In the early hours of December 14, 2022, 39 migrants were saved from a collapsed rubber boat stranded in the middle of the English Channel between the United Kingdom and France.

Four people lost their lives in what was the deadliest such incident last year.

The UK government owns AI technology said to be capable of swiftly detecting these boats and even deploying life rafts. But it was a passing fishing crew that saved nearly everyone on board.

Special report

Britain’s shadowy border

A new army of drones, watchtowers and AI scours the UK coastline for small boats. But it didn’t stop migrants from dying

Published July 31, 2023

The Channel between the United Kingdom and France is one of the busiest waterways in the world. Hundreds of vessels from oil tankers and passenger ferries to small fishing boats transit through an area that at its narrowest is only 21 miles wide.

But in the past five years, as security tightened around rail and road crossings to the UK, the Channel has become a more common route for migrants desperate to seek asylum or a better life. It remains a perilous one.

Each year, thousands of people journey across the Channel in small boats, often made only of rubber, sometimes with fatal consequences.

As the numbers have increased year upon year, such crossings have become the focus of intense anti-migrant rhetoric. The UK’s Conservative government has set the tone, with successive home secretaries vowing to crack down on crossings and Prime Minister Rishi Sunak adopting the mantra “stop the boats.”

The digital border

The UK has invested millions of pounds in surveillance equipment as part of this campaign, ranging from drones to sentry — or watch — towers, all equipped with AI technology specifically designed to detect small rubber dinghies crossing the water.

While companies selling the technology tout its life-saving capabilities, the UK government has incorporated it into a campaign of deterrence, using the surveillance equipment to create an increasingly militarized border.

Flight path of a UK government drone

An AI-trained drone, provided by the Portuguese technology company Tekever, now flies across large swathes of the UK side of the Channel.

Each of these red points represents the position of the drone at a particular time between October 2019 and April 2023, the latest data available, with the lightest points being those where the drone was most frequently observed. The data indicates that the drone flew over French territorial waters on at least 35 separate occasions during this period.Source: OpenSky

Surveillance range of known AI sentry towers

Meanwhile, sentry towers with AI-trained cameras are now positioned on England’s south coast, each with a surveillance range of 15 kilometers (about 9 miles).

The locations, as identified by CNN, show Anduril sentry towers built along the British coast. The number of towers is not exhaustive as the UK Home Office has not disclosed how many it operates.Source: CNN

They were purchased by the UK government from Anduril Industries, an American tech startup that also built an AI system to monitor the United States-Mexico border.

But as the number of small boats arriving on UK shores continues to rise, it’s not clear whether this expensive AI technology is effective either in detecting the boats or in helping save the lives of those on board when they sink.

There are also questions over the government’s transparency in its deployment of AI technology along the coastline, with many Britons unaware this surveillance even exists.

The approach is part of a global trend in using AI technology to digitize border security. The Trump administration hired Anduril in 2020 to build a “virtual” border wall, pairing the president’s plans for a physical steel barrier with AI surveillance technology. Meanwhile, the European Union has plans to start deploying fingerprint and facial recognition software at its borders, developing “emotion detection technologies” that they say will act as an automated lie detector.

While the technology is embraced by governments, those working with refugees don’t believe it will deter those desperate to seek asylum and argue its use threatens their lawful right to do so.

“The rhetoric is ‘migrants are criminals, they must be controlled,’” Petra Molnar, a human rights lawyer and migration expert who is currently writing a book on AI surveillance and border security, told CNN.

“Technology could very easily be used for search and rescue, for finding boats faster and for preventing these horrific disasters. But unfortunately the reality on the ground is the opposite. It’s assisting powerful actors to be able to sharpen their borders and make it more difficult for people to come.”

Winter tragedy

Despite all the surveillance equipment, people have still lost their lives attempting to cross the Channel. CNN took an in-depth look at how the incident on December 14 unfolded, drawing on flight and ship-tracking data, official records from the French and UK authorities, a distress call from the vessel and interviews with a fisherman at the scene.

1:53 a.m. UK time.

A distress signal from the small boat is sent via WhatsApp voice message to a French charity, Utopia 56, which advises migrants to contact them if they cannot get through to officials. Utopia 56 later passes the boat’s position to the French and UK authorities along with contact details for those on board.

