Editor’s Note: Sign up to get our weekly column as a newsletter. We’re looking back at the strongest, smartest opinion takes of the week from CNN and other outlets.

“The unendurable is the beginning of the curve of joy.”

So says one of the characters in Djuna Barnes’s 1936 modernist novel “Nightwood,” set in the 1920s and defined by the intense grief, alienation and passion of its characters. It’s the disjointed tale of exiles seeking a place to belong and characters who talk past one another. The words they speak to each other are both emotionally horrifying and wickedly funny; without being obvious about it, Barnes uses them to question the possibility of a common language for reality, for what human beings desire – and to challenge what makes us human at all.

Is any of this sounding like 2021 to you yet?

With one unendurable, joyful year coming to an end and another one before us, this week we’re looking back to highlight some of the top social commentary and cultural criticism that helped us look hard into the darkness, bridge the gaps between us and sometimes, take hold of the light.

Poetry is not a luxury

2021 began with political upheaval and violence. But as the world looked on at President Joe Biden’s inauguration in January, poet-turned-cultural-icon Amanda Gorman read “The Hill We Climb,” and reminded us that poetry is, in the words of Audre Lorde, “a vital necessity of our existence” that galvanizes “our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action.” Ashley M. Jones, poet laureate of Alabama, invoked Lorde as she paid tribute to Gorman for affirming her “belief that art is the thing that has and will keep saving us …That quality of light where hopes and dreams can live is what this country needs.”

More on the power of poetry:

Tess Taylor: The delightful vacation you can take from your chair

Comedy isn’t canceled

In October, controversy erupted over comedian Dave Chappelle’s Netflix special “The Closer.” Critics blasted it as homophobic and transphobic and called for its removal; defenders cried “cancel culture.” Any claim that Chappelle is a victim of cancel culture is ridiculous, wrote Clay Cane, who observed: “As a Black gay man, I exist between two communities. There is the White queer community, many corners of which are steeped in racism, and the Black community, which sometimes reeks of homophobia. The Black gay community falls in between. Both communities can be equally delusional in their bigotry and often exalt public figures who veil their dogmatism as ‘art’ … That’s not to say Chappelle doesn’t have a right to run his mouth. On the other hand, viewers also have the right to react. It cuts both ways, but it’s critical to remember that unlike the communities who bear the brunt of his jokes, Chappelle is in no way powerless.”

Weeks later, in the shadow of high-stakes judicial uncertainty about the future of Roe v. Wade, Cecily Strong took on the role of Goober the Clown and talked about her “clown abortion” on “Saturday Night Live.” The skit was comedic greatness, wrote Judy Gold, who said as long she lives in a country where abortion is judged and restricted, she’ll keep pressing play on the video of Strong: “If it’s true what Cole Porter wrote, ‘Be a clown, be a clown, all the world loves a clown,’ then maybe we should use clowns to give a voice to other women whose stories we don’t feel comfortable talking about. Think about it. Rufie the Date Rape Clown. Boobie the Breast Cancer Clown. Reese the Restraining Order Clown. Shari the Sharia Law Clown. Melanie the Menopause Clown. Penny the Gender Pay Gap Clown who only makes 80 cents for every dollar Bozo makes. Where are the clowns? Send in the clowns.”

More smart takes on cancel culture:

Jill Filipovic: The real reason for the Dr. Seuss freakout

David M. Perry: Why I hope my kids never read Roald Dahl

Sara Stewart: The end of fandom may be here

Who are the heroes we need the most?

Why do we keep going back to a particular world created for us on the page, or on the screen? Many of us are looking for heroes. Sometimes, we want superheroes – and they’re everywhere. For that, we can thank one of the most pivotal – and overlooked – artists of the 20th century, wrote Roy Schwartz. Jack Kirby, creator of the 1976 “Eternals” comic that was adapted for the big screen in 2021, was “foundational to the success of the Marvel Cinematic Universe as it currently exists” and his artistic influence “can be found today in virtually all forms of visual media and art, from film to advertising to photography.”

Other times, we want more than a hero. David M. Perry and Matt Gabriele contended that’s what the wildly popular series “Ted Lasso” provides. Rejecting the common critical reception of Jason Sudeikis’s character as a paradigmatic “nice guy,” they wrote: “The show’s tension and success stem not from its oft-touted emphasis on kindness, but from its ability to embody something that in the past would have been called caritas” – a concept of love that is drawn from early Christianity, although it’s not exclusively religious. Caritas – like “Ted Lasso” – “reminds us that there’s a world possible in which people can count on one another.”

