Editor’s Note: Keeping you in the know, Culture Queue is an ongoing series of recommendations for timely books to read, films to watch and podcasts and music to listen to.

The campaign by American photographer Nan Goldin to shame galleries and museums into cutting ties with the Sackler families, the owners of OxyContin manufacturer Purdue Pharma, was always under a lens — that was part of its point. Beginning in 2018, a number of noisy protests at some of the art world’s finest institutions, including the Met, the Guggenheim and the Louvre, were designed to attract as much publicity as possible as they highlighted the horrors of the United States’ opioid epidemic and called out Purdue Pharma’s role in it. They proved highly effective.

Among those documenting the protests was Goldin herself, working with the activist group she cofounded called P.A.I.N (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now). Knowing the artist wanted to create a film about what they were doing, the group filmed with producer-friends for months until Goldin met Laura Poitras, an Oscar-winning director who would make it a reality.

In that way, Poitras’ now Oscar-nominated documentary, “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed,” began in the hands of its subject — and much like one of Goldin’s own artworks, it ended up in a very different place from where it started.

To Poitras — whose 2015 Oscar-winning documentary “Citizenfour” explored how whistleblower Edward Snowden took on the US government over its surveillance practices — Goldin’s situation initially seemed like another David and Goliath story. The photographer says she had survived an addiction to OxyContin, which she’d started taking after a surgery in 2014, and was using her clout to call out what she saw as “artwashing” — or using cultural investments to distract from controversy — on the part of the Sacklers, who have previously denied wrongdoing related to the opioid crisis. But after Goldin began confiding in Poitras, the portrait of the artist changed; so did the story both would end up telling.

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed,” which became only the second documentary to ever win the Golden Lion for best film at the 2022 Venice Film Festival, and is also nominated for a BAFTA, begins in 2018. It follows Goldin’s successful campaign, which resulted in many prominent galleries refusing Sackler money, and the Met, the Louvre and others eventually purging the Sackler name from buildings. (After Purdue Pharma filed for bankruptcy in 2019, the company and the Sackler families reached a $6 billion opioid settlement with a group of states and the District of Columbia in 2022. As part of the deal, they agreed to allow any institution or organization nationwide to remove the Sackler name from facilities and academic, medical, and cultural programs, scholarships, and endowments, as long as the Sacklers were notified first and announcements regarding the name removal did not “disparage” the families.)

Entwined with that thread is a defiant and devastating retelling of the artist’s decades of activism and life among New York’s LGBTQ subculture. Then, there is the story of Goldin’s own family tragedy.

Cycle of misplaced stigma

Goldin is best known for her pioneering, taboo-busting photography slideshow series “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency.” Featuring the artist, her friends and countercultural figures of 1970s and ’80s New York, it’s a masterclass in curation that continues to evolve to this day. A slide goes in, a slide goes out; new images are pushed together, new harmonies and juxtapositions formed. The sequence evolves, and with it, the story she tells.

