Editor’s Note: Artist Takashi Murakami is CNN Style’s latest guest editor. He has commissioned a series of features on identity.

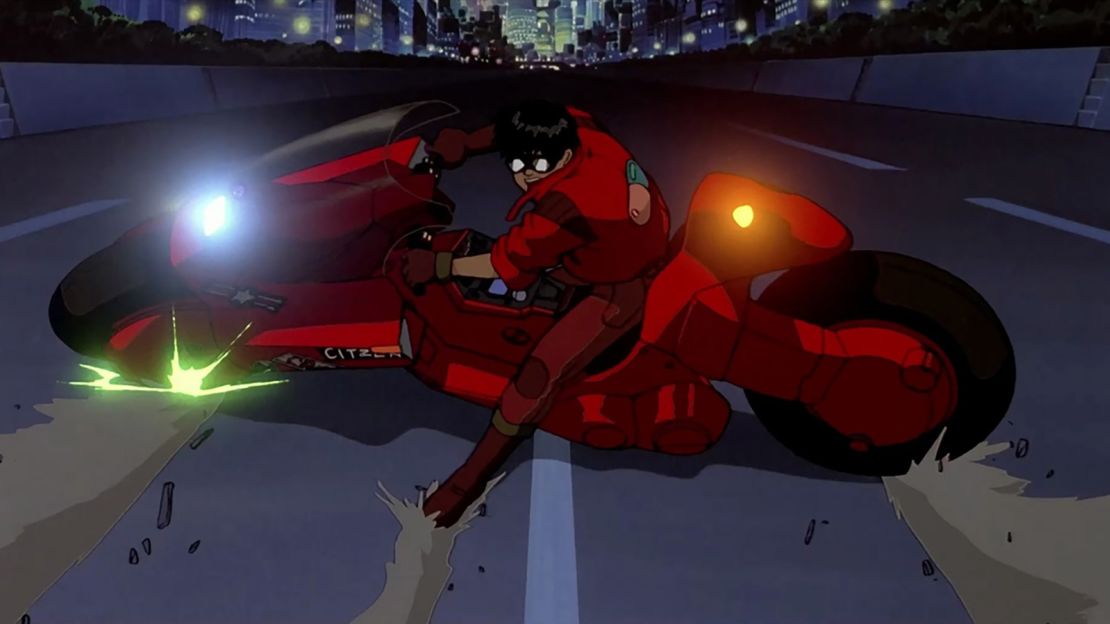

A biker gang slices through Tokyo’s neon-soaked night. The riders hit the brakes next to a giant, black crater created by an atomic blast. It’s so enormous that it bursts beyond the comic strip panels and seeps across the whole page.

This is the opening of “Akira,” a popular science-fiction manga (Japanese comic or graphic novel) created in 1982 by Japanese artist Katsuhiro Otomo, whose work soon spread to a small core of fans in the US.

“Americans had never seen anything like this before,” said Susan Napier, a professor of Japanese studies at Tufts University, in a phone interview. “‘Akira’ was an incredible post-apocalyptic story that had psychological depth and the visuals to match. It was pushing boundaries in a way US comics at the time were not.”

Compared to DC Comics and Marvel, “Akira” felt subversive and different. The story follows biker gang leader Shotaro Kaneda as he battles to save his friend from a secret government program that conducts tests on psychic children.

In 1988, Otomo released “Akira” as an anime, a film so detailed and intricate that it took animators years to hand-paint each of the single shots used to bring the story to life. The film is now widely considered a cult classic that expanded anime’s reach in the US and Europe.

Touching on themes as disparate as sex, death, science fiction and romance, manga and anime catered to all ages and tastes. Commercial hits like “Pokémon” and “Dragon Ball Z,” meanwhile, projected a new image of Japan to the world.

“The image of Japan in the West (in the 1980s and early 1990s) was composed of two extremes: that of the orientalized, feudal Japan depicted in samurai films with ninjas and swordfights, and that of hypermodern Japan where economic animals are crammed into trains and pump Walkman and Toyota to the world,” said Kaichiro Morikawa, an anime expert at Tokyo’s Meiji University, in a phone interview.

