In Japan, the term “mottainai” – loosely translated to “what a waste” – has deep roots. Originating from a Buddhist belief that every object has intrinsic value and should be utilized for its full life cycle, the credo has been threaded throughout national culture for centuries.

“Mottainai and handmade culture is everywhere in Japan,” said Kaoru Imajo, director of Japan Fashion Week Organization, said in an email. Sake lees (the residual yeast left over from the fermentation process), he points out, has long been used as a cooking ingredient, and discarded orange peels have been reduced to fibers and turned into paper. Brands like Nisai, in their Autumn-Winter 2021 collection shown at Tokyo’s Rakuten Fashion Week (pictured above), upcycle used clothing to design “one-of-a-kind” looks. Then there’s the case of boro textiles – fabrics that are often worn out, but then repurposed, patched together to create new garments.

“We have been fixing old carpets, clothes and fabric so we can use (them) as long as we could,” he said. “Now, boro textiles are traded very expensively and known as a ‘Japanese vintage fabric.’”

Today, a number of Japanese fashion labels are channeling these traditional ideas in the name of sustainability, embracing centuries-old garment production techniques and pioneering new technology to reduce waste and lessen environmental harm throughout the production process.

Innovation from nature

At Shohei, founded by creative director Lisa Pek and CFO Shohei Yamamoto in 2016, sustainable decision-making starts with the dyeing process. Pek says the brand, which operates out of Japan and Austria, has been working with a Kyoto-based artisan to procure textiles dyed using traditional kakishibu methods.

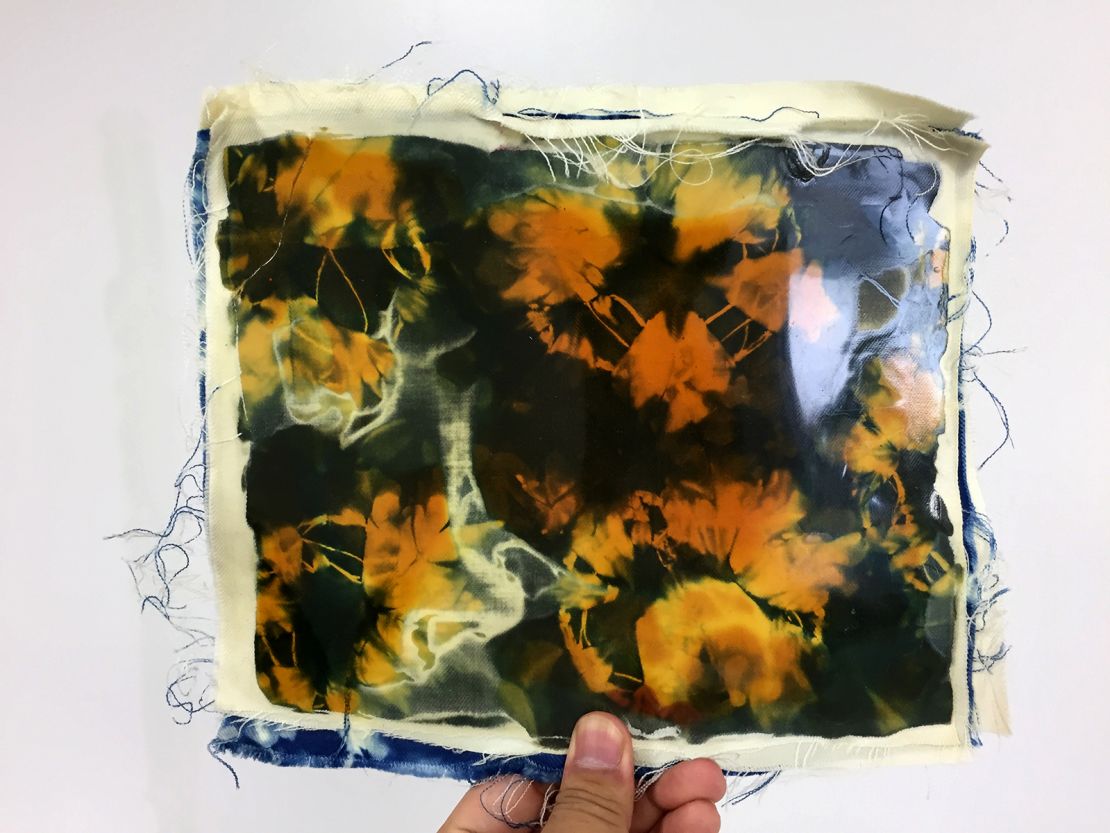

During the kakishibu dyeing process, textiles are immersed in the fermented juice of unripe persimmon fruit – an alternative to popular synthetic dyes, which can be damaging to soil and waterways. After the dyeing process, the fabric is tanned in the sun, creating orange hues. The kakishibu dyeing process also creates a water-resistant effect when oxidized in the air, and provides antibacterial properties. “This is something you might find in a tech fabric,” Pek explained in a video call, “but it’s already there in nature.”