Heroes can be unexpected. Sara Stewart wrote that one of the biggest on-screen surprises for her in 2021 was realizing that Nicolas Cage’s character in the movie “Pig” is an everyman. She writes, “We’re all living in a time of unparalleled anxiety and sadness. What better time for a little movie about a man, a swine and the unbearable weight of grief? Are we not all in some way Robin Feld (Cage’s character), struggling out of the wilderness with unkempt beards and dirty faces, squinting at civilization like it’s a memory we’ve long forgotten, trying to get back something invaluable that we’ve lost?”

Koritha Mitchell reminded us that who gets to be the hero is inherently a question of power. Analyzing the response to the Netflix series, “The Chair,” she argued that viewers who criticized this fictional show as an unrealistic portrayal of academe were falling prey to a problem she sees in her classroom: an inability to treat female characters of color as protagonists in their own stories. Jemar Tisby praised “Colin in Black & White,” the docudrama about Colin Kaepernick’s youth and rise to prominence, for showing the world a hero-in-the-making that would have helped his own younger self find peace in his own skin – and still has the capacity to offer that to others seeking “their own ways to become more conscious of their racialized place in the world.”

More insight for your binging pleasure:

Bill Carter for CNN Business Perspectives: Snowy wonderlands, twinkle lights and love against all odds: Time to binge on cheesy Christmas movies

Airielle Lowe: Why Americans are so obsessed with ‘Squid Game’

Peniel E. Joseph: ‘Master of None’ offers a radical new take on Black love

Lindsey Mantoan: ‘The Morning Show’ and the power of a second act

Clay Cane: Billy Porter and ‘Pose’ embody a singular moment in LGBTQ history

Holly Thomas: Paris Hilton’s cooking show is really about something else

Let’s talk about the climate apocalypse

Amid a mélange of weather disasters – hurricanes, wildfires, punishing heat waves in the Pacific Northwest and floods in Asia and Europe – the world community came together, first with a dire report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in August and then at the COP26 conference in Glasgow in November, to bring home the reality of climate change.

John D. Sutter, working with McKenna Ewen, documented how this global crisis is also playing out in the lives of everyday people and asked: “Is anywhere safe from the climate emergency?” They interviewed Americans fleeing climate change on the coasts and explored one Midwest city, Duluth, that is becoming a climate safe haven.

Scholar Britt Wray outlined research showing how the existential threat of climate emergencies has distorted the mental health of young people. One of them told her: “Climate change (has) narrowed my imagination and stolen my future.” Holly Thomas took Richard Branson and the billionaires launching themselves into space to task for … well, a lot of things, but especially for the potential climate impact of their efforts. “Whether the environmental impact of such trips is offset or not – let’s hope they are – this feels like a weird moment for the richest people in the world to direct their outrageous resources toward an endeavor with no immediate benefits to the overwhelming majority of society,” she wrote.

More sharp commentary:

Jamie Beck Alexander: Seeking your climate refuge? Consider this

Kari Nixon: My community is sizzling to a crisp

Vanessa Nakate: You can’t crop an entire continent out of the fight against climate crisis

These women demand change

Gymnasts Simone Biles, Aly Raisman, Maggie Nichols and McKayla Maroney held the nation’s rapt attention with harrowing testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee in September, shining a righteous light on the FBI and revealing an urgent need to do more at all levels of law enforcement to confront the violence perpetrated against women and girls across our society. “The gymnasts’ words were gut-wrenching to hear, both because of the deep suffering they described and because it was clear throughout that these young women, these strong athletes, should never have had to be there in the first place,” asserted Kara Alaimo.

The devastating testimony punctuated a year in which women athletes sought to transform their institutions by demanding change. In the fall, the National Women’s Soccer League was rocked by allegations of sexual coercion and misconduct and a lack of accountability by league officials (some of whom resigned). Former players and current stars alike came forward to speak out, and Amy Bass insisted that to have their backs, the “call to protect players, to protect women and girls, cannot just happen among colleagues and peers and it has to be more than words. The structures that govern our world, perhaps especially our working world (and professional athletes are, indeed, workers) – from sporting federations to corporations, at institutions of higher education and on shop floors – need to strike it all down and rebuild in a way that ensures those in charge are actually practicing protection for those on the field.”