“The popularity of Japanese manga, anime and games have injected the world with a more human and relatable image of Japan and the Japanese.”

After seven years of consecutive growth, the anime industry set a new sales record in 2017 of ¥2.15 trillion ($19.8 billion), driven largely by demand from overseas. Exports of anime series and films have tripled since 2014 – aided in part by sales to streaming giants such as Netflix and Amazon – and so far show no signs of slowing.

A picture-centric country

Japan is a country that possesses a rich, detail-oriented visual tradition.

Famous woodblock printer Katsushika Hokusai was one of the earliest artists to use the term manga (in his collection “Hokusai Manga,” first published in 1814) in reference to sketches depicting both the supernatural and the mundane.” Manga as we know it today emerged in the early 20th century in serialized cartoon strips in Japanese magazines and newspapers.

Anime came about in the early 1900s when Japanese artists like Oten Shimokawa began experimenting through trial and error to create short animated films. But back then, animations were costly to produce and works from Japan were overshadowed by Disney’s success.

During World War II, the genre expanded as Japan’s military government ordered animators to create propaganda films to influence the masses. Following Japan’s defeat in the war, the manga and anime industries shifted gears again.

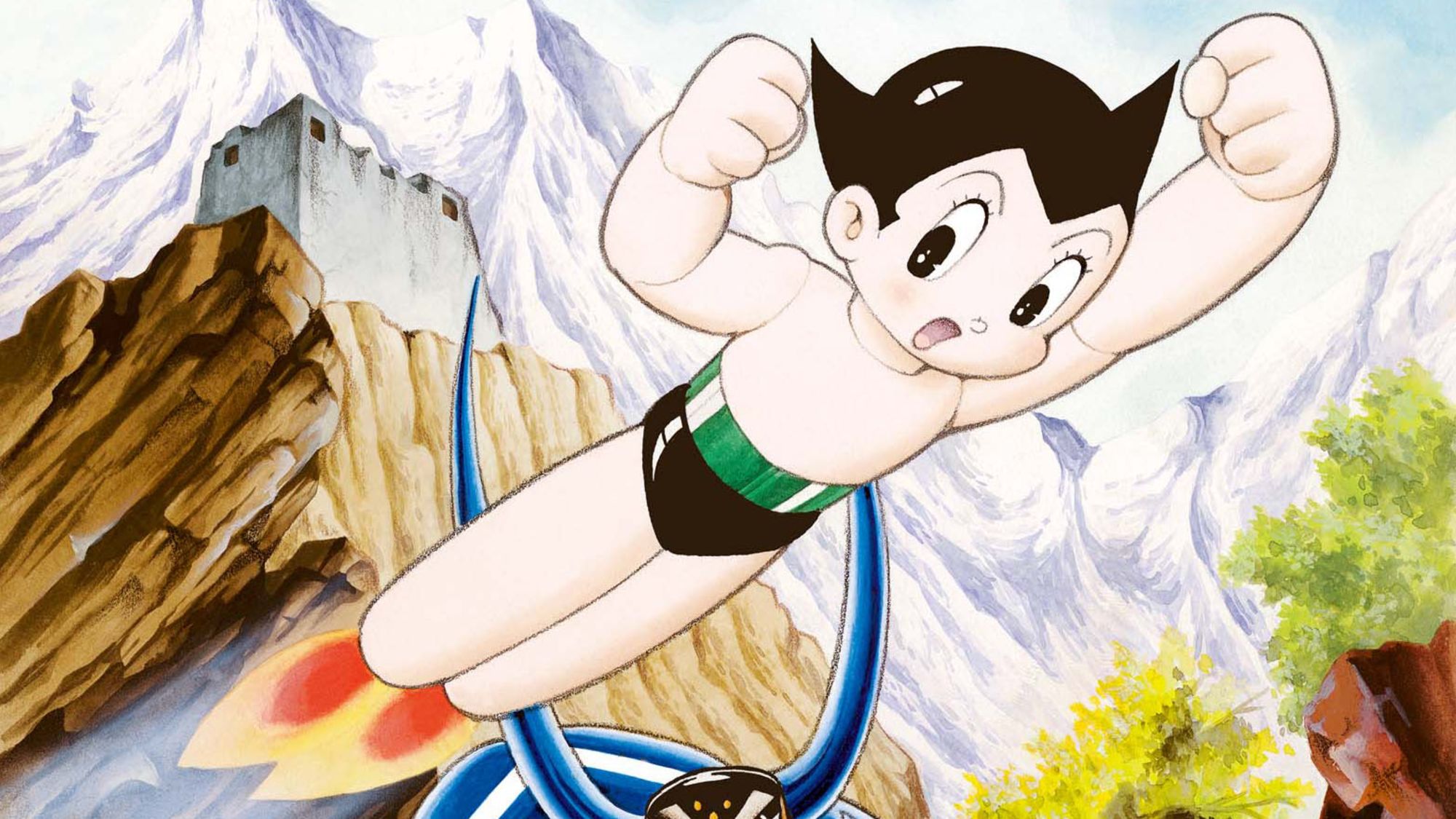

In 1952, artist Osamu Tezuka – who grew up watching early Disney animations – released “Astro Boy,” a manga about a peace-loving robot boy with X-ray vision and super strengths.

