies out of the water, and he learned that in comparison to war, baseball would be easy.

During his remarkable 90 years of life, Berra became many wonderful things to many different people; he was universally loved, but he was the most revered by a special few, his family.

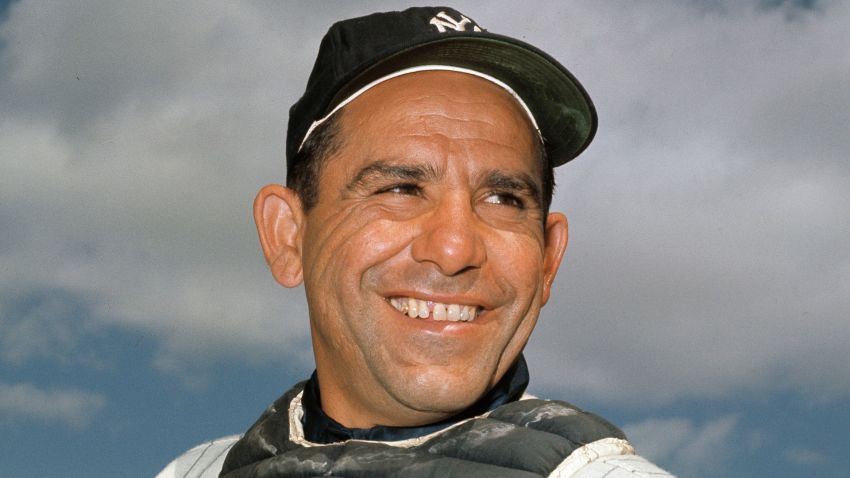

“For me, Yogi Berra was my grandpa,” his granddaughter Lindsay told CNN, “He was the guy who burned all the hot dogs at our family barbecues when I was a kid. But to the rest of the world, I mean, I think he was arguably the greatest catcher of all time!”

Berra’s list of accomplishments as a ballplayer are so extensive that they hardly seem credible.

He won so many World Series rings with the Yankees that he had one for every finger, then he won three more as a coach to bring the total to 13.

“He had one of the greatest World Series resumes, of any player, ever,” remarked the legendary US broadcaster, Bob Costas.

He was the American League’s MVP three times, and he made 18 appearances in the All-Star game.

“Many of his records will never be broken,” says Lindsay. “The proof was in the pudding.”

A baseball catcher is often compared to a football quarterback; as the only player with a complete view of the field, it’s the catcher who communicates with the pitcher and sets up each play.