Stars like Biles and Naomi Osaka also sparked international dialogue about the need to protect athletes’ mental health as much as their physical well-being. Former elite athlete Mia Ives-Rublee described her own struggle with mental health pressures and microaggressions as a woman of color, writing that it’s “time to listen to the athletes emerging as leaders in their own right here.”

The call for women’s autonomy wasn’t limited to the world of sports. Perhaps the most visible manifestation came with the zenith of the #FreeBritney movement: documentaries, hearings and protests culminated in Spears’ release from a conservatorship that lasted more than a decade. According to Nicole Hemmer, “The attention being paid to the Spears case is happening at a crucial moment: seeing a woman being freed from the control of her father, and slowly regaining full autonomy over her own life and body, is a reminder of why all women deserve the right to control their lives as well.”

Don’t miss:

Marcie Bianco: Britney fans angry at Justin Timberlake have a point

Rafia Zakaria: Rachel Nichols’ words confirm the fears faced by women of color

Jane Greenway Carr: These are the women who crushed the Caliphate

A haunted America

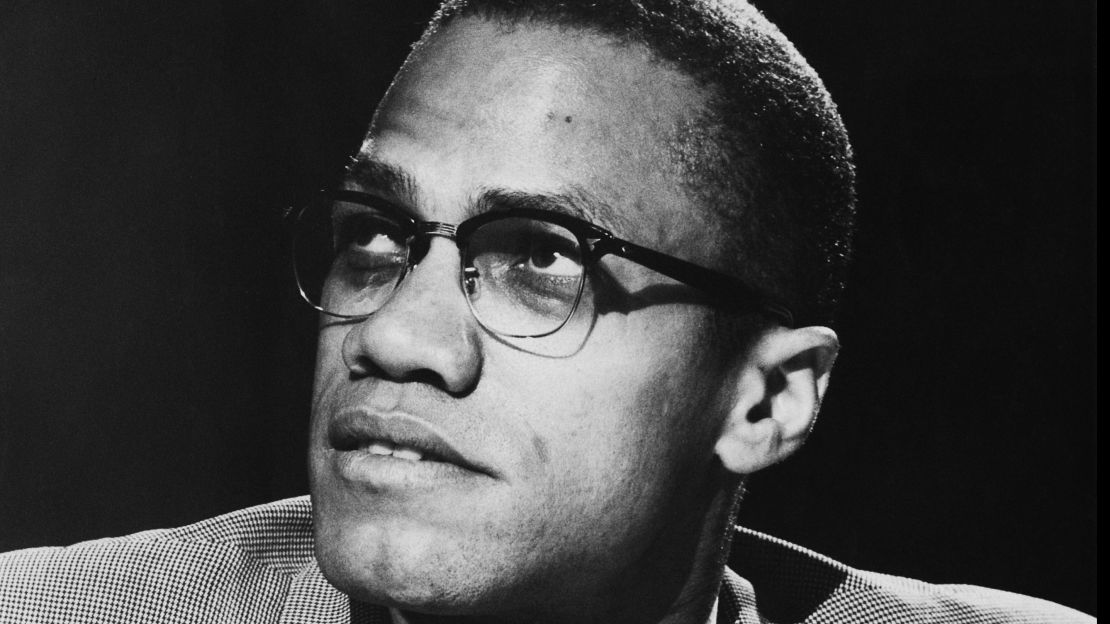

Building on decades of work by scholars, activists and community members, the 2019 Netflix documentary series, “Who Killed Malcolm X?” helped prompt the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office to reopen an investigation into the 1965 assassination. In November, Muhammad A. Aziz and Khalil Islam (formerly Norman 3X Butler and Thomas 15X Johnson) – who each spent more than 20 years in prison – were exonerated after the investigation found the FBI and New York Police Department withheld evidence that could have been pivotal. Peniel E. Joseph (who was an on-air historian for “Who Killed Malcolm X?”) reflected, “These new revelations about the corrupt investigation into his death helps us to better understand why, in life, Malcolm emerged as a relentless critic of the justice system’s mistreatment of Black America … (His) legacy continues to haunt America’s criminal justice system in ways that are both sobering and hopeful.”