Interest in “Astro Boy” was so high it earned Tezuka the title “father of manga” and paved the way for an anime film about the robotic boy in 1963.

The strengths of Japan’s animation industry boil down to the overlap between manga and anime, according to Ian Condry, the author of “Anime: Soul of Japan.”

“Creators used comics as a testing ground for their stories and characters. That’s often been the secret of anime’s success,” said Condry in a phone interview.

Tezuka’s rise paralleled the Japanese animation industry’s expansion abroad.

In the 1950s, Toei Animation studio (where Tezuka had worked before establishing a rival company, Mushi Productions, in 1961), set its sights on becoming the “Disney of the East” and started exporting animation films to America.

“Such export enthusiasm in its early days was based on the worldwide success of Disney’s animation films, as well as upon the assumption that animated films would have a better chance of succeeding in the West than live-action films featuring Asian actors,” said Morikawa.

But while “Astro Boy” sparked a mid-century anime boom in Japan, it would take a few more decades for the genre to sweep America.

Grassroots phenomenon

In the early 1980s, it was largely American and European children from military and expat business families based in Japan who circulated boot-legged videotapes of anime to their peers back home, according to Mizuko Ito, the editor of the “Fandom Unbound: Otaku Culture in a Connected World.”

Futuristic titles such as “Cowboy Bebop” and “One Punch Man” also captured the imagination of tech-savvy foreigners involved in the burgeoning computer and internet industries. Word spread as they translated Japan’s anime and circulated pirated copies online.

