Editor’s Note: Chloë Grande is an eating disorder recovery blogger, writer and speaker. Find her online at www.chloegrande.com. The views expressed in this commentary are her own. View more opinion on CNN.

In the middle of a Zoom call in the spring of 2020, I was hit with a sudden dizzy spell. Intense gut pain sent me rushing to the bathroom of my small basement apartment. My heart pounded and sweat beads formed along my brow. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to vomit, cry or curl up in bed. The pain intensified. I broke down sobbing on the cold bathroom tiles.

What felt like a panic attack was, in fact, the beginning of an eating disorder relapse. The symptoms were familiar: intense mood swings, gastrointestinal issues, feeling cold, social withdrawal and difficulties sleeping. I wrote in my journal that I felt “ugly and unworthy.”

Since the start of the pandemic, the United States and Canada, where I live, have seen alarming trends in eating disorders: increased hospitalization rates for eating disorder patients and countless more people suffering in silence.

Eating disorders are one of the deadliest mental illnesses, according to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, second only to opioid use disorder, due to the medical complications and high risk of suicide.

While the focus on rising diagnoses has primarily been on young girls, adults aren’t immune to the dangers of eating disorders.

I know firsthand, as someone who relapsed with anorexia over the pandemic and felt ill-prepared to find treatment that wasn’t family-based – the gold standard of care for children and adolescents with eating disorders – and what I received as a 15-year-old.

Later in the spring of 2020, as my symptoms worsened, I searched for help and realized how few options were available. Many hospital-based eating disorder programs were shuttered or drastically downsized, and an in-person visit to my doctor was out of the question. The most promising solution was paying out-of-pocket for teletherapy with a psychologist specializing in eating disorders. Thanks to financial help from my family, I picked that option, hoping for the best.

There is no miracle cure for anorexia. There is no pill to magically rewire the brain. Instead, individuals with eating disorders rely on a medley of treatment options: psychotherapy, nutrition management, medical oversight, counselling and psychiatric medication to treat underlying mood disorders.

Eating disorders are notoriously stubborn illnesses to treat, especially when they become more severe and long-lasting.

However, new research findings show that screening for abnormal electrolyte levels may help identify those at risk for developing eating disorders. According to the study published in JAMA Open Network, participants with electrolyte abnormalities were twice as likely to be later diagnosed with an eating disorder.

I can’t help but think back to my teenage self and wonder: Could my eating disorder have been caught sooner? And if so, how would my life look different today?

My eating disorder robbed me of many precious moments. The joy of trying new foods on vacation, the spontaneity of ordering late-night takeout, the fun of exercising for the sake of feeling better and not punishing myself. I feel sadness for what could have been a much higher quality of life as a teenager and young adult.

Yet, I feel hopeful for all the people who may have their disordered eating caught before it becomes a full-blown, all-consuming, life-threatening mental illness.

But still, our societal understanding of eating disorders is limited. The loneliness of Covid lockdown and increase in social media usage are oversimplified ways to explain the surge in eating disorder diagnoses. These illnesses thrive in times of chaos, confusion and trauma.

Remember how fixated we became with productivity, this idea of coming out of lockdown with a new project, hobby or body? I lost track of how many pandemic glow-up videos came across my TikTok’s “For You” page (“Show what you looked like in 2019, then show what you look like now!”).

There was also unsettling anxiety around gaining weight, nicknamed the “quarantine 15” or “Covid 15” – another form of fatphobia.

Not to mention the body dysmorphia taking place from staring at reflections of ourselves on Zoom. Had that wrinkle existed before? Were my eyes symmetrical? Dissatisfaction with facial features can easily trickle down to other parts of our body, until we’re trapped in a pit of self-loathing.

When everything seems overwhelmingly terrifying, coping mechanisms kick in. Obsessing over food and body image can be a great distraction from other issues, especially if you’re someone like me, who had lingering eating disorder symptoms brewing below the surface for many years.

