A few blocks from the Ohio State University campus in Columbus, America’s battle over abortion is playing out under one roof.

On one side of a squat single-story office building, a Planned Parenthood clinic offers reproductive health care and refers patients for abortions. Next door is a branch of Pregnancy Decision Health Center, a crisis pregnancy center that offers counseling and support for pregnant women – but also works to dissuade them from terminating their pregnancies and has been accused of promoting misinformation about abortion.

Of the two neighboring organizations, only Planned Parenthood provides medical services such as Pap smears, birth control and STD treatments.

But the crisis pregnancy center is the one receiving money from the state government. Ohio has funneled nearly $14 million in taxpayer funds to the center and others like it over the last decade, according to government records – even as state leaders have cut funding that previously went to Planned Parenthood for programs such as breast and cervical cancer screenings.

Ohio isn’t alone. More than a dozen states devote some of their budget to funding crisis pregnancy centers, a CNN review found. About half of those states distribute federal money intended to help needy families to the centers.

Some of the organizations that receive money have been accused of spreading abortion misinformation or using the funds to advocate anti-abortion causes instead of helping women.

“Public dollars should go to promoting public health,” said Ashley Underwood, the director of Equity Forward, an abortion rights advocacy group. Crisis pregnancy centers, she said, “solely exist to deter people from getting abortion services.”

Since the US Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade this summer, a wave of abortion restrictions has swept the country, leaving millions of women with easier access to crisis pregnancy centers than abortion care. Crisis pregnancy centers far outnumbered abortion clinics across the US even before the court’s ruling, and anti-abortion groups are now planning to expand.

Pregnancy center leaders and their state government allies say the organizations deserve taxpayer funds because they provide pregnant women with resources like free diapers and ultrasounds. But some of the centers also lie to women about the safety and potential risks of abortion, according to multiple studies, abortion rights activists, and women who have been to the centers.

That kind of deception isn’t typical in any other area of health care, said Dr. Amy Addante, an Illinois OB-GYN who performs abortions and has been a vocal critic of crisis pregnancy centers.

“The purpose of these centers is to try to stop someone from having an abortion,” said Addante. “I cannot think of any other medical decision or any other aspect of health care where there is a group of individuals whose only intent is to stop you from receiving that health care.”

Abortion divide runs between neighboring clinics

Big open windows invite patients and passersby into the waiting room at the Pregnancy Decision Health Center (PDHC). With velvety green chairs, leafy plants, and a coffee station that greets visitors as they come in the door, the crisis pregnancy center could pass for an upscale dental office or spa.

