Editor’s Note: Amanda Levete is a RIBA Stirling Prize-winning architect and founding principal of AL_A, an international award-winning design and architecture studio based in London. For her September 2017 CNN Style guest editorship, she explored the theme of thresholds – both real and imagined – as applied in architecture and far beyond.

David Miliband is president of the International Rescue Committee. He is a former British Member of Parliament and a former British foreign secretary. The opinions in this article belong to the author.

The world is increasingly connected and in some spheres borderless. Architects and urban planners work to soften the thresholds between public and private spaces in cities. Digitization blurs the lines between real life and virtual life every day. Technological advance transforms thresholds in the workplace every year.

Today’s global challenge is to harness the potential of this change and defy its dangers. Nowhere is this more true than when it comes to the movement of people.

The upside is opportunity to travel, study, work, spurred by more and better flow of information. The downside is the return of ugly nativism.

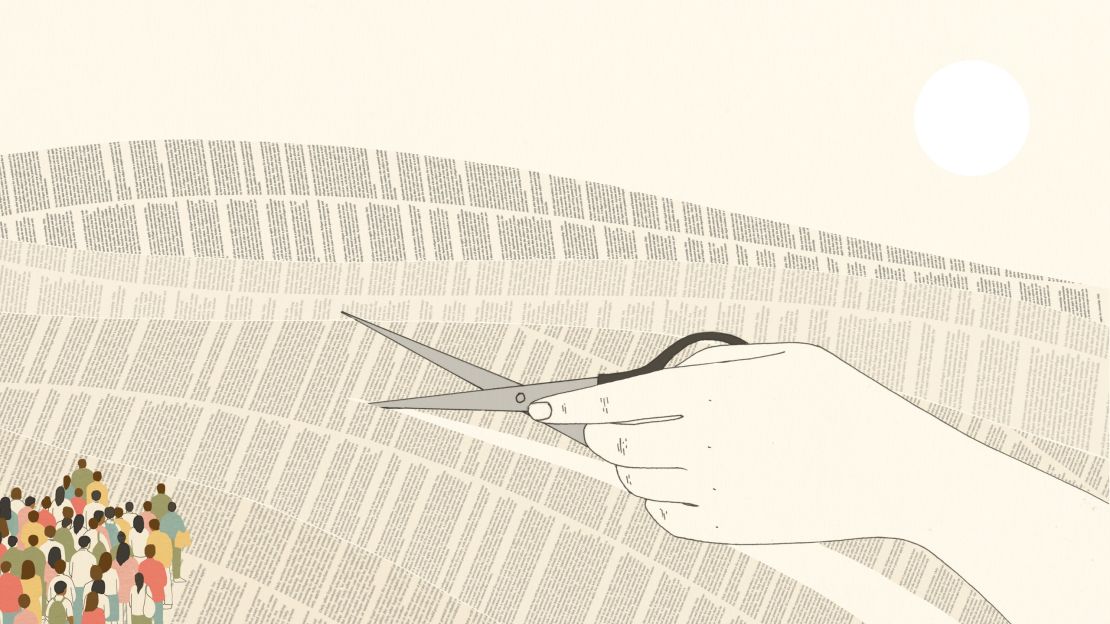

The scale of people movement, forced and voluntary, is unprecedented. In 2016, the Pew Research Center found that 244 million people had migrated across borders, but most concerning are the estimated 22.5 million the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) says have been displaced across borders by conflict and persecution as refugees.

The threshold between foreign and domestic policy is being broken. Many problems need a foreign and a domestic component: environment, public health, security. That is true of policy for refugees.

Refugees are often the victims of failures in peacemaking and peacekeeping. They require states to live up to international commitments to provide safe haven.

And when they arrive in large numbers – more than a million refugees have arrived in Uganda from South Sudan in the last year, and Germany has processed more than a million since 2015 – they need to be integrated in local labor markets, schools, housing.

Some thresholds continue to matter. One is the definition of a refugee. Drafted in a different world in 1951, the UN Refugee Convention spoke to a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.”

These five reasons for flight continue to provide the foundation of international law today, with 145 states having ratified the Convention.

This leaves all sorts of gray areas. Are people fleeing hunger, forced to leave their country to live, fleeing persecution? Not really, but it is not voluntary either. Are people crossing borders because of climate change refugees? It is hard to say: climate is more of a flight multiplier than a single source of movement.

Despite the gray areas, the integrity of refugee status matters. For centuries refugees were not counted and did not count. It took the 40 million refugees stranded by World War II to prompt the establishment of rights for these victims of war. Trash the protections for refugees and we trash our own history of global leadership.

The family bombed from their home in Aleppo, the girls facing violence for seeking education in north-eastern Nigeria, the religious minority persecuted for their beliefs and the political dissident in fear of his or her life face a different set of incentives from the student seeking better economic opportunity or the family opting to join cousins in a new country to improve their life-chances. They should have greater rights and protections because they face far graver threats to life and limb. Gray areas should not be an excuse to dilute rights.

There is a practical reason too. It would be impossible to get the 193 nations in the United Nations to agree on a new refugee law. We need to make the current one work much better.

Per the UNHCR, half of refugee children of primary school age are not in school. Last year, a Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan report revealed that the vast majority of Syrian refugees are living in poverty. And the gap between need and support is growing.

The myths abound: That refugees are in camps (more than 60% are in urban areas); that refugees are queueing up to get into rich countries (84% are in developing regions); that displacement is short term (the average refugee is uprooted for 20 years before they can return home safely or find refuge elsewhere.)

This matters in and of itself. These lives are being blighted by abuse and neglect. And while humanitarian need is the product of political crisis, unmet humanitarian need is a cause of political instability. Just listen to Jordan’s King Abdullah, who told the BBC last year that his countrymen were at “boiling point.” (As of February, there were 633,000 UNHCR-registered refugees in Jordan.)

The problem is manageable, not insoluble. Cash support for refugees, rather than food or tents, gives them power and boosts the local economy. Education accounts for less than 2% of the global humanitarian budget, which makes no sense given the duration of displacement.

Refugees need to be able to work, as they can in countries like Uganda, and for that to be possible the countries hosting them need the kind of support that was offered to European countries recovering from war and benefiting from the Marshall Plan 70 years ago.

And for the most vulnerable refugees (for example families with medical needs), resettlement into the Western world is a priority. The numbers will not go beyond the hundreds of thousands, but the new start for them is life saving and the symbolism for the countries hosting refugees huge.

The crackdown on refugees by the Trump administration is neither good policy nor good policy-making. These people are victims of terror, not terrorists – and in any case, it is harder to get to the US as a refugee than through any other route.

So this is a world where thresholds are being broken or redefined every day, and rightly so. But some really do matter and they must be respected and upheld.