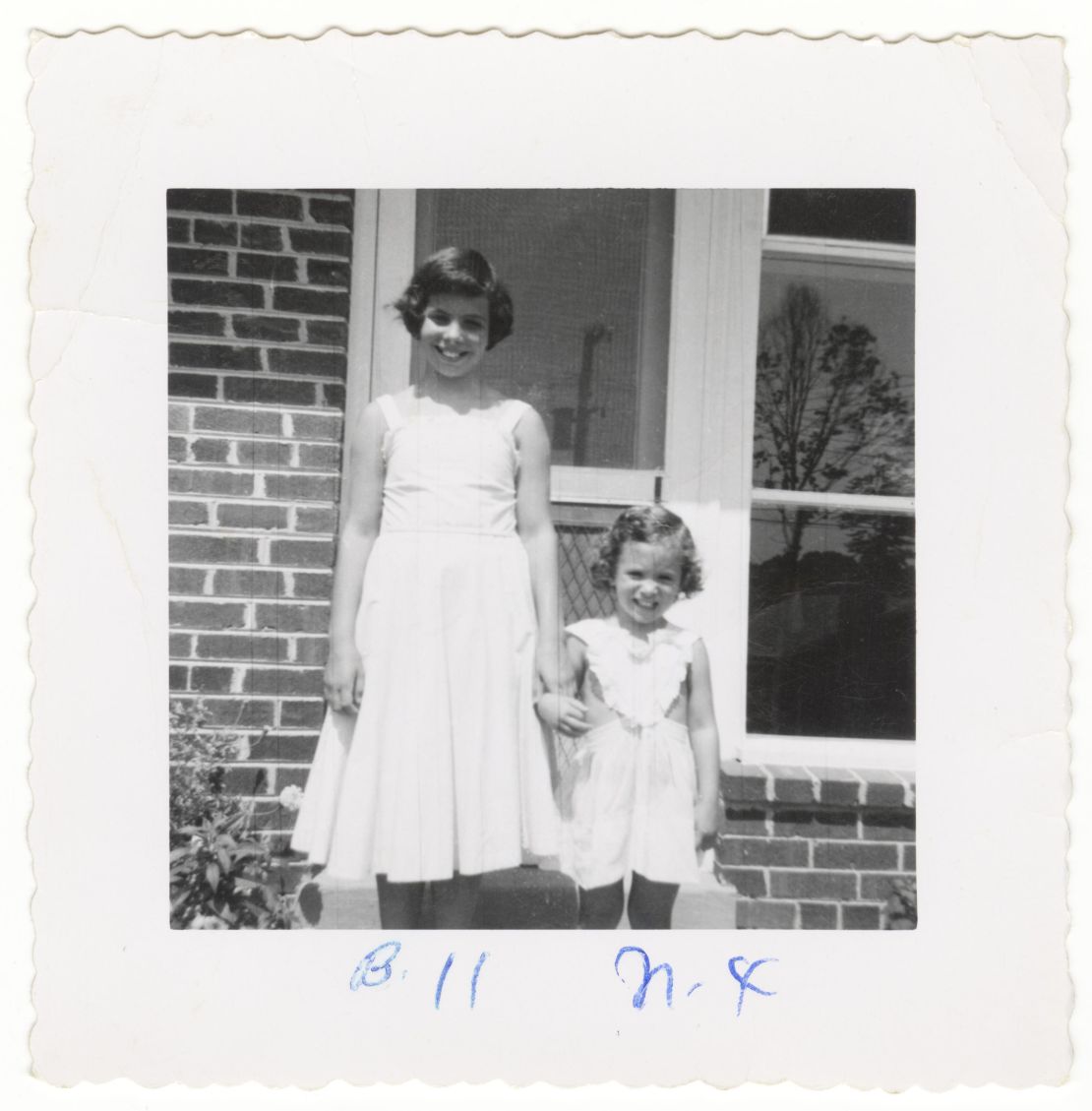

The notion of reconfiguration is one Poitras would embrace when she began to learn about Goldin’s older sister, Barbara, who ultimately became the film’s emotional throughline.

Barbara, who was attracted to women, was a “young woman who’s rebellious, who’s sexual, who is resisting the status quo, at a time where society didn’t accept that in the early ’60s,” Poitras said. She was labeled mentally ill and institutionalized, and died by suicide as a teenager. Her story, depicted in Goldin’s 2004 slideshow “Sisters, Saints and Sibyls,” left Poitras “wrecked,” but she felt including it in the documentary was “important to understand Nan’s work — and Nan agreed.” (Much of Goldin’s work, and Poitras’ film, is dedicated to Barbara.)

Poitras sat down with Goldin for a series of off-camera interviews during the making of the documentary. Goldin would bring along family photographs and request more interviews, inviting the director to dig deeper, Poitras remembered. The Sackler campaign may have been the “hook for me as a filmmaker,” said the director, but “what happened to (Barbara) I think is really the heart of the film.”

Spurned, shamed and denied her truth with terrible consequences, the stigmas that contributed to Barbara’s death are echoed in the HIV/AIDS crisis Goldin later witnessed and in the opioid epidemic that continues to rage. The cyclical nature of these generational calamities was reinforced by Goldin using “die-ins” — the signature tactic of HIV/AIDS activist group ACT UP in the late 1980s and ’90s — in her protests against the Sacklers.

Breaking that cycle of stigma has become a mission for Goldin; it’s why she decided to go on record to Poitras about her past sex work, experience as a survivor of domestic violence, OxyContin overdose and time in rehab. “The wrong things are kept private in society, and that destroys people,” the artist said in the film.

An uncompromising story

Even with such a candid subject, Poitras and her researchers kept digging.

“There’s a risk or danger with interviews where people have their narrative and they just sort of repeat it,” Poitras said. “I was trying to get away from the script.”

Researchers found bits of Goldin’s past that even she hadn’t seen, like rare 8mm film from Provincetown, Massachusetts, featuring the cult director John Waters and his muses, the actors Cookie Mueller and Divine, queer icons who were among Goldin’s friends. Poitras presented Goldin with the footage when they spoke.