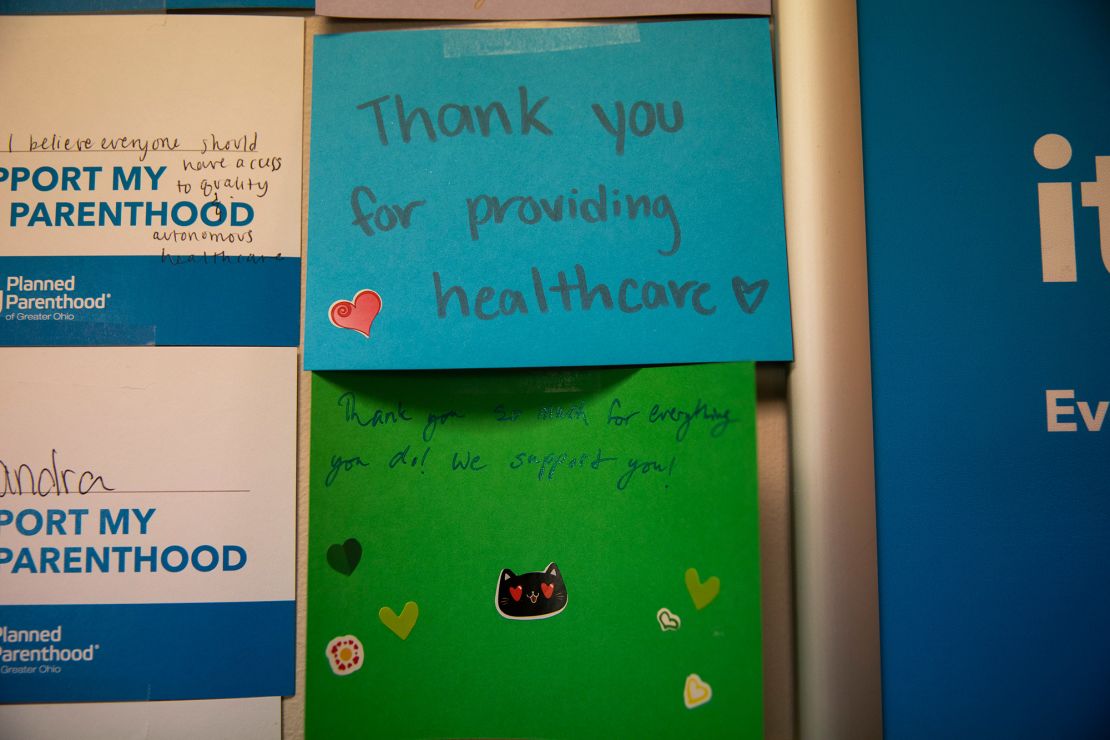

Outside, PDHC’s sign towers over the neighboring Planned Parenthood, literally casting a shadow over the clinic’s entrance. Inside, the contrast is even starker: Planned Parenthood’s waiting room looks run-down – old chairs crowd the small space, faded informational posters cover the walls, and daylight is blocked by signage on the windows and mirrored doors meant to protect patients’ privacy.

Multiple times a week, patients looking for Planned Parenthood mistakenly walk through PDHC’s doors, according to a Planned Parenthood clinician, Jennifer, who asked CNN not to use her last name out of security concerns. Some patients have told Planned Parenthood that PDHC employees told them abortion wasn’t safe or said PDHC tried to delay them and make them late for their Planned Parenthood appointments.

“They’ve provided an array of misinformation, whether it’s about abortion care or even about contraceptive services,” said Lillian Williams, the vice president of health services of Planned Parenthood of Greater Ohio.

Ayla Krueger, a 23-year-old Columbus resident, visited PDHC earlier this month with a friend who was seeking an STD test. She said that during their hour-and-a-half visit, an employee claimed that condoms were only 50% effective, the spread of STDs could only be prevented if people followed “God’s plan” of avoiding sex before marriage, and that if a woman who has an STD gets an abortion, “your STDs travel up your cervix into your organs and could kill you.”

“I was dumbfounded,” Krueger said of the encounter. “My heart was breaking, thinking about girls who don’t understand what they’re walking into there… and possibly getting coerced.”

Experts said that the center’s rhetoric was not medically accurate. “We do worry about ascending infections in abortions and pregnancy, but the risk is really, really low,” said Dr. Jonas Swartz, an OB-GYN and professor at Duke University Medical Center. “Crisis pregnancy centers regularly overstate the risk of abortions and this is just one example of that.”

The center also offers “abortion pill reversal,” according to its website, annual reports and pamphlets at the office. Abortion reversal is a medically dubious, unproven treatment that purports to undo a medication abortion but has been denounced by medical groups and found to be dangerous by researchers. A clinical trial that attempted to study abortion reversal was halted prematurely in 2019 when several participants suffered hemorrhaging.

Kathy Scanlon, PDHC’s president, declined an interview request and didn’t respond to CNN’s questions about Krueger’s allegations or abortion pill reversal.

“Every woman deserves care and compassion when facing an unexpected pregnancy,” Scanlon wrote in an email, adding that the center provides “practical pregnancy care and support ranging from free pregnancy tests and ultrasounds to parenting education classes and much-needed baby items” such as diapers and car seats.