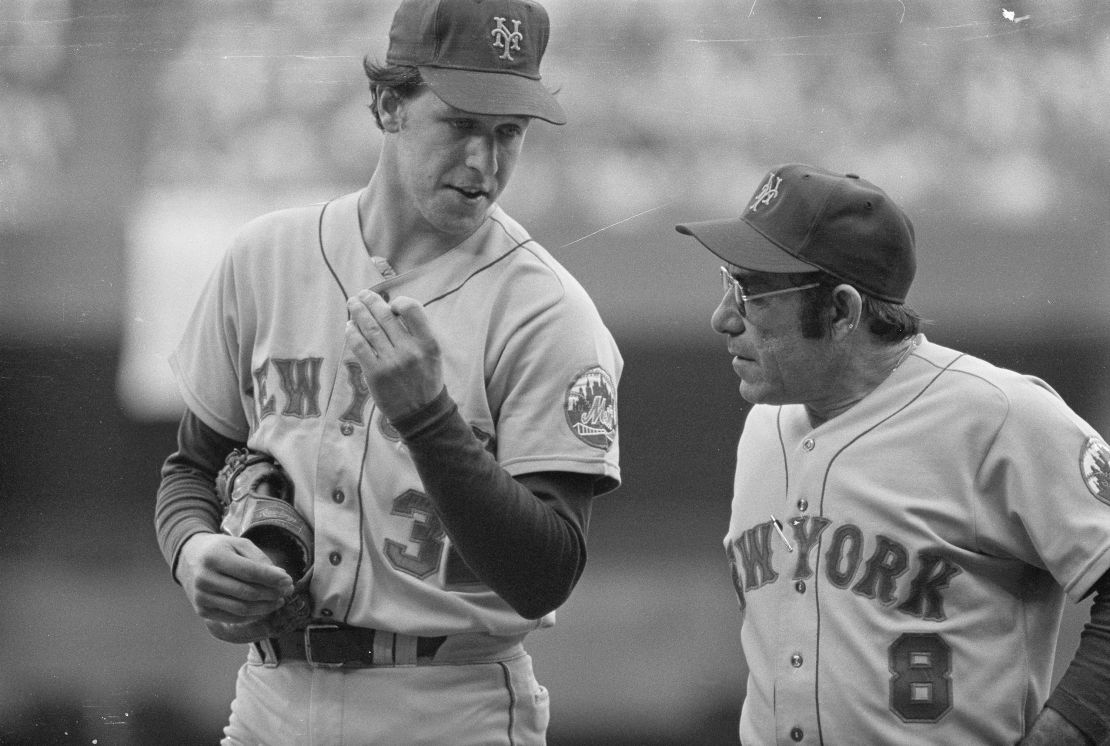

In 1956, Berra helped the Yankees pitcher Don Larsen to throw the first, and still only, perfect game in the World Series. And yet, Berra somehow became his sport’s forgotten man.

As the actor Billy Crystal put it, “He was the most overlooked superstar in the history of baseball.”

A new documentary film, now playing at movie theaters across the US, is trying to recalibrate the narrative. Fittingly entitled, “It Ain’t Over,” the movie’s producers are hoping that his legacy can be re-evaluated by a new generation of sports fans.

Lindsay notes that the 1950s media portrayed Yogi as more of a caricature than an athlete.

“They certainly went after his appearance in a way that I find somewhat appalling,” she explained. “They said he looked like an ape and a gargoyle and a fire hydrant, and Life Magazine said he looked like a fat girl running in a too-tight skirt.

“One paper wrote that he was too ugly to be a Yankee, I don’t even know what that means. And quite frankly, he was pretty handsome as a young man.

“They say that the jester can never be king. I think in portraying him as this kind of ugly, goofy, funny guy, it did downplay his achievements on the field. The press went with the funny part, and not the great part.”

If anything was ugly, it was the mood of the pitchers whose offerings pitches that he still managed to club all over the ballparks in the American league.

Berra famously said that the pitches “all looked good to me,” swinging at balls that were often well out of the designated strike zone.

In baseball, as in life, he had an uncanny ability to make lemonade out of lemons. Observers said that his strike zone seemed to be anywhere between his ankles and his nose, and he would instinctively adapt his swing to smash low balls away for deep home runs or high pitches for line drives.

That’s perhaps how he was able to hit 358 home runs and drive in 1,430 runs, a major league record for a catcher, in his career, and he never struck out more than 38 times in a single season.

For seven consecutive years, he led the Yankees for in RBIs (runs batted in), a Yankees team that included Joe Di Maggio and Mickey Mantle – both of whom are considered all-time greats.

If Berra was bothered by the media’s obsession with his looks, he never showed it.

“I never saw anyone hit with his face,” he’d quip.

Lindsay noted that her grandfather’s experience in the war had armed him with a shield that seemed to protect him against any perceived slights in later life.

“He was incredibly grateful to be playing a kids’ game for a living and making money from something he loved. I don’t think anything that anyone said or wrote took any of that joy away from him. He was always telling us how blessed he was.”

But if the media wasn’t in love with his looks, he soon charmed them with his words, and by 1959 Sports Illustrated was reporting that his personality was overshadowing his exploits on the field.

When Berra stopped playing in 1965 and moved into coaching and managing, he had more time for the reporters who learned to appreciate him for his wisdom.

