Having survived an avalanche and been tested in some of the most remote places on earth, Jimmy Chin knows what it’s like to be at the mercy of mother nature.

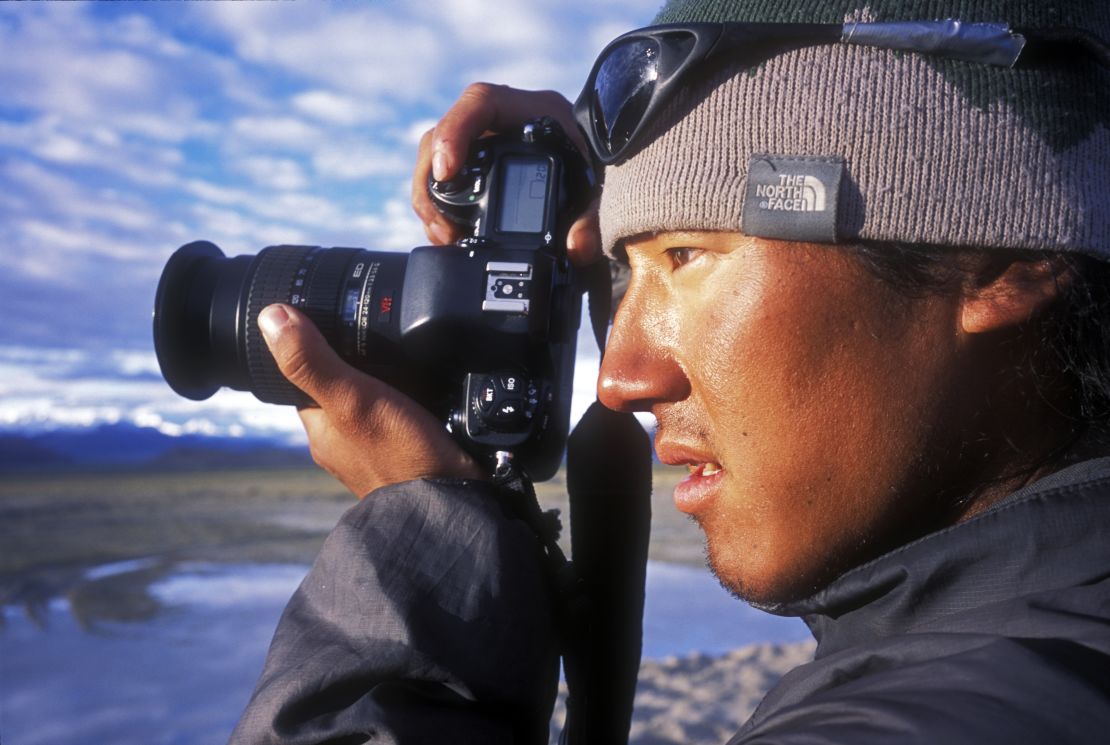

The renowned adventurer and filmmaker has spent the past 20 years traveling the world, pushing himself to conquer one historic challenge after another, and engaging in the sort of daring activities that would be beyond many people’s imaginations.

Whether it’s climbing Everest or filming the Oscar-winning Free Solo, the 46-year-old has captured the full extent of human endeavor.

“When you’re pushing for cutting-edge expeditions, you’re often in close proximity to potential disaster,” he told CNN Sport. “You’re constantly managing risk and you’re in fairly serious situations all the time, so your senses are very sharpened.”

But Chin’s intrepid way of life has been put on hold as the world comes to grips with the coronavirus pandemic. To a certain degree, his past expeditions have readied him for such uncertain times and, he said, he hoped others could learn from his experiences.

“This is a moment to pause, reevaluate and think about what’s important,” he added.

READ: ‘If he slips, he falls. If he falls, he dies’ – Climbing 3,000 feet without ropes

Early years

As a film director and National Geographic photographer, Chin has assembled a world-class portfolio of work. This year he returned from a trip to Antarctica, where he and a team of adventurers skied two new routes down the tallest and second-tallest peaks on the continent.