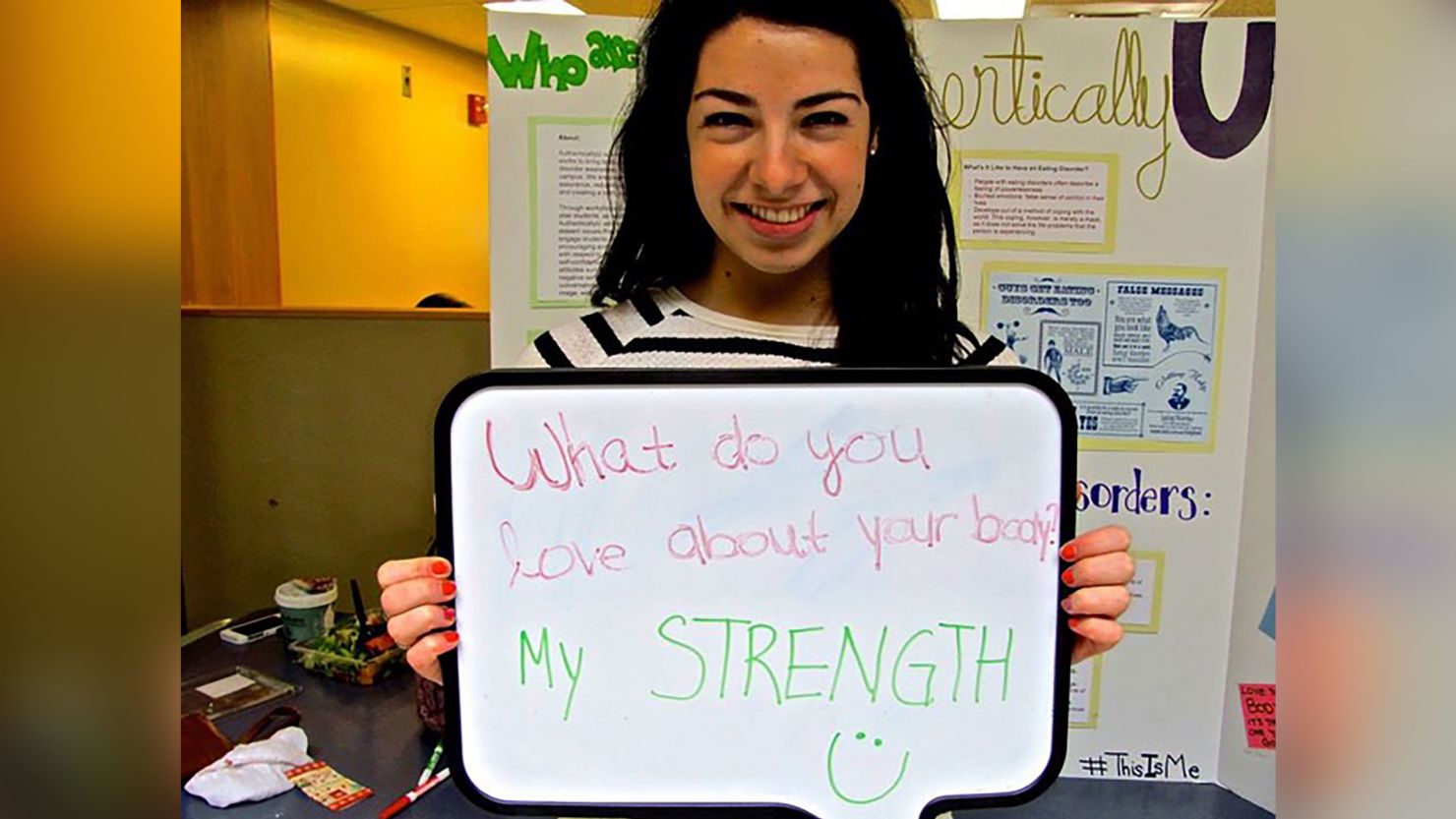

Given the sharp rise in eating disorders, we need to do more to treat the underlying culture that fuels this mental illness. How is it okay to talk about dieting, compulsive exercise or holiday weight-loss tricks, but discussing lived eating disorder experiences is taboo? The stigma is deeply ingrained, and worse for those who don’t fit the thin, white, anorexia stereotype.

Since I began blogging about my own anorexia relapse and recovery, I’ve seen the impact of hopeful storytelling that’s done in a responsible, mindful way. It’s likely we all know someone impacted by an eating disorder, and these individuals deserve empathy and compassion. I know I did.

If you or someone you know might be struggling with an eating disorder, call the National Eating Disorders Association helpline (800-931-2237) for support. If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, call or text 988, the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.