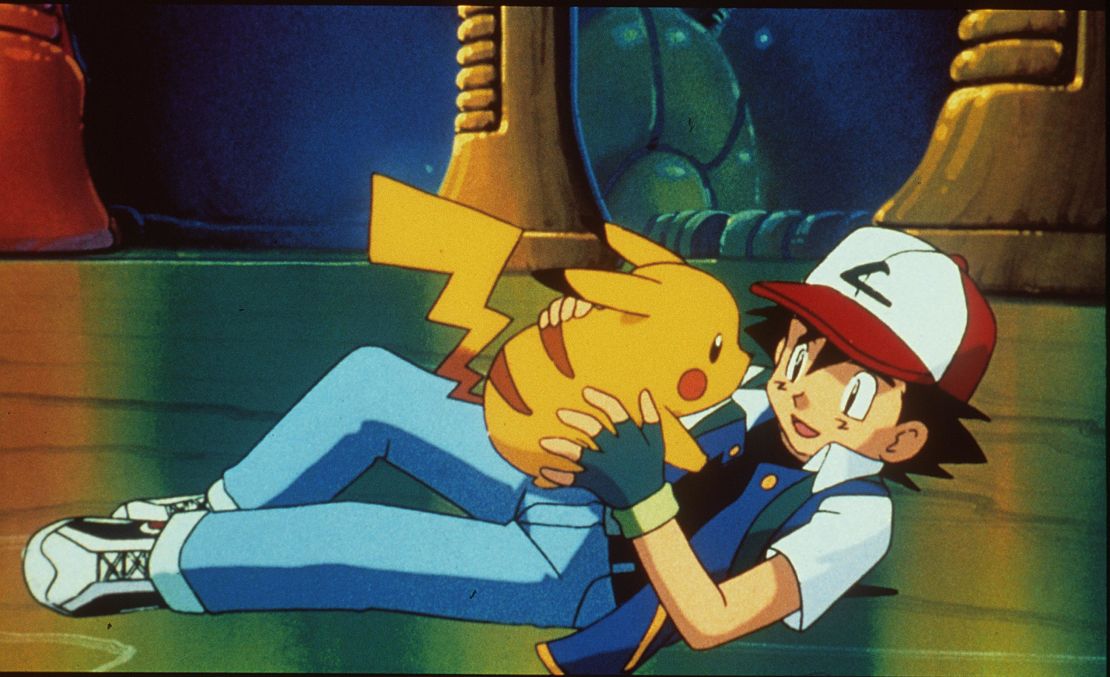

“Unlike so many other cultural fads (like Pokémon), anime was not pushed by a giant corporation,” said Napier. “It was popular culture coming out under the radar through word of mouth.”

As Japan’s economy flourished to become the world’s second largest in the 1980s, Japanese language classes became available in the West and anime and manga entered the classroom as educational tools.

At the same time, “otaku” (geek) culture was becoming more mainstream in Japan, and fans with an internet connection helped to spread it worldwide.

Young Americans were searching for cultural products offering new perspectives and, to them, Japan appeared to be a place as exciting as “Akira” – its cyberpunk landscape and controversial plot offering a portal into a different aesthetic and psychological universe.

“Japanese culture was confronting darker, exciting themes in a way that the US and Europe and seemed slower at adopting,” said Napier. “(Anime) became a way of filling an intellectual void in the West.”

Shifting attitudes

In the late 1990s, a Japanese consortium between Nintendo, Game Freak and Creatures pushed Pokémon, a video game series featuring hundreds of fictional cartoon-like creatures, into the mainstream. It ushered in a bigger anime wave outside Japan.

Pokémon fever swept the globe, triggering a franchise blitz of anime, plushies and trading cards as the bubblegum-yellow Pikachu became a staple on American television sets. Nintendo sold more than 31 million copies of the 1996 game “Pokémon Red/Green/Blue,” and the television series has aired in more than 100 countries.

The world’s interest in anime even changed attitudes towards the genre at home, according to Takako Masumi, a curator at The National Art Center, Tokyo.

Masumi compares the growing popularity of anime within Japan to the transition of ukiyo-e (woodblock art) from a low to high art form. Ukiyo-e was initially used to wrap ceramics to prevent them from breaking when they were exported abroad towards the end of the 19th century.

At first, the decorated paper was considered nothing more than paper waste. But Japanese attitudes towards ukiyo-e shifted as people abroad bought the ceramics and started collecting and valuing the beautiful pictures used as wrapping. They reevaluated it as art.

Anime – which stems from such visual culture – said Masumi, underwent a similar transition. Initially sold cheaply abroad by animation studios, it spread quietly and quickly. “It was cheap to sell but as the contents was quite attractive, it captured children’s hearts,” said Masumi.

Eventually, even the Japanese government saw an opportunity.

Shaping Japan’s image

After Japan’s once-miraculous economy went bust in the 1990s, the nation sought to rebrand itself from a global business superpower to an exporter of a unique artistic culture.

The country pivoted from mass-marketing high-technology offerings to spreading the word on everything from Hello Kitty to sushi.

In 1997, Japan’s Agency of Cultural Affairs started supporting exhibitions on manga, anime, video games and media art.

American journalist Douglas McGray captured that shift in his 2002 Foreign Policy essay, where he coined the term Japan’s “gross national cool.” McGray described it as an “idea, a reminder that commercial trends and products, and a country’s knack for spawning them, can serve political and economic ends.”