Research has found that crisis pregnancy centers commonly disseminate misinformation. A study released last year by The Alliance, an abortion rights advocacy group, found that almost two-thirds of crisis pregnancy centers in nine states promoted false or biased information about abortion on their websites. That included false claims that abortions increased the risk of cancer or infertility. More than a third of clinics also advertised that they offered abortion pill reversal – and state-funded clinics were more likely than privately-funded ones to offer the unproven procedure and less likely to offer prenatal care, according to the study.

Similarly, a 2012 academic study of crisis pregnancy centers in North Carolina found that 86% of centers promoted false or misleading medical information on their websites.

Crisis pregnancy center leaders say they are working to help women. Peggy Hartshorn, who founded the Columbus center and is now the chair of Heartbeat International, one of the largest global networks of crisis pregnancy centers, said the allegations that the groups spread misinformation are “a false narrative.”

She said that the information her centers provide to clients is “very well-researched, medically referenced – we document everything with multiple sources.”

“Deep down in their hearts, women do not want to have abortion,” Hartshorn said. “Pregnancy centers are good for America, they really are.”

In Ohio, a new six-week abortion ban that went into effect after the Supreme Court decision, is currently on hold amid court battles. The Planned Parenthood clinic near Ohio State University doesn’t perform abortions – it refers patients to a Planned Parenthood surgical center on the other side of town that does.

