There’s a word in Norwegian for when the horizon vanishes, an illusion on a certain kind of day where the land or sea appear to melt into the sky.

It’s hildring, and it has special significance for Craig Dykers and Kjetil Traedal Thorsen, co-founders of the design practice Snøhetta, which claims to break down divides between architecture, landscape architecture, product design and graphics.

Since last May, Norway’s banknotes have borne one of Snøhetta’s visions of the hildring: a pixelated representation of the horizon printed on the back of 100 and 200 krone bills. But its importance to the designers becomes clearer during the firm’s regular pilgrimage up the highest hilltop in central Norway’s Dovrefjell range, Snøhetta, the mountain from which the firm gets its name.

3D landscape

As the whole staff finds its way across rock and through fog, toward the snow-capped mountain peak, the horizon provides a new guide to understanding our place in the world, says Thorsen, the Norwegian founding partner.

“One way to know your location is to look at the map. But another one is to look at contour lines and recognize the ‘three-dimensionality’ of the landscape, or even to look at the horizon,” Thorsen said in a phone interview, adding that, to the observer’s eye, this line moves and warps as you approach the mountaintop.

Snøhetta has made its name shuffling people, buildings, animals and the natural environment in playful new arrangements. Like the firm’s celebrated Norwegian National Opera and Ballet house in Oslo, designed to allow visitors to climb up its exterior and explore its jagged, icy roof. Or the sloping concrete slab in Lindesnes, southern Norway, that invites visitors to climb down into a long void that will become Europe’s first underwater restaurant when it opens next year.

Dykers, the American co-principal, says that the pair are not especially interested in any formal theory “of what objects should look like”. Instead, their designs aim to transport you from one place to another, redefining a person’s relations to their environment and creating new ways of interacting with the world.

“Essentially, hildring refers to a kind of hallucination,” says Dykers. “You understand that landscape, the things we walk on, and the sky, the thing we walk through, are very closely connected.

A house for life, art and eternity

Starting out as an informal group of designers who met above a beer hall in Oslo, Snøhetta took off in 1989, when the firm won the competition to build a new Alexandria Library in Egypt, and now employs 200 staff in eight offices from San Francisco to Adelaide, designing the World Trade Center Memorial and the popular extension of San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art.

But a smaller building could be their most maverick design: a private residence, designed for artist Bjarne Melgaard just outside the Norwegian capital, on a plot of land next door to the estate of Edvard Munch, the expressionist painter of “The Scream.”

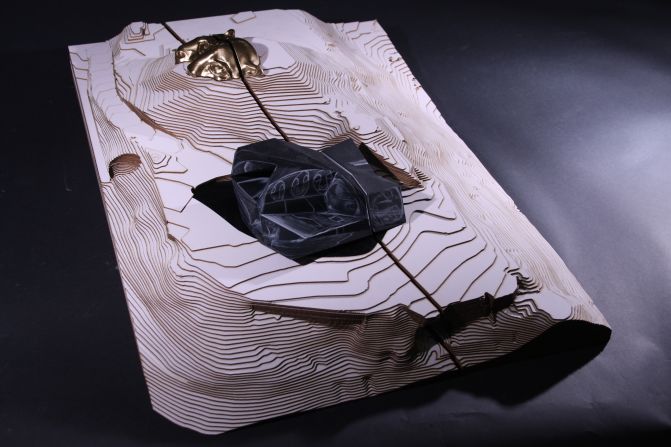

Plans for a floating, angular UFO-like structure has faced stark opposition from residents and supporters of the artist community that now lives on Munch’s land. But the project represents something truly exciting, argues Thorsen: a new way of living and “the transition of a fantasy into some sort of reality.”