Distress call

Audio transcript:

“Hello brother we are in a boat and we have a problem please help. Uh, we have children and family in a boat. And a boat, water coming … we don’t have anything for rescue for … safety. Please help me bro please please. We are in the water we have a family.”

Hello brother we are in a boat and we have a problem please help. Uh, we have children and family in a boat. And a boat, water coming … we don’t have anything for rescue for … safety. Please help me bro please please. We are in the water we have a family.

In the pitch-black night with near-freezing air temperatures, the small rubber boat is crammed with dozens of migrants heading to the UK. As is typical of mid-December, the sea is rough and the winds strong. Approaching the middle of the Channel, the vessel begins to sink.

Among those on board are two Afghan boys, 12 and 13 years old.

Between 2:05 a.m. and 2:30 a.m.

French officials say the vessel is not detectable on shipping radar but ask two fishing boats and a commercial vessel in the vicinity to keep eyes on the small boat. The UK Coastguard says it plans to send a lifeboat to rescue the migrants.

2:45 a.m.

Ray Strachan, who was aboard a third fishing vessel in the area, hears screams from people in the water before spotting them.

“There was a lot of screaming and shouting,” Strachan recalls. “When they see us, they start swimming towards us, a lot of them with no lifejackets, it was unbelievable.”

There were multiple people in the water all around my boat.

Strachan calls the UK Coastguard, believing he is the first to alert them about the boat, and his crew begins hauling people out.

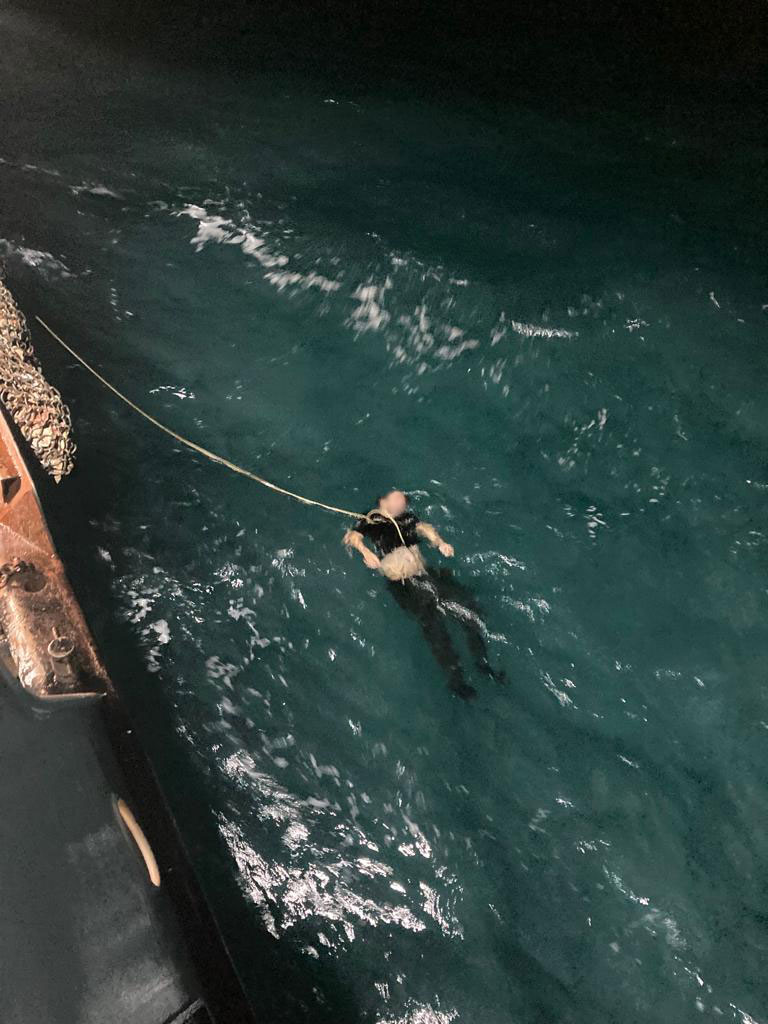

It’s difficult work as their clothes are sodden and heavy. The crew are exhausted and discover, with horror, that one man died after having attached himself to the fishing ropes in desperation.

His body surfaces as the boat starts motoring away. “He tied himself to the boat and we never knew he was there,” Strachan says.

Warning: This image shows a person who is deceased.

2:52 a.m.

Strachan and his crew rescue 27 people in the first hour and 31 in total.