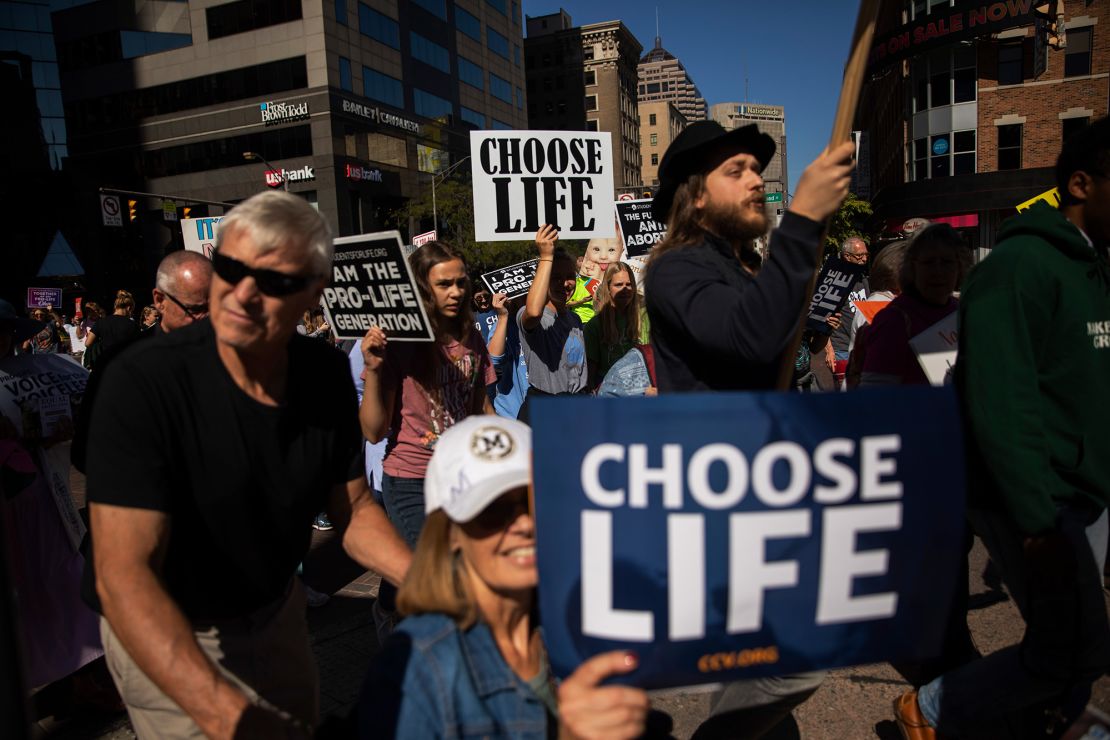

That facility, too, has a state-funded crisis pregnancy center operating across the street. On a recent afternoon, a handful of protesters lined the clinic’s fence with signs depicting bloody fetuses and shouted “you are already a mother” and “abortion is murder” whenever a patient came within earshot. One protester – wearing a reflective vest and holding a clipboard, similar to Planned Parenthood volunteers – tried to direct patients away from the abortion clinic and to the crisis pregnancy center across the street. The center told CNN the protesters weren’t affiliated with their organization.

It’s not rare for pregnancy centers to operate near abortion clinics. More than 100 pregnancy centers around the country are located within 200 meters of an abortion clinic or Planned Parenthood location, according to a CNN analysis. Some – in states like Delaware, Indiana and Michigan – are next door to clinics.

Abortion rights advocates say the intention is to mislead women and block them from accessing abortion.

“The purpose of co-locating near a legitimate provider is to intercept someone seeking legitimate health care and divert them into walking through their doors instead,” said Tara Murtha, the co-author of a report about pregnancy centers and a spokesperson for the Women’s Law Project. “It’s basically an obstacle course and a systemic barrier to abortion care.”

Anti-abortion centers raking in taxpayer funds

Despite the groups’ apparent spreading of misinformation, at least 18 states have funded crisis pregnancy centers with taxpayer money, according to a CNN review of government records and statements from state agencies. The largest is Texas, which has sent more than $200 million to the groups over the last decade.

More than a half-dozen states bankroll crisis pregnancy centers at least partly with funds from Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), a federal welfare program. Those federal funds are sent to states as a block grant, which gives state officials wide latitude in how to spend it, including on programs like “alternatives to abortion” grants for crisis pregnancy centers.

Research has shown that a smaller percentage of poor families are now receiving cash assistance from the TANF program than in previous decades.

While about 68% of families with children in poverty received cash assistance through TANF in 1996, when the program was created, that percentage declined to just 21% by 2020, according to a study by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan think tank. The percentage was even lower in some of the GOP-dominated states that use TANF funding to support crisis pregnancy centers, such as Texas and Louisiana.

“When you look at successes in reducing poverty by strengthening the safety net, cash assistance is the most effective way to help families,” said Aditi Shrivastava, who co-authored the study. “We are seeing states spend less of their money directly on cash assistance, and we don’t think that is what the program should be doing.”

In the wake of the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade, some states are piloting new efforts to fund crisis pregnancy centers. Lawmakers in Arkansas and Iowa approved state funding for such groups for the first time this year.

The states have argued that crisis pregnancy centers deserve taxpayer funding because they provide services to pregnant women in need.

“If we are going to be the most pro-life state in the union, we have to be prepared when those mothers come to a facility and they need help,” Arkansas state Rep. Robin Lundstrum said at a legislative hearing about the state’s new program earlier this year.

In Columbus, Pregnancy Decision Health Center is receiving more than $528,000 from the state government in the current fiscal year, according to government records. All of that comes from federal TANF funds. The funding amounts for about a fourth of the center’s total revenue, while the rest comes from private donations, according to the group’s most recent tax records available.

Despite the large amounts of money, there’s little oversight of how the taxpayer dollars are being used.

Many of the appropriations are written into spending bills passed by GOP-dominated state legislatures. Pennsylvania, for example, has sent more than $70 million over the last decade to crisis pregnancy centers through Real Alternatives, an anti-abortion group that distributes state funding to crisis pregnancy centers.

A 2017 report by the state auditor general found that Real Alternatives used hundreds of thousands of dollars of the money it received from Pennsylvania “to fund its activities in other states,” in what the auditor said was an example of the group “siphoning funds intended to benefit Pennsylvania women.” Real Alternatives denied the allegations in a statement, saying that they had “no basis in fact or law.”