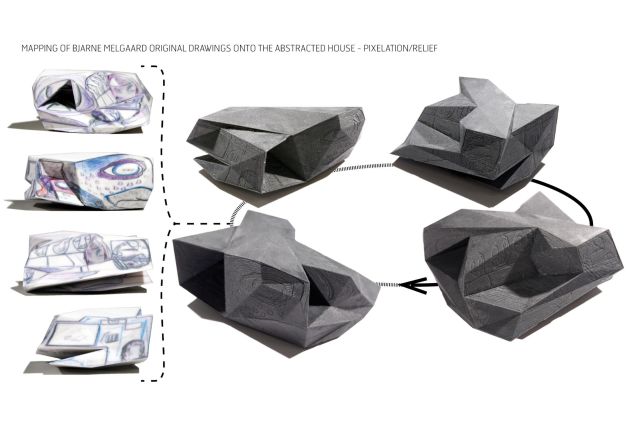

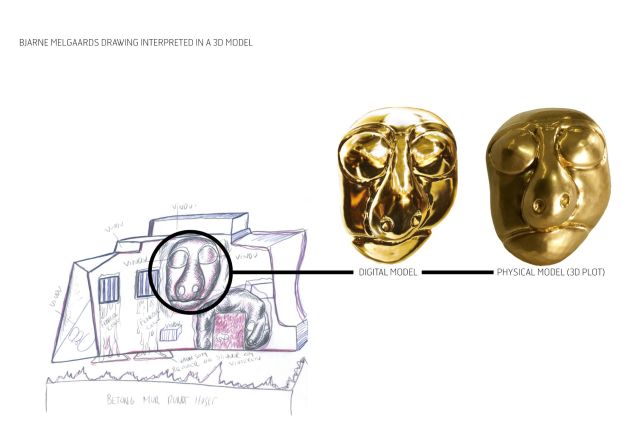

The seven-year design process has involved working with controversial artist Melgaard to transform his paintings and sculptures into a vision for a new kind of house, envisaged to ignite creativity.

Human habitat

This burnt oak structure, resembling a jagged shard of onyx, appears to hover over a pool of water, propped up by white sculptures based on Melgaard’s anthropomorphic animal motifs. Inside, the architects suggest rooms will double-up functions that are usually divided: combining in one space a swimming pool and dining room, or a workspace and spa. “It’s really breaking all the conditions that you would have for a normal living quarter. But it’s still a habitat,” says Thorsen.

Snohetta bjarne melgaard sketches

The house – known as the “House to Die in,” for the owner’s desire to be buried on-site – is defined by its refreshingly honest way of presenting the life of its artist-occupier, the architects say.

Death remains something we tend to push to the side as a “taboo”, says Dykers.

“But that’s not necessarily healthy as a society,” he adds. “Being open and honest about the things we require as human beings is important to understand, and if we can design places – architectures, landscapes, things – that respond to these most primitive components of life, we’ll feel more natural in our skin and theoretically more natural with each other.”

Thorsen continues: “It would be like if you’d have a habitat for a bee, it would look different from the habitat of a human. This is the habitat of an artist.”

Better ‘zoos’

The Norwegian’s comment might be strange, had Snøhetta not already built a home for bees: a 2014 project for the roof of an Oslo food court. That came amid projects for reindeer and musk ox, and the underwater restaurant, which doubles as a research environment for marine animals.

The experience of working with 80,000 clients who can’t talk back – the bees – has taught them to be more understanding, Dykers says, half-joking.

He says humans are not so different from their animal relations: just as captive polar bears can live better, healthier, more fulfilled, and longer lives if their zoo enclosures are better designed for their needs, architecture allows humans to build betters “zoos” for themselves, in our cities, buildings, and parks.

The pair say the experience of connecting with their habitat is what brings them back to the mountain hike: “In the end, it’s really putting yourself out of the everyday situation, in order for you to discover new things in yourself, by changing your surroundings, by changing the things that you’re talking about to others,” says Thorsen.

Returning to the drawing board, the experience stays with you, Dykers adds. “You may not be climbing a mountain when you’re going to work every day, but your manner of thinking about what you do can be more explorational.”