“It’s not an area we fish in a lot, and if we weren’t there, everyone there would have probably drowned,” Strachan, who has been a fisherman for 39 years, says.

3:20 a.m.

When the UK authorities arrive, they rescue eight more from the vessel. Four people are later confirmed dead.

A 19-year-old has been charged with four counts of manslaughter and one count of facilitating attempted illegal entry into the UK for allegedly driving the boat. He has pleaded not guilty and the court case continues. Others on board now remain at detention centres in the UK.

Images from the night of the rescue show people being hauled out of the water using ropes attached to the fishing boat. A British RNLI lifeboat is the first official responder on the scene and drops a string of life rings to assist people. Credit: Ray Strachan

Where was the tech?

CNN obtained publicly available automatic identification system (AIS) data from MarineTraffic, a public ship-tracking platform, to better understand how the rescue operation unfolded in the early hours of December 14.

1:53 a.m. UK time.

The boat sends out a distress call while still in French territorial waters saying it is taking on water.

2:45 a.m.

Approximately an hour later the small boat is within UK waters. Strachan’s fishing vessel is visible arriving at the scene, finding multiple people in the water.

3:20 a.m.

A British RNLI (Royal National Lifeboat Institution) vessel is the first official rescue team to arrive. Its crew quickly calls for backup, realizing the severity of the situation.

3:45 a.m.

A UK Coastguard helicopter flies to join the rescue operation. Morerescue boats also head towards the scene.

A Tekever AR5 drone, used by the UK Home Office and capable of deploying a life raft, was operating in the Channel the day before the incident and in the hours after but not while the vessel was sinking, according to ADS-B data from Flightradar24.

Note: The location of the boat is not shown at this point, only the distress signal which was about 4 miles away.

In Freedom of Information requests to the UK Coastguard and Border Force, CNN asked whether Anduril and Sirius Insight cameras were in operation at the time or if they detected the boat, but the authorities declined to answer the question, saying they were legally exempted from providing the information.

In fact, a Tekever drone had flown over the same area where the distress call was made, despite being in French waters, in multiple previous voyages, according to ADS-B data from Flightradar24 and OpenSky. Tekever’s AI technology is also designed to spot even small vessels like the rubber dinghy that capsized on December 14. Such dinghies are not detectable on traditional shipping radar platforms.

According to Tekever’s website, the drones provide “real-time intelligence to make oceans safer and save more lives” and the AR5 drone has an “automatic identification system” able to detect vessels. Speaking on the company’s contract with the Home Office, Paul Webb, chief operating officer of Tekever, said it showed “our continued commitment to protecting and preserving human life through AI-driven drone surveillance.”

However, in some cases, drone footage has also been used by the UK authorities to identify those driving the small boats and prosecute them for human trafficking. In 2020, Rebwar Ahmed, an Iraqi man, pleaded guilty to a charge of assisting unlawful immigration after allegedly driving a boat with migrants on board and being shown footage from the journey. The Home Office said the surveillance footage “has been absolutely critical in securing convictions.”

Anduril Industries, which signed one contract with the UK Ministry of Defence for £3.8 million in 2021, and currently has a contract with the Home Office, uses AI-trained cameras that “autonomously detect” vessels at sea and then alert the authorities. Neither Anduril nor the UK government would confirm any information regarding the scope and value of their current contract.

Meanwhile Sirius Insight AI, which touts the details of its work with the Home Office on its website, told CNN its technology “can provide instant autonomous alerts” on targets it is tracking, while its cameras can spot “a very small vessel at 10 miles with just a couple of people in it.” The Home Office does not appear to have published any record of its contract with Sirius Insight AI. Tekever confirmed to CNN its contract with the Home Office was renewed in February 2023 for three years.

The Home Office did not answer CNN’s questions as to why its response took so long to save lives given the extensive AI technology in its arsenal, but said its thoughts were with those affected by the incident. In response to a Freedom of Information request submitted by CNN to the UK Border Force, they said disclosing how this technology operates in the Channel might "aid the criminals seeking to facilitate these dangerous small boat crossings by informing organized criminal gangs about the UK Government's ISR (intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition, and reconnaissance) capability” and “increase the risk to life at sea.”