Soft power – a way for one country to influence public and international views and values – had become the order of the day. But by then, anime culture had already taken on a life of its own.

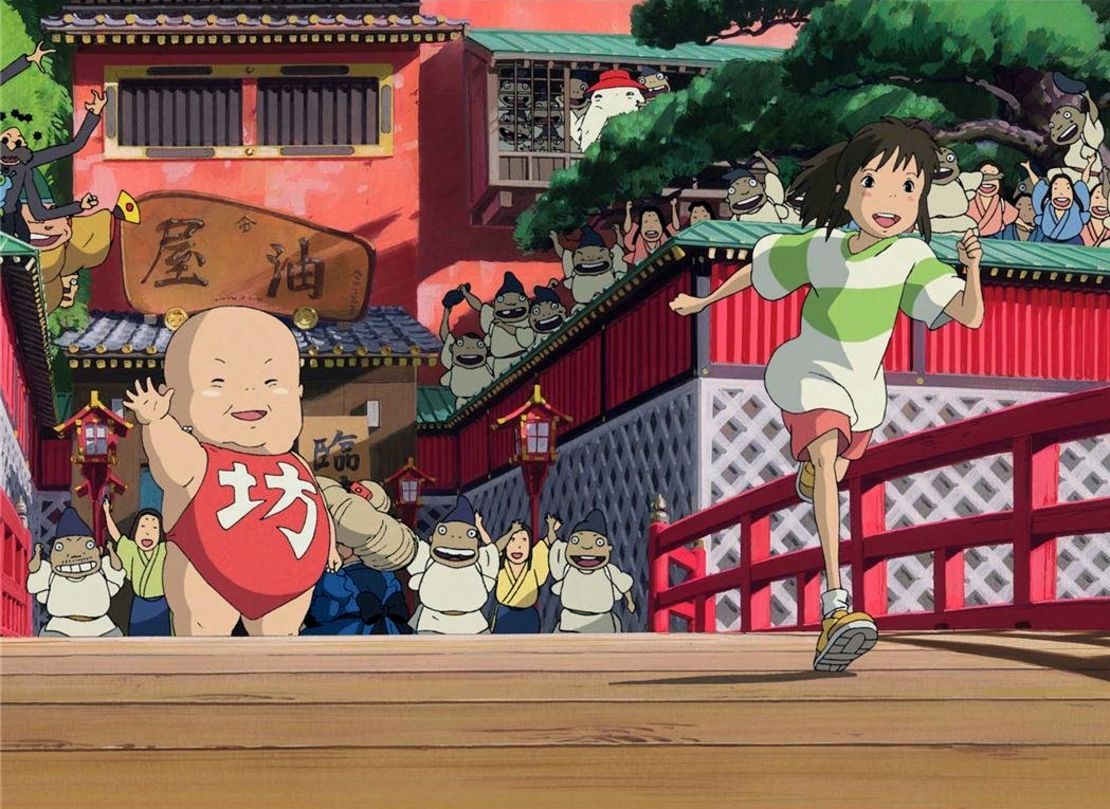

Viewership had been surging, as films like Studio Ghibli’s “Spirited Away,” directed by the studio’s co-founder Hayao Miyazaki, entranced the world in 2001.

The film has generated $277 million at the box office, and was the highest-ranking anime film ever until “Your Name” by Makoto Shinkai knocked it into second place in 2016 with global takings of $357 million.

Named a “Living National Treasure,” a government accolade recognizing individuals who help preserve the country’s culture, Miyazaki drew on Japanese traditions and reverence for nature, but touched a universal human nerve.

Anime has a following similar to rock ‘n’ roll music and Hollywood cinema, according to Doryun Chong, the deputy director and chief curator of M+ museum in Hong Kong. “It’s arguably one of the first as well as most extensive globalized cultures,” he said on the phone.

And as anime continues to make inroads abroad, the industry may no longer belong just to the Japanese.

“I think we could see further diversification of the medium, outlets and centers of production outside of Japan,” said Chong. “Anime posses an incredible narrative imagination – that’s been the crux of the global success.”