But such a life wasn’t always the plan.

As a child growing up in rural Minnesota, Chin was encouraged to pursue more traditional aspirations: excelling academically, as well as in martial arts and as a competitive swimmer.

But it was skiing on a small hill behind his house that he found freedom. “If I did well in everything else, I got to ski,” he said.

Already with a taste for the world of outdoor sports, Chin was introduced to climbing at college. At that point, he said, it was game over as the sport became a vehicle to see the world and explore places that made his “heart sing.”

He moved to Yosemite National Park where he worked odd jobs to fund his nomadic lifestyle, eventually picking up a camera and starting to shoot.

“I have so many incredible photographer friends who had a really noble vision for being an artist with their photography,” he laughed.

“But my whole entry into it was just ‘if I take these photos and I sell them I can make a little money so I can keep climbing.’”

READ: Like ‘falling off the face of the earth,’ says kayaker after dropping down 134-foot waterfall

Capturing the impossible

Since he himself is a professional climber, Chin’s photography services have been that much more in demand over the years, with the relationship between him and his subjects an important element of his success.

“If they’re going to be doing this thing, and you’re the only one documenting, they’ve got to trust that you’re going to get it,” he said. “Then I have to trust that the athlete isn’t just doing it for the camera.”

Such a collaboration was put to the ultimate test in perhaps his finest, and most daring, work to date.

Alongside his wife Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi, Chin documented Alex Honnold’s astonishing free solo climb up El Capitan in 2017.

Chin assembled a team of world-class climbers to help film Honnold ascend the 3,200-foot vertical rock face without a single safety rope.

Working together, they plotted where the cameras would be positioned on the wall so as to not distract Honnold on the day.

The historic feat won the team an Academy Award for Best Documentary at a ceremony that will live long in Chin’s memory.

“My confidence in Alex [Honnold] and his capacity to execute was very, very high,” said Chin, who had known Honnold for around 10 years before his death-defying ascent.

“I had seen him in very difficult situations before, completely unfazed, and I also knew that he’s the most calculated person I know. He’s not going to go do it if he’s not ready.”

Dealing with fear

Despite his years of experience, Chin said watching his friend train for and complete the climb was an ordeal.

“The fear was less acute than I think people might have perceived; it was more of a long-term dread,” he said, now able to laugh at the thought.

“I felt like it was on my shoulders for almost three years, from when we conceived of the project to filming it with him.

“Every day, whether he was free-soloing or not, there’s a potential for somebody to get hurt or die because you’re in these environments.”

Dealing with uncertainty is an occupational hazard for Chin and although meticulous planning can help iron out some of the danger, managing fear itself is essential to coping with the unexpected. Remaining calm, avoiding emotional decisions, can often be the difference between life and death.

“You have [to] step outside of yourself and be objective about a situation and make very objective decisions,” he said.

READ: Swiss climbs 1,800-foot rock face in record time… without a safety rope

Lockdown lessons

Though still working at home on a number of projects, it has taken a once-in-a-century event like the global pandemic to finally slow Chin down. He is now at least able to enjoy time with his young family.

“I’m just out in the yard playing with the kids, usually a rarity for me,” he said, acknowledging these were the most consecutive days he’d spent with his four-and six-year-old children.

“I don’t get that much time to hang out with them so I’ve been running around the yard and having fun.”

Living in a rural area means Chin is able to leave his house while still abiding by social distancing guidelines, a must for someone whose mental and physical well-being is “tied” to going into the wilderness.

He is a man who, in more ordinary times, usually searches for solitude, reveling in having time to think and ask existential questions. “It’s good to think about them,” he said.

It is not the sort of life many would choose, Chin admitted, but he hoped people in lockdown could learn from his experiences.

“Those are the kinds of experiences that I go and seek and now there’s an opportunity for people to do that. Take this moment.”