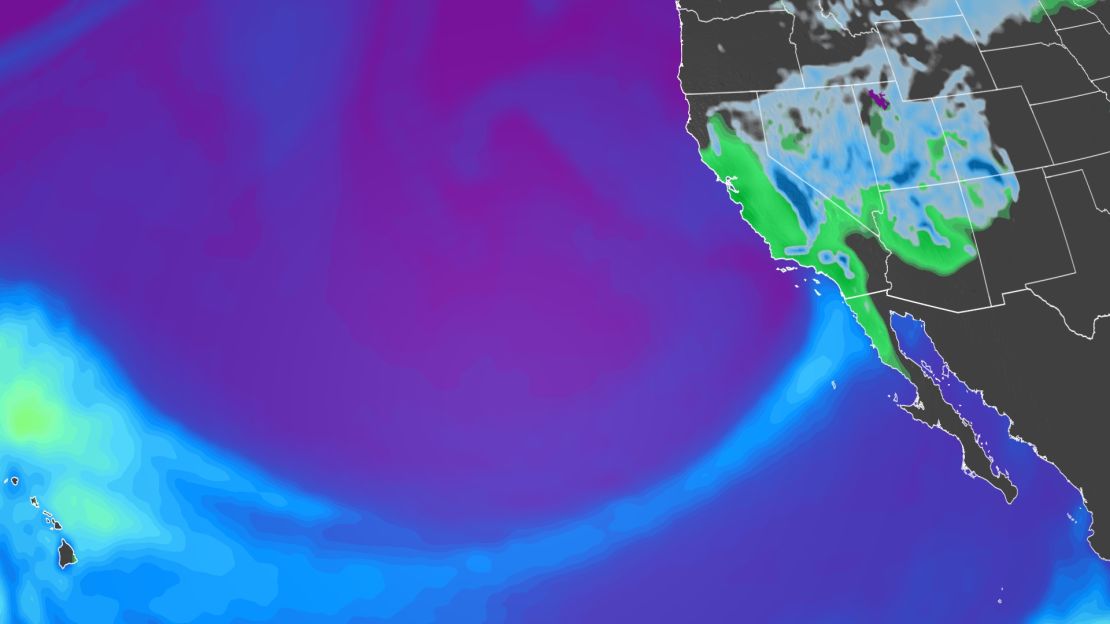

California is bracing for yet another powerful, atmospheric river storm this week, continuing the onslaught of major weather whiplash after a yearslong, historic megadrought.

Many welcomed this winter’s heavy rain and snow since it was so desperately needed to replenish the state’s severely drained reservoirs and depleted groundwater.

But the storms kept coming. California is now facing its 12th significant atmospheric river since the parade of strong storms began in late December.

“This is an unusually high number of storms this winter in California,” said Daniel Swain, climate scientist at the University of California at Los Angeles. “No matter how you slice it, no matter how you make these formal definitions, this is unusually many.”

Determining how to count atmospheric rivers is an ongoing conversation in the scientific community.

While Swain said California has seen 12 significant atmospheric rivers so far this season, Chad Hecht, a meteorologist with the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes (CW3E) at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, said the center has tallied of 29 so far, including some weaker systems and systems that only clipped California. Six of the storms fell into the category of what Hecht described as severe or extreme.

“These numbers are likely higher than a lot of the numbers you are seeing from news outlets because their criteria for an atmospheric river is likely stricter and considers the impacts that they bring,” Hecht said. “There are [also] instances when an atmospheric river is primarily targeting the Pacific Northwest, but clips the far northwestern portions of California, say Del Norte County, with weak conditions.”

Weak and low-end moderate storms tend to be less impactful and primarily bring beneficial precipitation to the state, he said. Meanwhile, the high-end atmospheric rivers are the big rain and snow producers, which lead to more severe impacts.

Hecht said this year has already outpaced the state’s average annual number of atmospheric rivers. Many of them came in a rapid series of storms in early January.

“We typically refer to these successive types of atmospheric rivers as ‘AR families,’” Hecht told CNN. “While AR families are not all that uncommon, we don’t see them every year and the stretch of nine we had around the turn of the New Year was a more active family than we typically see.”

While the barrage of rain and snow has alleviated the drought, the storms have also been destructive and deadly.

An atmospheric river is like a conveyor belt of moisture that originates over the tropical water of the Pacific Ocean. They can carry more than 20 times the amount of water the Mississippi River does, but as vapor. As these storms pummeled the state in quick succession, the soil became over-saturated and vulnerable to flooding and mudslides.

It’s unclear how the climate crisis could be playing a role in the number of storms that hit the West Coast. But climate scientists have linked the climate crisis to an increase in the amount of moisture the atmosphere holds, meaning storms — such as hurricanes and atmospheric rivers that are impacting the West Coast now — will be able to bring more moisture inland than it would without climate change, which in turn leads to an increase in rainfall rates and flash flooding.

Swain said this week’s storm will be another event that will rapidly strengthen and could even come close to what’s known as a “bomb cyclone” — a storm that rapidly intensifies at a rate of at least 24 millibars of pressure in 24 hours. The storm is expected to affect a large area of the California coast, from the San Francisco Bay Area to Southern California.

“This [storm] is going to bring a whole litany of concerns that are probably greater than we had initially anticipated a few days ago,” Swain said. “Frankly, even widespread moderate rain at this point is going to exacerbate flood conditions in some places — so not the best news.”

Despite these hazards, Swain said that California is lucky to have some breaks in between the storm cycles. And forecasters with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported last week that they expect the West’s spigot of rain and snow will likely turn off come April.

“As much as folks feel like it’s been an unrelenting winter, we actually have gotten some at least weeklong breaks and, in some cases, multi-weeklong breaks in between these sequences,” he said. “Had we had this winter and everything that happened back-to-back without any breaks during the storm cycles at all, the level of flooding and the level of damage in California would be dramatically higher.”

The storms have also erased the dire impacts of the drought, particularly mandatory water cuts in parts of the state.

According to the latest US Drought Monitor, severe drought now only covers 8% of the state, with just over a third of the state remaining in some level of drought — the lowest amount in nearly three years.