Gene Seymour commented on other hauntings, noting that on “April 20, the same day that a Minneapolis jury found former police officer Derek Chauvin guilty of murdering George Floyd almost a year before, the Library of America released a long-lost novel that began with White policemen beating and torturing an innocent Black man into confessing to a double murder he didn’t commit.” “The Man Who Lived Underground,” by “Native Son” author Richard Wright, was unpublished for 80 years. But the novel, according to Seymour, “triggers instantly recognizable parallels … (but) however much the criminal justice system is reformed in the wake of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other casualties of excessive policing, it’s really the renewed insistence on humanity prompted by their killings that Wright anticipates with his novel.”

The power of remembrance – and reparation

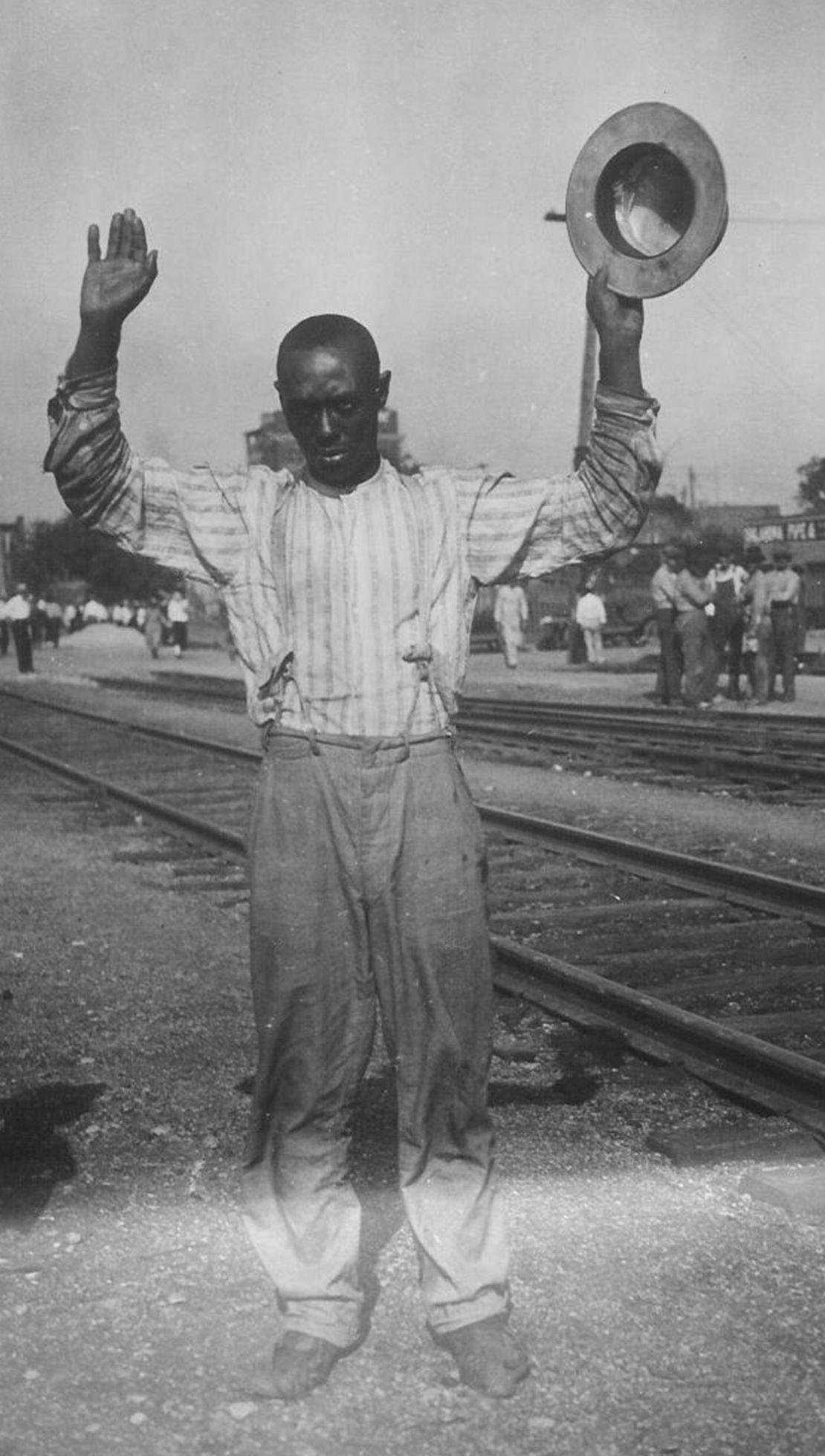

Just days after the first anniversary of George Floyd’s murder, the country observed another sobering milestone: the 100th anniversary of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, in which the city’s Greenwood neighborhood, known as Black Wall Street, was largely destroyed by White mobs that killed many Black residents. “In 1921, the city of Tulsa and the state of Oklahoma failed to deliver justice to the victims and survivors of America’s worst race massacre,” said Karlos K. Hill, who spoke out on behalf of those seeking reparations for the massacre: “This occasion offers another opportunity to restore what the remaining survivors and the members of the Greenwood community deserve: justice.”

“God loves Tulsa,” Robert Turner, pastor of Vernon AME Church – one of the few structures to survive, even partially, the destruction, and which remains a cornerstone of the neighborhood – told me. “I would say that this city is not unusual. That we all have Tulsas in our states … and justice for the most part has not been done. That’s the scary part about Tulsa, it is not unusual.”

Anneliese M. Bruner, whose great-grandmother Mary E. Parrish published her eyewitness account of the massacre, recalled that Parrish “admonished the nation to awake to the factors that feed state-sanctioned violence and provided a model for capturing and preserving the truth. She knew, as did the other survivors of the massacre: Our democracy depends on it.”

Looking forward by looking back:

Keri Leigh Merritt: Jackson water crisis shows Nina Simone is still right about Mississippi

Elizabeth Alexander: The big problem with America’s monuments

W. Ralph Eubanks: This is what will finally transform the South

Reece Jones: How the Statue of Liberty became a symbol for a national myth