Berra became known for his “Yogi-isms,” one-liners which are still quoted over half a century later.

“Sometimes they sound a little silly on the surface,” Lindsay told CNN, “but if you think about them, they’re quite profound and quite genius. He was able to cut through all the crap, and he had this very direct, black and white view of the world.

“My favorites are the existential ones,” she said: ‘If the world were perfect, it wouldn’t be,’ ‘the future ain’t what it used to be,’ ‘we’re lost but we’re making good time.’”

Also often quoted is his Berra’s line about a restaurant that’s become so popular that it’s no longer attractive: “Nobody goes there anymore; it’s too crowded,” he famously uttered.

“There’s just so many of them,” concludes his granddaughter, who relates that he became so famous for his pithy remarks that people would expect him to produce them on command.

“People would say, ‘Oh, you said another one,’” she chuckled, “And he would say, ‘I don’t even know I say them.’ It was just the way that he talked, they just sort of fell out of his mouth.”

While her grandpa was still alive, Lindsay wrote for ESPN’s ‘The Magazine,’ and he’d always make a point of reading her articles. He was particularly taken with her profile of a male tennis player, who he thought would make a good match for her.

“This kid is good looking, you should date him,” he stated. “I can’t date him Grandpa,” she replied, “he dates a swimsuit model.

“And he said, ‘Well, you’ve got swimsuits!’ And in his mind, there was no difference between me in a swimsuit, and a swimsuit model, but that was just the beauty of his logic.”

As a member of what is often referred to as the greatest generation, Berra returned from the war to find his own country involved in another struggle, the fight for civil rights.

Berra met Jackie Robinson while they were both playing in the minor leagues in 1946. When Robinson broke the color barrier the following year, Berra was only too happy to welcome him into the game.

“Grandpa had served with Black soldiers in World War II,”Lindsay explained, “and I don’t think he went to Europe to fight for the freedoms of French people to watch those same freedoms denied to Americans at home.”

They were rivals and friends, and Robinson’s dramatic steal of home in Game One of the 1955 World Series was something they would argue about for the rest of their lives. Berra always maintained that he’d tagged Robinson and that the Dodgers star should have been called out.

“He was great friends with Jackie. I don’t think Grandpa meant to be a civil rights activist,” explained Lindsay, “He just did the right thing. And that’s super important because I don’t think the country gets where it got with the civil rights movement if baseball doesn’t go there first.”

In their own different ways, both these players are iconic, and by the time he’d spent many years starring in commercials, promoting everything from chocolate drinks to cigarettes and credit cards, Berra was firmly established in American pop culture.

And yet, he never got the recognition that his family felt that he deserved.

Some of the reasons were accidental; for example, once he’d been wounded in combat, he was eligible to receive a Purple Heart medal, but he never filled out the paperwork – he didn’t want his mother to receive a telegram that he’d been hurt and start to worry.

Lindsay has spent more than a decade trying to secure the medal, without success.

She learned that she needed to be in possession of his discharge papers from the army, but that they were burned in an archives fire in 1973. Then she was informed that they hadn’t been burned, but nobody could find them.

Her hopes were then lifted and dashed again, “In Maryland, they have every Purple Heart card from World War I through the Gulf War, with the exception of World War II from A through C. I mean, what are the odds of that?”

The family persisted, though, and shortly after Berra’s death in 2015, he was recognized with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Speaking at The White House, then US President Barack Obama quoted one of his many famous lines: “If you can’t imitate him, don’t copy him.”

Nobody could ever successfully copy Berra, but for anyone who wants to try, his family wants the full picture to be known.

“My goal with the documentary,” concludes Lindsay, “is to show that as good as he was on the baseball field, he was actually an even better human being.”

“You can observe a lot just by watching,” he once said, and it might be that with the advent of “It Ain’t Over,” the legacy of Berra will now never be over.