Shohei also sources fabric dyed using shibori – a hand-dyeing technique that dates back to the eighth century – from a family-run business in Nagoya. Like kakishibu, shibori uses natural dyes (typically derived from indigo) and is less harmful to the environment than its synthetic counterparts.

In a similar spirit of eco-friendly production, Japanese designer Hiroaki Tanaka, founder of Studio Membrane, has been working with biodegradable protein resins derived from wool – the basis for “The Claws of Clothes,” a collection of avant garde, architectural womenswear unveiled at the 2018 Eco Fashion Week Australia in Perth. Created in collaboration with Shinji Hirai, a professor at the department of sciences and informatics at Hokkaido’s Muroran Institute of Technology, Tanaka likens the protein resin’s texture to a human fingernail, and its durable texture to plastic.

“I wanted to make totally biodegradable clothes,” Tanaka said over Zoom, through a translator. “Because it’s just made of wool, it’s very (ecologically friendly).”

However, Tanaka admits that his protein resin is better suited to wearable art than everyday clothing. When the resin is wet it reverts to its usual wool form, and loses its structure. However, since wool is biodegradable, he believes the material could be used to replace certain disposable items, such as diapers, that are currently filling landfills.

Using tech to combat waste

As fabric choices are integral to sustainable fashion, new technology and machinery is also at the forefront of this environmental movement, decreasing the amount of fabric wasted during pattern-making, sampling and sewing.

In this arena, Japanese manufacturer Shima Seiki has set the standard with its computerized Wholegarment knitting machines. Unlike the traditional way of producing knitwear, where individual pieces are knitted then sewn together, Wholegarment items are seamlessly knitted in their entirety in a singular piece.

According to Masaki Karasuno, a Shima Seiki spokesperson, up to 30% of fabric is wasted in standard production, when individual pieces of pattern are cut from bolts of fabric before being sewn together. “All of that is eliminated when an entire garment can be knitted in one piece directly off the machine,” he said in a phone interview.

Wholegarment’s machinery gives brands the option to produce clothing on demand – another way to reduce industry waste. “Mass producing garments based on projected demand tends to overshoot actual demand (and is the reason) why there’s a lot of overstock… which results in waste,” Karasuno explained. “Wholegarment can produce the number of garments that are required, when they are required.”

In 2016, Fast Retailing Co., the parent company to fast fashion giant Uniqlo, started a strategic partnership with Shima Seiki called Innovation Factory, where they produce a variety of Wholegarment knits for the Uniqlo brand. Since then, Italian fashion label Max Mara and American clothing brand Paul Stuart have also turned to Shima Seiki’s Wholegarment technology.

Shima Seiki also offers a virtual sampling platform which provides realistic renderings of individual garments – alternatives to the physical samples that are produced as a collection is developed. Often, sampling is an iterative process, with factories sending new, tweaked versions of a garment until the designer is content with the final product. While the process is helpful for designers, allowing them to adjust for factors like fit, placement and quality, these prototypes often end up landfills.

“Each of those samples that gets wasted requires time, cost, material and energy to produce … and all of those are just thrown away,” Karasuno said.

Shohei has been partnering with No Form, a digital design studio, to produce realistic 3D images of some of their garments using tech similar to Shima Seiki’s virtual sampling platform. These renderings can be used in their online store in place of photos of samples. “It’s the same as when you think about architecture, where you create a model… before building it,” Pek said. “It’s also another way to be environmentally friendly and save costs.”

Christina Dean, the founder and board chair of Redress, an environmental charity that aims to reduce textile waste, believes the steps taken by Japan’s fashion industry is setting a positive example for a healthier fashion ecosystem internationally.

“I think it’s very interesting how islands deal with innovation. If you have a country that can’t have endless landfills, and you can’t ship all your waste and dump it somewhere else… it drives innovation,” she said in a phone interview.

“When you go to Japan it’s a beautiful, considered, minimalist, cultured society, and if you couple their traditional past with the fact that they are very high tech, the textile industry in Japan is a champion in terms of technology.”