“I was very focused on trying to make things present,” Poitras said. “I would try to look for things to help center into the past that I was interested in.”

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” weaves historical footage together with contemporary video and also features the artist’s photography archive, overlaid with audio from Goldin’s interviews. Goldin’s words offer fresh context to images that already spoke volumes — photos like “Nan one month after being battered” (1984) or those taken inside Tin Pan Alley, a bar staffed entirely by women in New York City’s Times Square. These throwbacks are neither gratuitous nor egotistical in Poitras’ hands; due to the cyclical themes the film explores, almost always, the past is in service of the present.

As artist-reporters, Poitras said she and Goldin share some of the same storytelling DNA (before she won an Oscar for her documentary about Snowden, Poitras was among the journalists whose reporting on the NSA whistleblower won a Pulitzer Prize in 2014).

“I think her eye in photography is at another level, but it allows me to be in places that I wouldn’t be otherwise. To sort of walk through fear and to have a voice,” the director said. “I do feel very, very aligned with what Nan talks about in terms of the camera as a way to get at truth — both emotional truth and historical truth.”

The tale of the opioid crisis as told by “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” is often raw and uncompromising. Even in the wake of the 2022 opioid settlement, the director remains vigilant.

“These are very powerful people, wealthy people who have an army of lawyers,” Poitras said. “We have certainly braced ourselves for those attacks and are prepared for them — and welcome them, should they choose to come after us.”

CNN reached out to representatives for several members of the Sackler families for comment and did not received a response prior to publication. Purdue Pharma responded to CNN’s request for comment on the documentary with a statement:

“We have the greatest sympathy and respect for those who have suffered as a result of the opioid crisis, and we are currently focused on concluding our bankruptcy so that urgently needed funds can flow to address the crisis,” it read, in part.

Poitras’ film was edited in collaboration with Goldin, with changes made even after its Venice premiere in September. The tweaks were all planned and budgeted for, given that both have a habit of tinkering, the director said. Should a fresh chapter in Goldin’s campaign emerge, could the film, like one of the artists’ slideshows, go back into edit?

“It’s locked,” Poitras said. “But anyway, don’t hold me to that. I can’t promise.”

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” opens in UK cinemas on January 27 and is in select US theaters now.

Add to queue: Tales of the opioid epidemic

View: “Kensington Blues”

Jeffrey Stockbridge’s photo series documents the inhabitants of Kensington Avenue in North Philadelphia over the course of five years. The city has one of the highest overdose rates in the US, and the street is in one of its poorest neighborhoods, awash with drugs and homelessness. Stockbridge’s lens has compassion for his subjects, but is unsparing in showing the depths of deprivation endured.

Read: “Empire of Pain” (2021)

What began as a 2017 article in The New Yorker became a bestselling book by journalist Patrick Radden Keefe (who also features in “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed”). Winner of the 2021 Baillie Gifford Prize for non-fiction, Radden Keefe walks readers through a history of the Sackler families, Purdue Pharma, and the company’s manufacturing and marketing of opioid OxyContin.

Read: “Cherry” (2018)

Nico Walker’s searing debut novel was adapted with mixed results into a film starring Tom Holland. Choose the book. Walker writes the gripping tale of a US Army veteran who returned from Iraq, developed an addiction — and became a bank robber to fund it. A work of warts-and-all autofiction, Walker wrote “Cherry” while in prison for robbing banks.

Watch: “Mare of Easttown” (2021)

This limited series by Brad Ingelsby aired on HBO (which is owned by CNN’s parent company, Warner Bros. Discovery) and starred Kate Winslet as a detective pursuing a murder investigation in a close-knit town. Opioid addiction isn’t the series’ chief concern, serving rather as a disquieting backdrop and fine example of how the crisis has permeated communities across the US.

Top image: “Nan in the bathroom with roommate,” Boston, 1970s (Photo courtesy of Nan Goldin)

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, domestic violence issues, substance abuse or other mental health matters, the following support is available:

— Suicide & Crisis Lifeline: Call or text 988. The Lifeline provides 24/7, free and confidential support for people in distress, prevention and crisis resources for you and your loved ones, and best practices for professionals in the United States.

— National Domestic Violence Hotline: Call 1-800-799-7233 or text LOVEIS to 22522 for 24/7 support.

— Domestic Substance Abuse and Mental Health Issues: The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), has a national helpline — 800-662-HELP (4357) — which provides free, confidential treatment referral and information in English and Spanish 24/7, every day of the year.