Michigan, which had contracted with Real Alternatives to distribute funding for crisis pregnancy centers, canceled its contract after Gov. Gretchen Whitmer vetoed the funding for it in 2019. In a letter about the veto, Whitmer thanked a watchdog group that had issued a report accusing the organization of only helping a fraction of the pregnant women it had agreed to support.

Real Alternatives, which also receives TANF money from Indiana, said the Michigan report was “riddled with inaccuracies, distortions, half-truths and defamatory statements.”

A bill in the Ohio legislature that would have required crisis pregnancy centers receiving state funding to provide their clients with only medically accurate information died in committee in multiple recent legislative sessions. The state’s GOP legislative leaders did not respond to requests for comment.

Meanwhile, some of the same red states that have bankrolled crisis pregnancy centers have stripped funding from Planned Parenthood. In Ohio, for example, the group never received state funding for abortions, but for years it received money for other services like cancer screenings, STD prevention and treatment, and sex education for teens.

In 2016, however, Ohio lawmakers banned the state from funding any organization that performs abortions, and the law went into effect after it was upheld by a federal appeals court in 2019. That meant that Planned Parenthood affiliates in Ohio lost about $600,000 a year in state funding, and led to the cancellation of some of their non-abortion health programs.

While Planned Parenthood does receive some additional reimbursements through Ohio’s Medicaid program for providing non-abortion health care to people on Medicaid plans, it no longer receives state grants.

Planned Parenthood also lost additional federal funding under Title X, a program that funds birth control and reproductive health services, under a Trump administration rule. But the organization started receiving that money again this year after the Biden administration reversed the rule.

Maria Gallo, a sexual and reproductive health epidemiologist at Ohio State University, said that state funding for crisis pregnancy centers shows how conservative lawmakers prioritize anti-abortion rhetoric over medical care for women.

“It’s dangerous in part because they are legitimizing (crisis pregnancy centers),” Gallo said. “They are legitimizing that as a source of medical care when they’re not licensed medical facilities.”

Crisis centers outnumber abortion clinics

Crisis pregnancy centers drastically outnumber abortion clinics in the United States. There were 790 abortion clinics operating in 2021, compared with about 2,600 crisis pregnancy centers, according to a database compiled by Reproaction, an abortion-rights group.

That disparity is only likely to grow in the wake of the Supreme Court decision. Hartshorn, the chair of Heartbeat International, said the organization has created an online training program to help people open new pregnancy centers, especially in places without existing ones.

“We need more people, we need more places, and we need more paths to pregnancy health,” Hartshorn said.

A study by the National Center for Responsive Philanthropy found that the groups have taken in more and more money in recent years: They received over $1 billion in revenue in 2019, the most recent year data was available, compared to about $771 million in 2015.

Several women who went to state-funded crisis pregnancy centers told CNN they felt misled and manipulated by the groups, and disturbed that they were getting taxpayer money.

Last year, a woman who asked to be identified by her middle name, Eve, had just lost her job when she suspected she might be pregnant. She and her boyfriend went to Women’s Care Center in Columbus after finding the group on Google. Money was tight, and she chose the center – which is receiving more than $700,000 from the state of Ohio in the current fiscal year – because it promised free pregnancy testing.

Eve’s test was positive, and she asked the staff about an abortion. She said they handed her a pamphlet that warned her the procedure could cause infertility – though abortion doesn’t typically affect a person’s ability to become pregnant in the future. For three hours, Eve said the staff pressured her to carry the pregnancy to term.

“It became very clear that they were against abortion really quickly,” said Eve, who left the center feeling upset and later got an abortion. The center didn’t respond to questions about Eve’s visit but said in an email they are “absolutely committed to accuracy, excellence and transparency in all we do.”

One day, Eve said she hopes to have kids. But at the time, she didn’t feel financially or emotionally stable enough to have a baby.

“Nobody wants to make a decision to have an abortion,” Eve said. “And they made me feel really guilty and bad about it.”