The UK Coastguard declined to comment citing ongoing legal proceedings concerning the December 14 incident but confirmed that it and the Home Office do have multiple contracts with AI companies. Sirius Insight AI said it couldn’t comment on how the Home Office was using its equipment or on incidents where people had died in the Channel “because of the commercial nature of our relationship with the Home Office.” Tekever and Anduril said they were unable to comment on the matter and referred CNN to the Home Office.

CNN also sought comment from the French authorities regarding their role in the search and rescue operation on December 14 but has not received a response.

The effect on UK migration

Sunak has already hailed the “stop the boats” policy — one of five key pledges he announced in January — a success. But the numbers have in fact continued to increase dramatically, with nearly 4,000 people making the journey in June 2023, according to the Home Office, a record high compared to previous years.

Number of people detected arriving in the UK via small boats, June 2018 to June 2023

On July 17, 2023, the British government passed new legislation that criminalizes all those who seek asylum in the UK without prior authorization, like many who board these boats. The Illegal Migration Bill faced serious pushback in the British Parliament with the upper chamber, the House of Lords, seeking multiple amendments to the bill including adding safeguarding provisions for unaccompanied child migrants and modern slavery victims, but these were ultimately rejected and it was pushed through. The United Nations has slammed the decision as being at odds with the UK’s obligations under international human rights and refugee law, saying the bill will have “profound consequences for people in need of international protection.”

Meanwhile, the Court of Appeal, one of the highest courts in the UK, recently ruled that the government’s policy of deporting asylum seekers to Rwanda was unlawful, as Rwanda could not be considered a safe third country to receive refugees. The UK government has said it intends to appeal.

Molnar, the migration expert, says that evidence from the US and Europe indicates that governments’ focus on deterrence and surveillance is ineffective in preventing people from coming, many of them fleeing ongoing conflicts or environmental degradation.

“We've kind of lost the plot on what is really going on,” says Molnar.

“There is an internationally protected refugee law regime that allows people to claim asylum when they arrive on territory, and they should have access to a fair judicial system in order to be able to do so. But when we're weaponizing borders through technology, and preventing people from coming, what we're going to be seeing is increasing loss of life on the high seas.”

Correction: Because of an editing error, a previous version of this article referred incorrectly to the UK Coastguard and Border Force as companies rather than authorities when attributing their responses to CNN’s Freedom of Information requests.

Methodology

For this investigation CNN collected data on the AR5 drone, owned by Tekever and licensed by the UK Home Office. Its full flight history was taken from OpenSky, a public flight-tracking site. The flight data ranged from Oct 16, 2019 to July 13, 2023 and revealed the drone had flown in British and French territorial waters. CNN also examined the drone’s flight data using flight tracking sites ADSB Exchange and Flightradar24 which revealed it had flown between 10:00 GMT - 13:45 GMT on December 13, 2022, and 09:01 GMT - 13:49 GMT December 14, 2022 but not during the early hours of December 14, 2022, when the small boat carrying dozens of migrants was in distress. The Home Office also has access to an AR3 Tekever drone and two Anduril ghost drones; however, CNN was unable to collect data on these.

CNN submitted Freedom of Information Requests to the UK Home Office and UK Maritime and Coastguard Agency regarding which AI technology was used for the December 14, 2022 incident but the information was not disclosed citing ongoing legal proceedings and the use of equipment being a matter of UK national security.

To study the rescue operation on December 14, 2022, CNN used flight tracking data from OpenSky, ADSB Exchange and Flightradar24 to establish when the UK Coastguard helicopters arrived. MarineTraffic, a public marine traffic site, provided CNN with data for all vessels in the English Channel between 13:00 GMT on December 13, 2022 and 09:00 GMT on December 14, 2022, which revealed when Ray Strachan’s fishing boat arrived and when the UK lifeboats and other official vessels arrived. The location of the sinking vessel was established based on the location of Strachan’s fishing vessel at 3:00 GMT when, Strachan told CNN, it attached itself to the migrant vessel to haul people out.

Locations of Anduril surveillance sentry towers were established after speaking to two individuals living near an Anduril sentry tower. They provided imagery of this tower to CNN which was then used to identify further sentry towers along the coastline using Google Earth imagery. Their range of about 15 kilometers (about 9 miles) is based on information from the Anduril website. This list of sentry towers is not exhaustive. CNN reached out to the UK Home Office for a full list of the sentry towers and their locations, but this information was not provided, nor does it appear to be listed publicly.