2021 in the first person

These personal stories of how the news shapes real life and vice versa really stood out:

Michelle Duster: My great-grandmother exposed lynchings. This is what she would say about the Capitol riot

Sandra Garza: I can’t forgive the people who won’t admit my partner, Brian Sicknick, was a hero

Keith Magee: A year after George Floyd: A letter to my Black son

Nina Trieu Tarnay: We left my little brother and a world behind us when we escaped Vietnam by boat

Dalia Hatuqa: My journey through fertility treatments in the pandemic

Morgan Stephens: Eight months of long Covid brought me to the brink

Anne Lagamayo: A brain injury turned my life upside down, and I’m still finding my way forward

Dr. Syra Madad: How my kids feel about getting the Covid-19 vaccine

Kelly McHugh-Stewart: Gold Star daughter: 20 years after 9/11, where do we go from here?

Imara Jones: My life growing up Black and trans in 1980s Atlanta

Claudia Dreifus: I almost died trying to get an abortion. I’m terrified my students could face a similar fate

What comes next?

The pulse of 2021 was a question: What comes next? We reached new thresholds of vaccination and saw rollbacks of safety measures, but we also confronted more surges and new variants, including Delta and Omicron. And yet, wrote Nicole Hemmer, Americans are primed for “a new Roaring ’20s” – an echo of the decade when the rise of cities and the crackling demand for new life after World War I and the 1918 flu pandemic combined to transform culture. We hunger for the same aliveness and creativity evident in the Jazz Age and the Harlem Renaissance, she observed, but we must guard against the surges of xenophobia and hate that previewed the total economic collapse to come during the Great Depression.

“That fusion of culture and politics is precisely what we should have our eyes open for,” Hemmer affirmed. “To combat both a politics of exclusion and an economics of inequality, we will have to find ways to fold those into the cultural vibrancy of the coming decade.”

Tess Taylor drew parallels between Dorothea Lange’s photographs of the Great Depression and our own uncertain moment. “There is something in Lange’s photographic gaze that insists upon our linked fates and our common dignity, and also gives us the chance to grapple and reckon with our national scars,” Taylor observed. Taylor urged people to use this moment to invest in art’s restorative power as a public good: “What should we make? What could we? What might it be to undertake that daring? In this moment, it feels once again urgent that we look.”

We wish you joy and health this holiday season. Thank you for sharing another year with us.